George Steeves

Photographer George Steeves came to national attention in the mid-’80s when he exhibited his first body of work in the key of E. “Pictures of Ellen,” 1981–84, was an extended portrait of performance artist Ellen Pierce in all her guises as their collaboration-turned-love-affair bloomed, then imploded. Pierce is glorified in the languid déshabillé of sex-drenched morning; she is exposed in the cold light of Awful Morning, Marlborough St. The work emerged at one of those curious moments (more and more frequent, it seems) of political friendly fire: within what should have been an enabling art world, the series was vilified for perpetuating the villainy of the male gaze. The discourse around “Pictures of Ellen” was stillborn in this politics, but Steeves’s subsequent bodies of work are, in a very real sense, its children. These include “Edges,” 1979–89, in which Steeves paired non-silver, sometimes hand-painted urban landscapes with portraits of family, friends, lovers and himself (in hospital, after a suicide attempt); “Evidence,” 1981–88, a portrait of a marriage that Steeves was both observing and helping to destroy; “Exile,” 1987–90, an extended portrait of critic, poet and hedonist Astrid Brunner; “Equations,” 1986– 93, a theatre of identity erupting from the fertile imaginary of Steeves’s marriage to designer Susan Rome; “Ensemble-séparé,” 1997, a series of portraits turning on the subjects’ responses to a feather boa; “Elsa’s Kind,” 1991–98, subtitled “Exile Book II” as an extension and radicalization of the work with Brunner. Wives, lovers and soulmates have collaborated in these projects, each of which is revisited—indeed, honoured— in Steeves’s monumental self-portrait “Excavations.”

There are literally thousands of negatives that will eventually form the corpus “Excavations.” A solo exhibition selected by the artist from his work-in-progress has recently been organized by Ingrid Jenkner for Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery in Halifax. Seen in situ—in the city where most of the pictures were taken, where the virtuosic prints were made; in the very space where Steeves made his photographic debut—it heightens one’s awareness of the community that has formed visually and affectively around his work. Indeed, the organization of the work on the walls is oddly reminiscent of a photographic album. In its copiousness, reflexiveness and domesticity, the collection forms a life storybook that yearns, sometimes rages, for a compassionate telling.

