General Idea

The stellar exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada encompasses the two-and-a-half-decade oeuvre of the prolific, mercurial Canadian artist collaborative General Idea. The trio of artists— AA Bronson, Jorge Zontal, Felix Partz, functioning as one entity—countered Canadian art-world conventions as well as public expectation of what artists should and could be. Coming out of the hippie and punk countercultures of the late ’60s and ’70s, General Idea emerged, almost accidentally, from a larger group of artists living communally in cheap housing at 78 Gerrard Street and later at 87 Yonge Street in Toronto. Merging art and life, their first works bore little, if any, expectation that they were, in fact, making art. Through a collaboration based on trust, generosity and common purpose, they sought free modes of artistic agency through a kind of anarchic dismissal and revolt against consumer culture and fine art rarification. Through unconventional interventions as diverse as mail art, photography, video and audio recording but also much writing, and taking inspiration from Fluxus and other groups, they not only challenged how art could be made but also questioned the necessity of the art object itself.

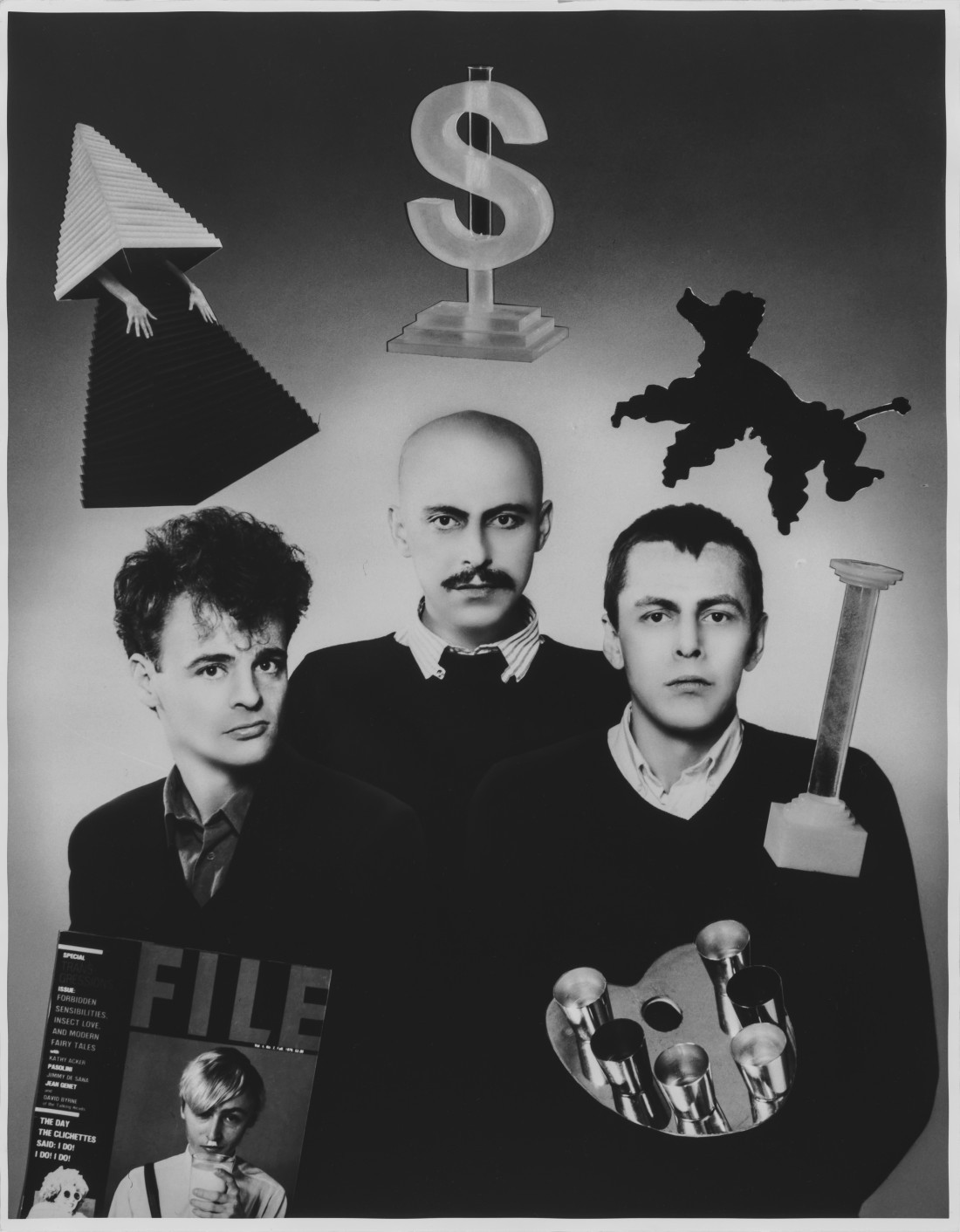

General Idea, Self-portrait with Objects, 1981–82, montage, gelatin silver print, 35.6 × 27.7 centimetres. Purchased 1985. Photo: NGC. © General Idea. All images courtesy National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

