Gerald Ferguson

For near 40 years, Gerald Ferguson has made painting the subject of his art. His recent exhibitions pose the question: Is he now ready to make painting the object of his art? Ferguson has served as painting’s most vocal, strenuous and acrid leader of the loyal opposition. His open disavowal of the trappings of the painter’s craft and disdain for painterly excess have led him to turn away from the pleasures of paint and seductions of its history. His clarion call of the late ’60s decried that advanced art (at that time synonymous with painting) was in urgent need of reform. As respite, he turned his attention to stretch the boundaries of art making through his seminal contributions to artist’s books, sound works, performances and sculpture. Initially, his 2-D works were made on ephemeral scraps of butcher’s paper, brown rolled paper, foolscap, graph paper pinned directly to the wall, rebuffing artist’s paper, mat boards, frames, canvas and linen. His preferred mark-making implements were an HB pencil, felt-nib pen or a typewriter.

If he had made nothing subsequent to these groundbreaking works, his position as a pioneer of conceptualism and post-conceptualism would be assured. Yet, anyone remotely familiar with the sum total of his production would note the irony: Ferguson, the grand skeptic of object making, has been responsible for an astonishing outpouring of, well, dare I say it, “paintings.”

Gerald Ferguson, Four Ash Cans, 2006, acrylic enamel on linen, 48 x 48”. Collection: Dalhousie Art Gallery. Photo: Steve Farmer.

He supplemented his ’60s procedural, task-oriented art, adding masking tape and spray paint to his repertoire. While he may once have used the back end of the brush to effect a little sgraffito, he seems blissfully unaware that the majority of painters use the hairy end. Corner bead, urinal drain covers and pegboard-like materials were employed as his homegrown version of Duchampian standard stoppages. Ferguson used them as templates to stencil the grids that structured his late ’60s and ’70s “dot” paintings on unprimed, raw canvas. Beauty by the back door and expressive painterly flair, generated courtesy of the fortuitous by-products of overspray, misalignment and inadvertent scumbling. These lean, elegant post-minimal/ post-conceptualist works make it clear that a reductivist’s taste for Arte Povera does not by necessity result in “impoverished art.” Their audacious paucity and confident, refined restraint withstand comparison among the distinguished company of Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman and Sol LeWitt.

Thirty-eight years ago, Dalhousie Art Gallery mounted Ferguson’s first ever solo exhibition, to be followed by a reprise roughly every 10 years. His current show is the swan song for departing director Susan Gibson Garvey. It celebrates a gift to their collection of 17 marvellous paintings of 1994 to 2006, and unveils Ferguson’s new “Ash Can” series. Simultaneously, Gallery Page and Strange presented selections from the “Door Mat” works. Together, they permit us to view Ferguson’s preoccupations over the past decade, view them within the continuum of his development, as well as gauge where his work might lead in the future.