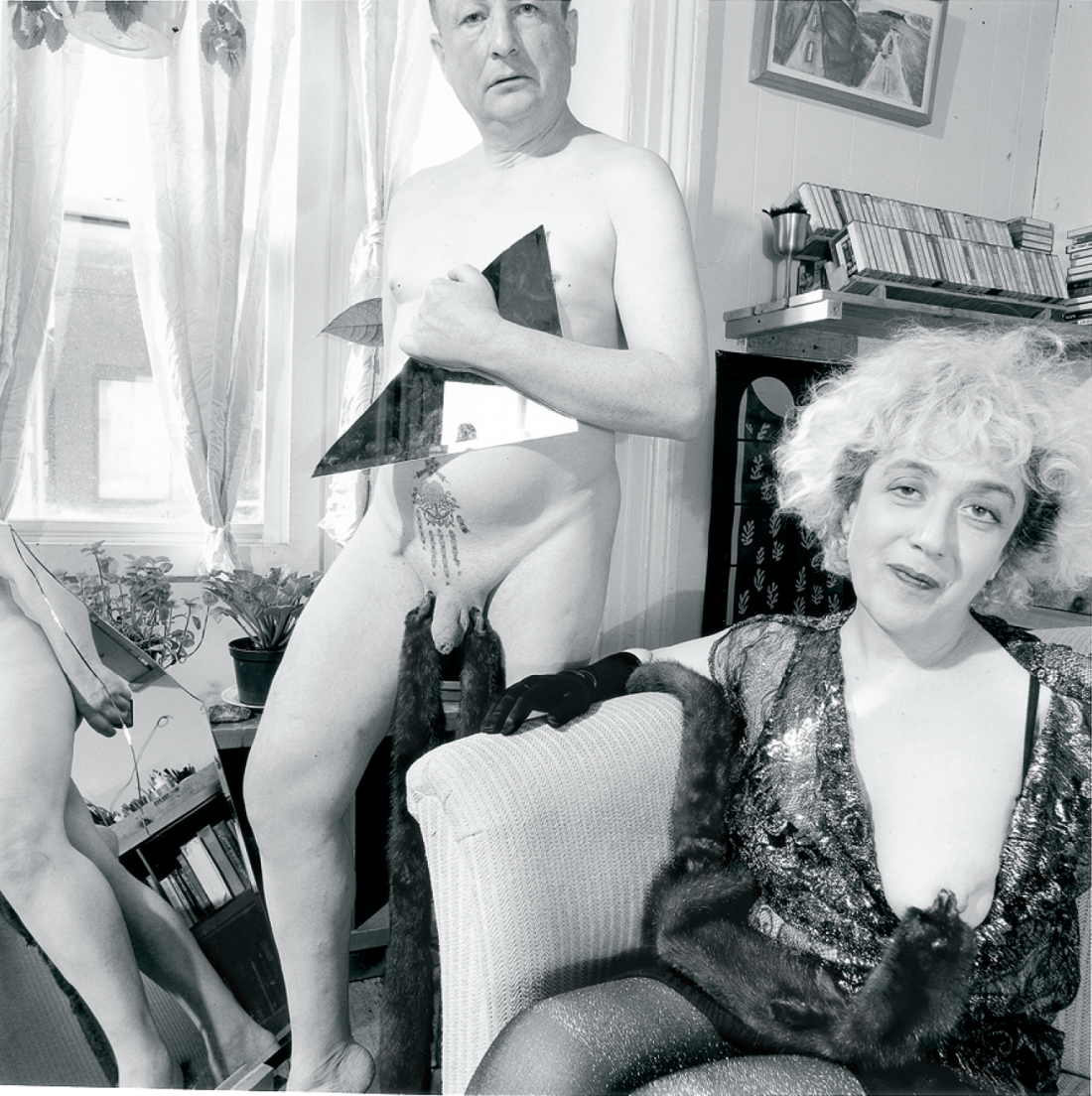

George Steeves, E-Minor No. 12 (GS & LH), 2001, all prints silver gelatin on warm-tone, fibre-based paper treated with selenium, 36.8 x 36.8 cm. Collection: the artist. Courtesy Mt. St. Vincent Art Gallery, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

I said “oddly”: the individual photographs resist the paradigm of family photography in a number of ways, the most obvious being their attention to the body, both its functions and display. In the first photograph of the first section, Steeves pictures himself pissing in the snow. This act is pictured, meaning that it is also figured as a performance for the camera. Steeves is, therefore, posing in a costume. He wears a dark suit— I mean that literally—just the coat and trousers, which are unzipped, revealing the white lining of this nicely constructed garment and bracketing his penis and scrotum. The body is thus exposed to my gaze, as to the cold, though it seems immune to both. The implacable expression and lassitude of the pose nullify the urgency of the pretext; one hand hangs relaxed at his side; the other is in his pocket, no doubt keeping company with the shutter release. In the next photograph, Astrid Brunner sits astride a toilet. She holds a glass, she smokes; she might be peeing, we don’t know—I am saying that even this minimal narrative (“I went to the toilet and … ”) is evacuated from the picture, which is really about (to the degree that it is about anything) the scaffolding of being on which we hang our survival. In Brunner’s case, as driven home by “Exile” and “Elsa’s Kind,” the construction is erected on physical and psychological scar tissue, on precious and delicate objects, such as crystal and jewellery, and, most crucially, on photographic opportunities that don’t promise to flatter the subject but actually do, assuming that she doesn’t give a shit about being glimpsed on the toilet, but rather knows how her huge breasts will be contoured by her little black dress, how her legs spread and tensioned by high heel shoes will display to advantage. There is nothing unusual in these calculations—on the contrary, these are the games that people play when they pose for the camera. Brunner’s performance inscribes her intellectual seriousness and sexual bravado; she scribbles on her walls; she sits where she can find a perch; she keeps a clean privy. Life is full of such richness, if you know where to look.

I am naming the figures; this first part, “Envoi (Exegesis),” is designed for me to do so, composed of characters who may face the camera or look away, but who are clearly engaged in a consensual photographic act. In 14 photographs, I meet many of the principals and, by the third photograph, I have begun to understand something of what essayist Peter Schwenger calls their “desiring.” Steeves poses with Liane Heller in a ramshackle urban setting. The remains of a porch, a screen of hedge and a cinderblock building construct their theatre. Steeves sits on the edge of the platform with Heller behind him: he reaches up with his left hand, which is cupped under her chin; she, full-faced in her giving to the camera, stretches out her arms and flies under photographic power.

