Getting to the Heart of the Matterings

My first encounter with the work of Ann Hamilton occurred last autumn when Paulette Gagnon, Head Curator at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, sent along several colour-Xeroxed photos of the 1997 Lyon incarnation of Hamilton’s installation “mattering” to accompany a catalogue essay I was to translate into English. While those few fleeting images of the work intrigued me and Ms. Gagnon’s text absorbed me (especially as I laboured to render her incisive prose into intelligible English), it was not until I received a copy of the published exhibition catalogue, with its ample and lyrical photographic documentation, that my initial curiosity developed into a fully fledged yearning to see the exhibit. So you’ll forgive me the fact that, despite having translated the catalogue text, I jumped at the chance of both seeing—or rather, experiencing—and writing about the exhibition.

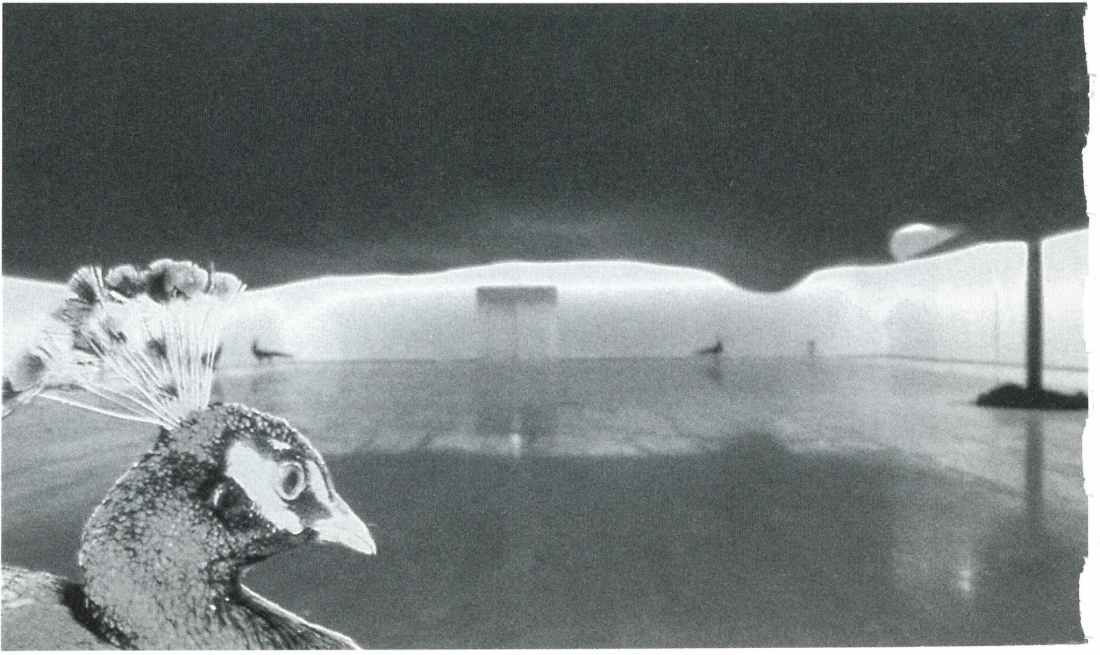

The exhibition itself was two-fold: “the body and the object: 1984-1997,” a compendium of 43 of Ms. Hamilton’s videos, book-works, installations, photography, constructions and sculpture (and in many instances an assemblage of all the aforementioned) which was originally organized by Ohio State University’s Wexner Center for the Arts, and “mattering,” an installation incorporating 500 square metres of orange silk vellum, a performer, countless yards of ink ribbon, a looming wooden column with perch, voice elements and five live peacocks which circulate freely about the floor. While both parts of the exhibition were inextricably linked, the boundless range and scope of the works exact that I confine my remarks to the “mattering” segment.