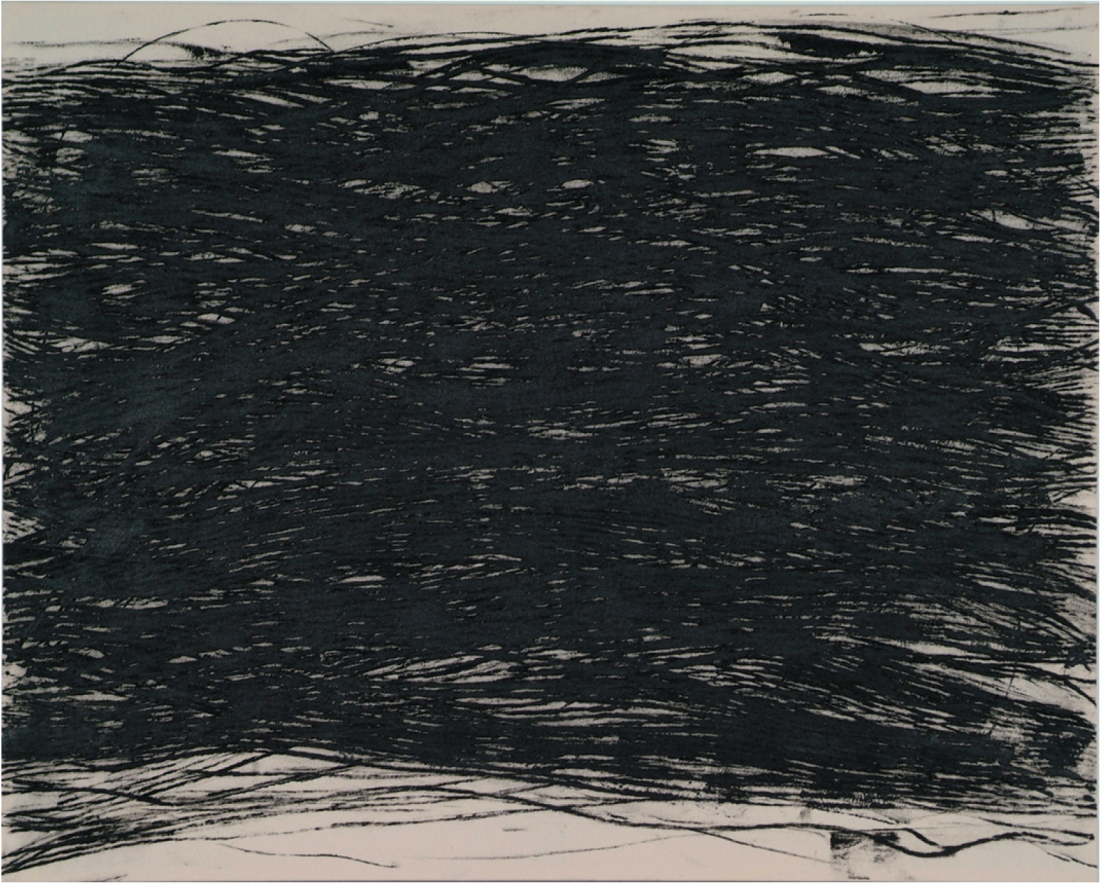

Gerald Ferguson, 550 Meters of Rope, 2000, acrylic enamel on canvas, 48 x 60”. Collection: Dalhousie Art Gallery. Photo: Steve Farmer. 42424text.

Overall, these works rely on the precedent of Max Ernst’s frottage (taking a rubbing/impression), which Ferguson notes “was an experiment designed to achieve the ‘marvelous’….” Ernst’s suite of surrealist prints, “Histoire Naturelle,” 1926, commences with pages of elemental textures that evolve into inchoate amoebic masses, then successively to vegetative, then animalistic, forms, reaching a crescendo with the appearance of a lone image representative of mankind. In Ferguson’s hands, frottage outlines “impressions on canvas using a house painting roller with paint passed over a variety of common objects.” He reverses Ernst’s process by starting with discernible source objects that devolve into pattern and mass. Ferguson’s The Artist’s Studio provides the most direct Ernst comparison. For Susan Gibson Garvey, “these are not actually abstract works,” but, instead, vestiges, traces of the source objects. Ferguson’s show presents key examples of each step and variant of his exhaustive, methodical exploration of the topic.

The elegant “Rod” pictures are near impossible to read in reproduction. Their qualities rely upon their rich tactility of evocative, dark, densely packed paint. Ferguson’s choice of house paint on raw canvas parallels Alberti’s moral preference for the use of white rather than gold in art. While Alberti believed this constraint elevated art, Ferguson gives the back of the hand to any inclination towards “Newman’s high spirituality.” No contemplation of lofty purpose, no wallowing in the glories of base material: no bliss, no bling.

The selection of hardware-bought items as source material—chains, ropes, laths and fencing—pays homage to his working-class roots. By happy coincidence, they simulate the patterns of recent art. The circle form of works such as 200 Meters of Hose he likens to a doughnut, rubber tire or a kitchen stove burner. Art aficionados could be excused if, instead, the drawings of Richard Serra came first to mind.