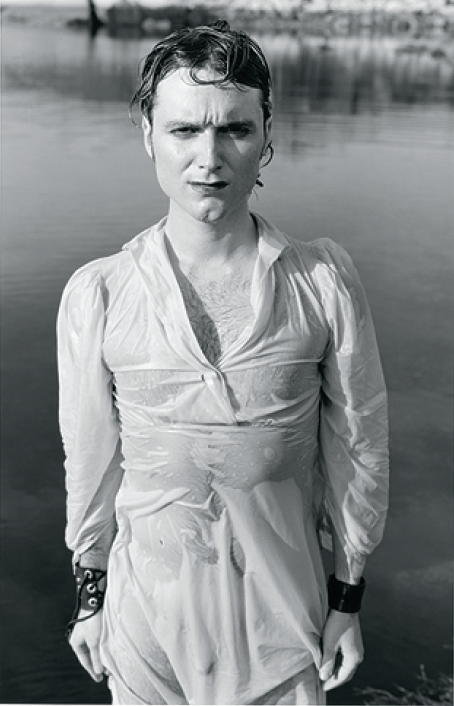

George Steeves, Exegesis No. 7 (GRS), 1996, 45.8 x 30.5 cm.

The second part, “Epiphany (Entropy),” reinstates gravity. Opening on a caged man, the section develops, image by image, drop by poisonous drop, a hopeless feeling of denial and restriction. The Heller who flew now presses her hands on a tablecloth, obsessively smoothing its wrinkles as her naked partner looms alongside. An excess of attributes weighs down on the characters— they are marked by their desires, fixated on their own reflections, bent over their own roiling guts. Here, the man met peeing in the snow is moved to take up arms. The curious thing is: where. He poses on a porch; it is, in fact, Steeves’s father’s home on Prince Edward Island, a portrait made as his father lay dying in hospital. That knowledge informs a biographical reading, if that is the course one wants to take. But the picture is arresting on sight because the pose is all wrong. The man (Steeves) is not guarding the house against evils in the world, he is guarding the world from the evils of the house. The interior shall not be allowed to pass to the exterior. This rule holds throughout the section; it is broken under the heading of “Extasis.”