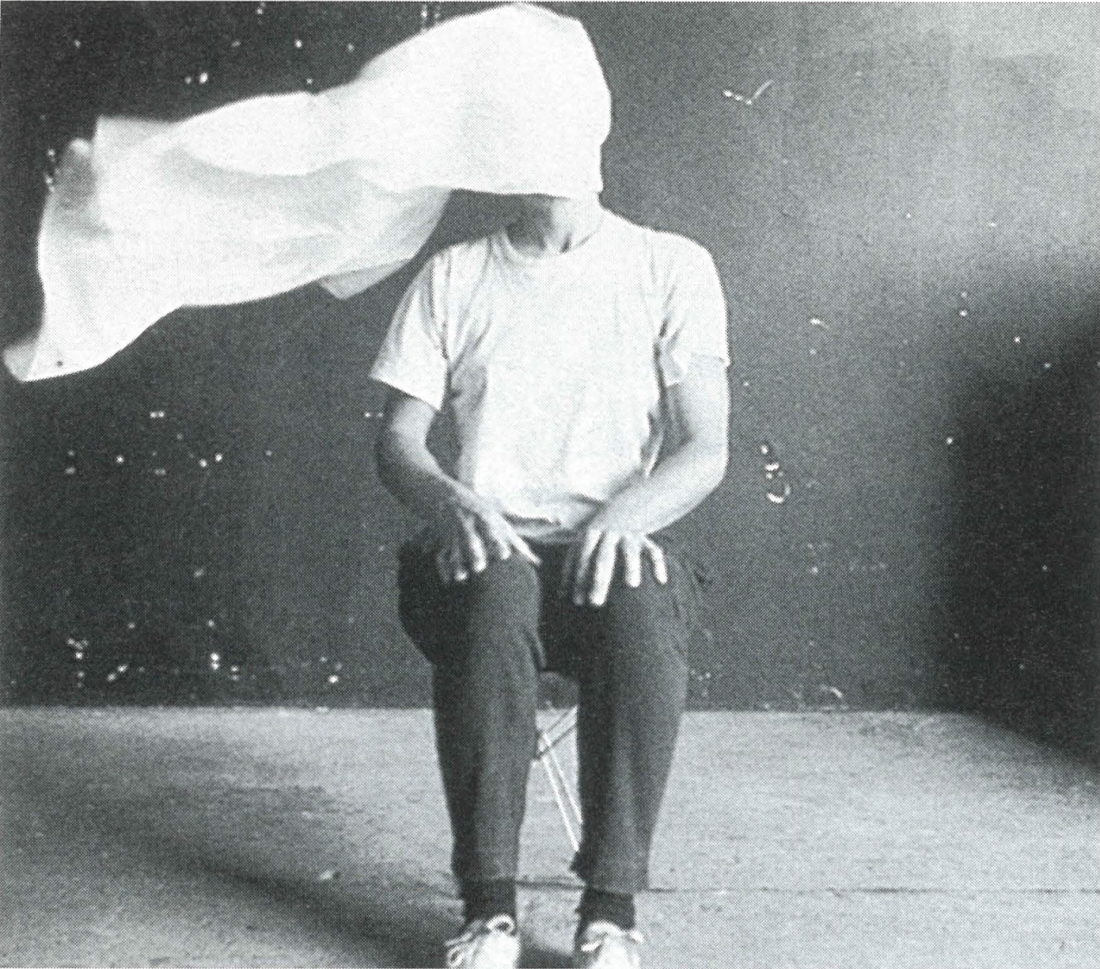

Ann Hamilton, Untitled (body object series) #4, 1985, silver gelatin print, 4 3/8 x 4 3/8”. Photographs courtesy Musée d’art contemporain, Montreal.

Entering the space, I was immediately enshrouded in an eerily soothing, deep-orange light which filtered through the vast swath of silk undulating overhead; this action was effected by means of cables attached to the material’s extremities and connected to a mechanism which wound and unwound at regular intervals. To quote Paulette Gagnon’s accompanying text: “The orange silk, like the hair in an earlier Hamilton work entitled tropos, 1993, creates a plane which stops at the perimeter of the room but which implies an extension beyond the architectural borders, endowing it with, according to the artist, ‘an oceanic sense’.” To one side of the great hall, there was a circular perforation in the fabric through which, as well as along the edges of the material, an intense light poured into the space like honey. A massive wooden column, spiked with ladder-rungs like so many thorns, ascended through the aperture into the atmosphere above as if to, in the words of the poet Michael Harris, “stir the idle heavens with our masts.” Atop that mast sat a performer who slowly, deliberately wrapped an inked ribbon (which appeared to be anchored to the depths of some lower level beneath the physical floor) around one hand. The barely audible sounds of vocal exercises intermittently wafted through the space while five peacocks meandered about, intermingling with spectators and behaving, not nearly as vaingloriously as their reputation would warrant. (As I viewed the installation in the company of my son, I was somewhat apprehensive that his encounter with the peacocks would result in a stampede and a 5-year-old fist full of exotic plumage. But my fears were unfounded; referring to them in flawless Brooklynese as “bew-tea-full toykeys,” he was content to follow them around aimlessly.)

The overall effect of these disparate elements was that they combined to at once disorient and relocate us, to defy and refocus the gaze. According to the artist, in her work, fabric has “an explicit presence.” It has been used to memorialize and honour absence of the human body (still life, indigo blue and lumen). While our perception below was refracted by this hallucinatory dislocation and the figure in the upper reaches went on with his work as if bandaging some unseen wound, his activity was at all times grounded to the rest of the piece by the haltingly rising ribbon. Ann Hamilton has written of this repetitive action that:

Ann Hamilton, Mattering, 1997, undulating silk, peacocks, voice, typewriter ribbon.

the deliberate process where the ribbon is first wound under and over each finger as a reference to weaving and spinning. The fingers are the warp—the vertical threads in the structure of the fabric—the inked ribbon is the weft. What is important here is the connection of that activity to the body… but more importantly, the twining of it to language production. The blue ribbon does transform within the activity of the gesture. So much ribbon accumulates on the hand that it becomes like a ball… when removed, the interior of the ball holds the shape of the exterior of the hand… The form memory of the typewriter ribbon springs back and the labor of the accumulation is absorbed… The transformation is several fold—exterior becomes interior—ink becomes mass—language to material—etc.

So what is at the heart of the matter is language, the aggregate elements or syllables that form an utterance. Or, for that matter, a form.

Matter is defined as the constituent material of which an object is made. But it is also contrasted to form, in that it is the component of the essence of any object which exists but which requires a particular ‘form’ to constitute it as being extant. It can also be subject-matter and it is in the semantic plurality of the exhibition’s title that Ann Hamilton’s “mattering” attains its arresting power and grace. Again, to quote Paulette Gagnon’s catalogue text:

The artist analytically explores the interwoven links between site, object, voice and gesture; at the heart of her preoccupations lies the notion of presence and absence. […] In their displacement of body to object, pretext to an unobstructed meditation, Ann Hamilton unveils a measure of the sumptuous materiality and immateriality of an ambivalent world. This deeply personal investiture of the components of her work signals a unique contribution to the history of contemporary installation. ♦

Ann Hamilton’s exhibitions “the body and the object: 1984 to 1997” and “mattering” were at the Musée d’art contemporain from October 9, 1998 to January 17, 1999.

Robert McGee is a Canadian freelance poet, translator and critic who lives in Brooklyn.