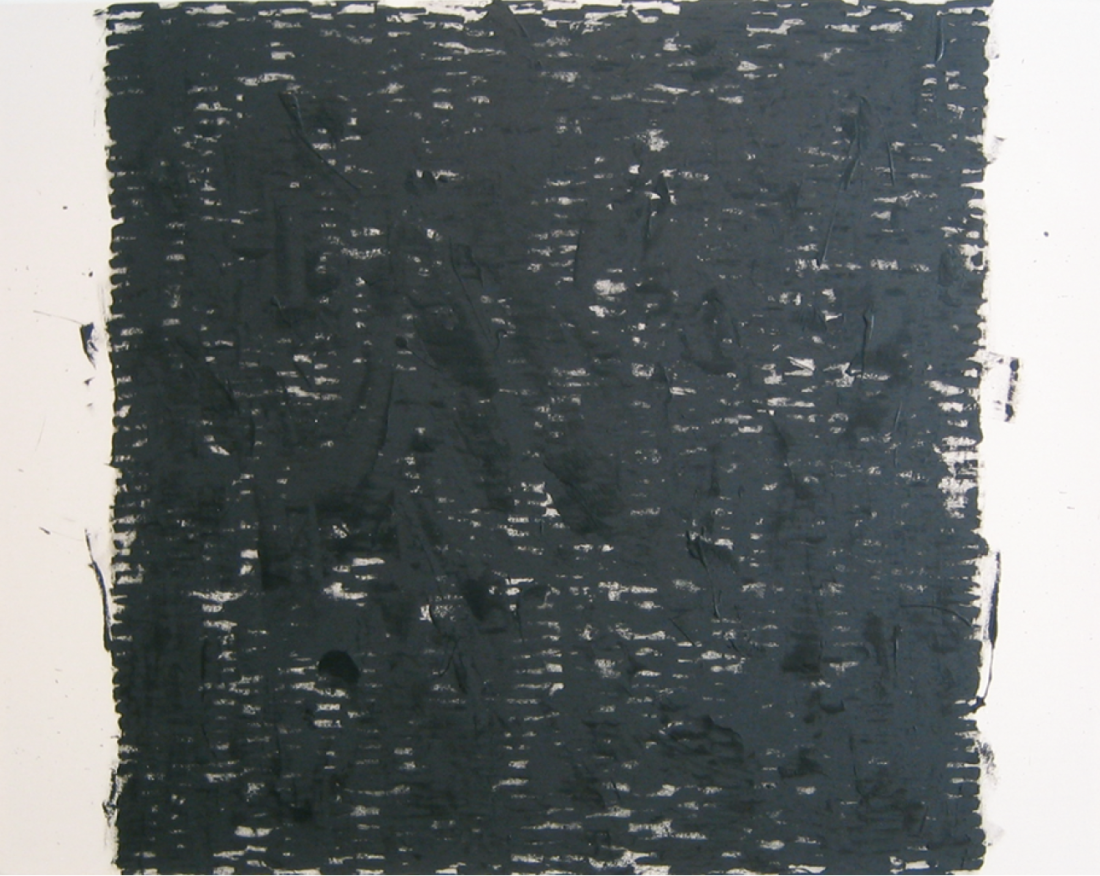

Installation: Gerald Ferguson, “Door Mat Paintings” at Gallery Page and Strange, Halifax, 2007.

Ferguson’s drop cloth paintings are drop dead gorgeous. Used (soiled) house painter’s drop cloths are gently nudged into art status by virtue of the addition of a quick pass of the roller over chains. I wonder if I would have appreciated their virtues if I were not previously schooled in the values of the ’70s figure-ground paintings of Jack Bush.

Ferguson has given us plenty to cheer about in these new shows. So why are the crowds so disconcertingly quiet? Could it be that just when we find ourselves enthralled by physically compelling passages, twists and turns, new explorations, we are sucked back down into the morass of the politics and polemics of taste? Ferguson can seemingly never set aside the temptation to demonstrate his ethical superiority. He footnotes his opposition, warning the viewer against the pitfalls that await those who transgress towards the pleasures of pure painting.

He reminds that we are obliged to view his work as an ironic critique of painting’s practice, ceding that a significant portion of the value, meaning and experience of his work is attributable to its deconstructive positioning. As Susan Gibson Garvey observes, he wishes to question painting’s authority, “yet retain its once unique role as the purveyor of meaning and beauty.” Perhaps presenting oneself as “painting’s defender of the faith” is an anachronistic miscue.

Trouble is, there are frightfully few souls left in Canada in genuine need of saving. We would be hard pressed to find a curator or art commentator in the country flirting with or willing to publicly espouse the virtues of high modernist painting. Greenbergian modernism collapsed and gave way to post-conceptualism, just as surely as communism fell to capitalism. To paraphrase a political analyst—“while it is true that the right side lost, it is also true that the wrong side won”—we’ve exchanged one dogmatic essentialist ideology for another.

Gerald Ferguson, Six Door Mats, 2006, enamel on canvas, 55 x 70”. Courtesy: Gallery Page and Strange, Halifax.

The current generation of Canadian curators has turned a blind eye to the machinations of painting and sculpture. Modernism isn’t exhibited, actively discussed, considered or even remembered, never mind avidly debated. Most don’t even care to form or express an opinion about what constitutes beauty or a proper path for new painting or sculpture. It is out of mind, not on the agenda. Art that chooses to make the critique of taste, judgment and painting its main thrust ought to be prepared for the worst; it will likely be assessed to be of marginal utility and have a limited shelf life. Within this context, Ferguson’s interminable haranguing of the fallen bastion of modernist painting is a tad ungracious and mean-spirited, not unlike kicking a dog that has already been run over by a truck.

Ferguson’s art, past and present, for my account, is among the best of our best. Certain cultural disappointments abound; let’s hope that, irrespective, he can remain “Close to the edge, but not going over the edge” upon the slippery slope that leads from door mats to bath mats to bathos. ■

Gerald Ferguson’s “Frottage Work 1994–2006 and Ash Can paintings 2006,” curated by Susan Gibson Garvey, was exhibited at the Dalhousie Art Gallery in Halifax from May 11 to June 30, 2007.

“Door Mat Paintings” was exhibited at Gallery Page and Strange in Halifax from April 27 to May 18, 2007.

Jeffrey Spalding is an artist and arts writer, and currently Director and Chief Curator of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.