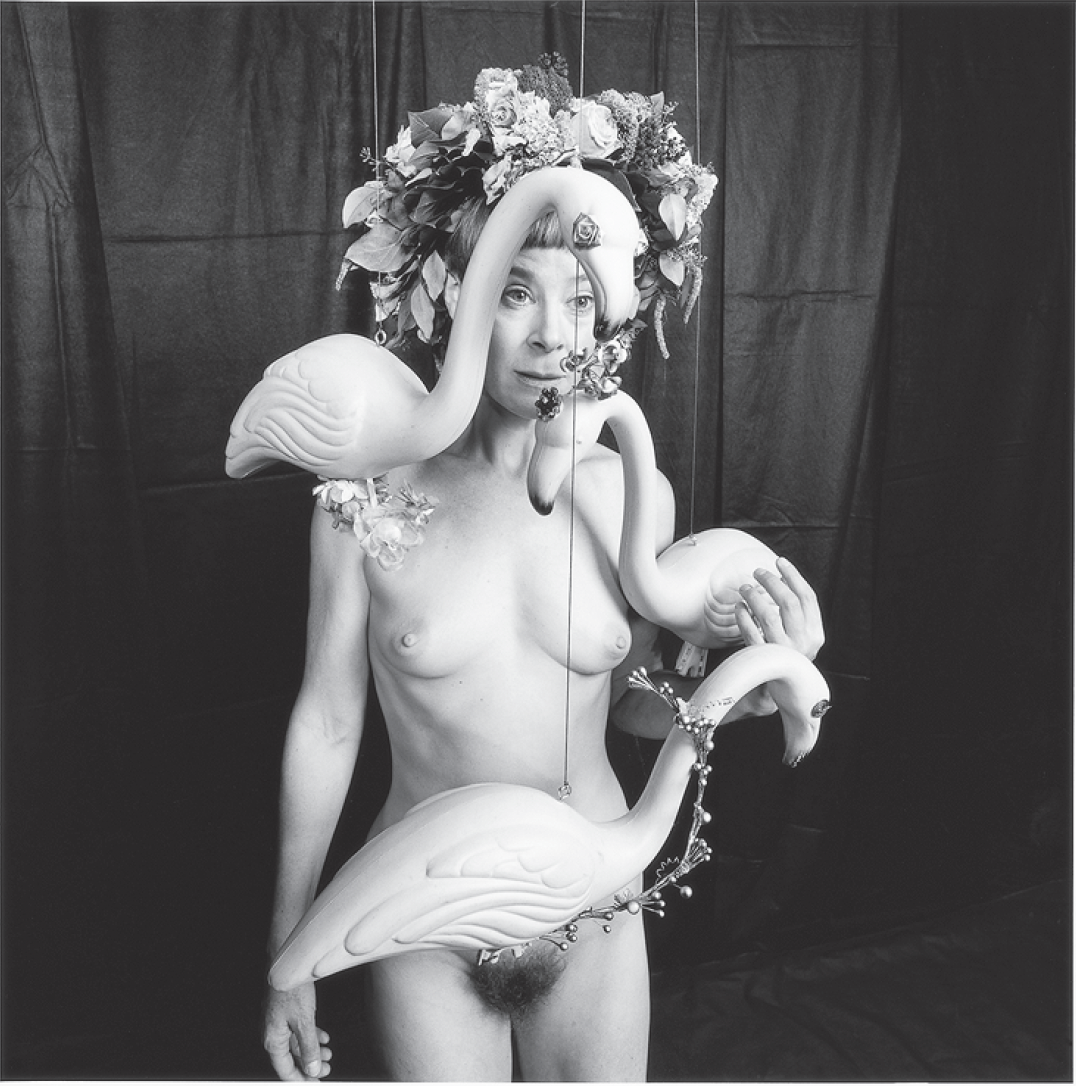

Now the images are flowing from hidden, or heretofore unspoken, desires. All kinds of performances take place. Only in “Extasis” can one find the “sexualized expression” that Jenkner sees as the thrust of the show; “the commodified sex dreamscape that is porn” is effectively travestied. The tableaux are mainly staged in people’s homes where their banal possessions mix it up with sex toys and improvised instruments of torture (a potted plant). Steeves, the trickster, also goes out into nature, where his re-enactments of photographic Modernism cast the imperfect, shopworn bodies of his nudes in a more poignant raking light.

George Steeves, Entropy No. 4 (VD), 1996, 45.7 x 32.2 cm.

To catalogue the subject matter and pretexts of this work is, in large part, to sidestep its driving force, which is photography. There is no other agenda here, and none should be imposed. If, as Schwenger explains, Steeves’s subjects appear to be refining Lacanian models of “desiring,” it is surely because each image has been formed from birth in layers of photographic recognition. He and his collaborators are complicit with the mirror-with-a-memory— they anticipate themselves as photographic figures. In “Extasis,” this may bring a sexual thrill—the pleasure of inviting the gaze of a stranger. In “E-Minor,” the very real risks of giving not just the body but the being are terrifyingly rehearsed.

Only Steeves and Heller are pictured in this section. Steeves appears in every photograph, his expressions often troubling, as he lays out the boundaries of his life. Gender, religion and nationalism act on a mute, cross-dressing, blasphemous, superannuated recruit who stands at attention, up against a brick wall. In the next frame, he is a weary clown in dessicated makeup, posing in front of a steel cabinet that holds his archival boxes and cameras— he is shy, he is almost ashamed. Some of “E-minor” has been created in Steeves’s studio space, other pictures fit themselves awkwardly into domestic interiors or industrial exteriors. Steeves’s poses with Heller are sometimes hilarious, sometimes tragic—the one always borrowing from the other as two aging actors ape matrimonial exhaustion and try new things to get off. In one, Heller is the picture of serenity with the jaws of a fur piece clamped around her exposed tit. Always, the camera is there, and acknowledged to be there, as the eroticizer of the moment. But the masterpieces of this section, and of the show as a whole, combine Steeves’s naked, vulnerable body with the instrument and symbol of his art: a jagged-edged, broken mirror. A mirror promises flattering reflection and it cheats. Too brittle to be handled, a mirror shatters; fragmenting space, amputating limbs and other bodily extensions, it recombines same in grotesque, picture-puzzle ways. In a climactic performance, Steeves and his shards kneel before the camera; he is simultaneously recorded in frontal and profile views, a man both doubled and dismembered. ■

“George Steeves” was exhibited at Mount Saint Vincent Art Gallery in Halifax from February 28 to April 8, 2007.

Martha Langford is a contributing editor to Border Crossings. Author of numerous books on photography, she is currently completing Scissors, Paper, Stone: Expressions of Memory in Contemporary Photography, forthcoming from McGill-Queen’s University Press.