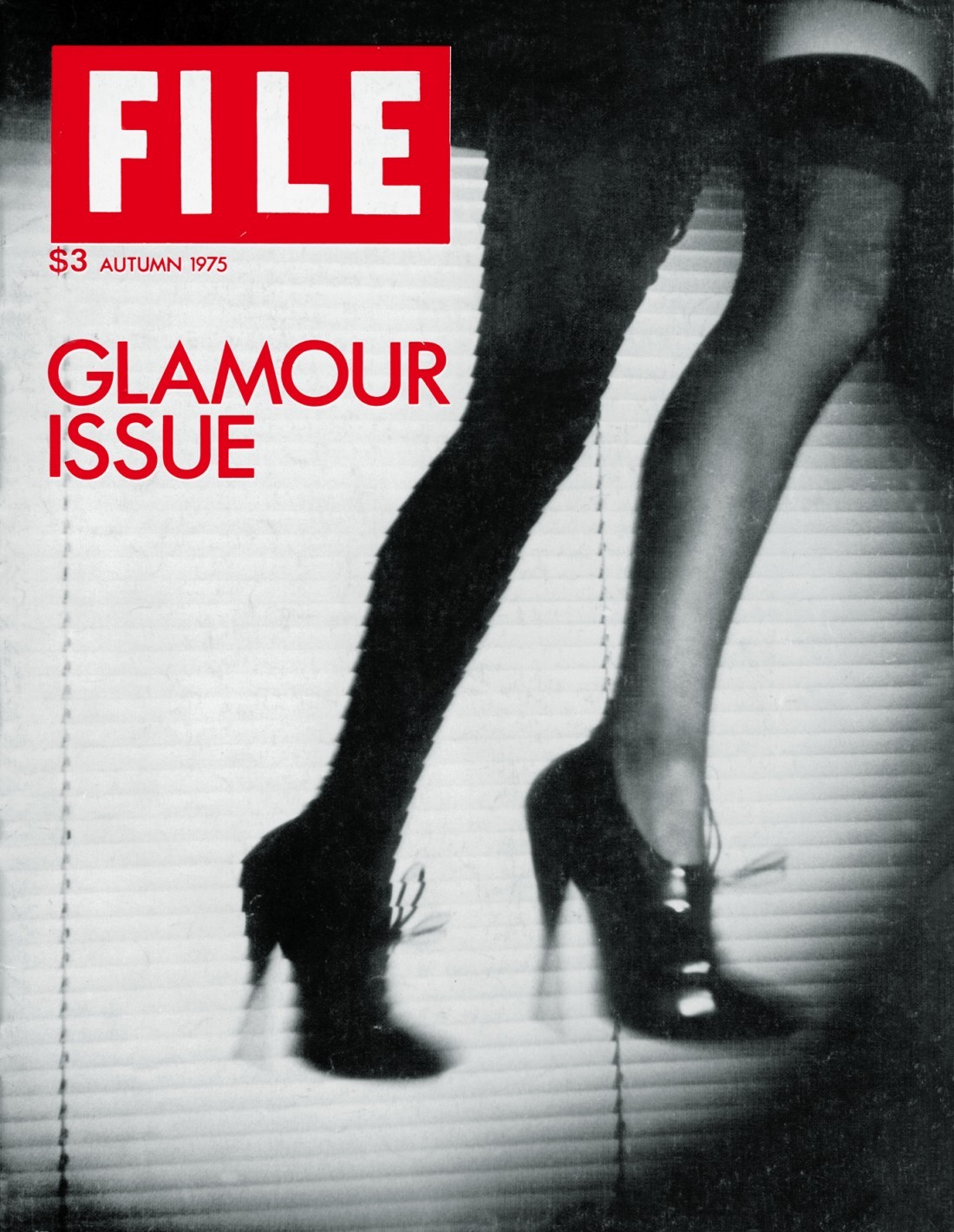

FILE Megazine, vol. 3, no. 1 (Glamour Issue), 1975, offset periodical, 35.5 × 28 centimetres. Collection of Art Metropole fonds; Art Metropole Collection; and National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Ottawa. Gift of Jay A Smith, Toronto, 1999. Photo courtesy the artist and General Idea Archives, Berlin. © General Idea.

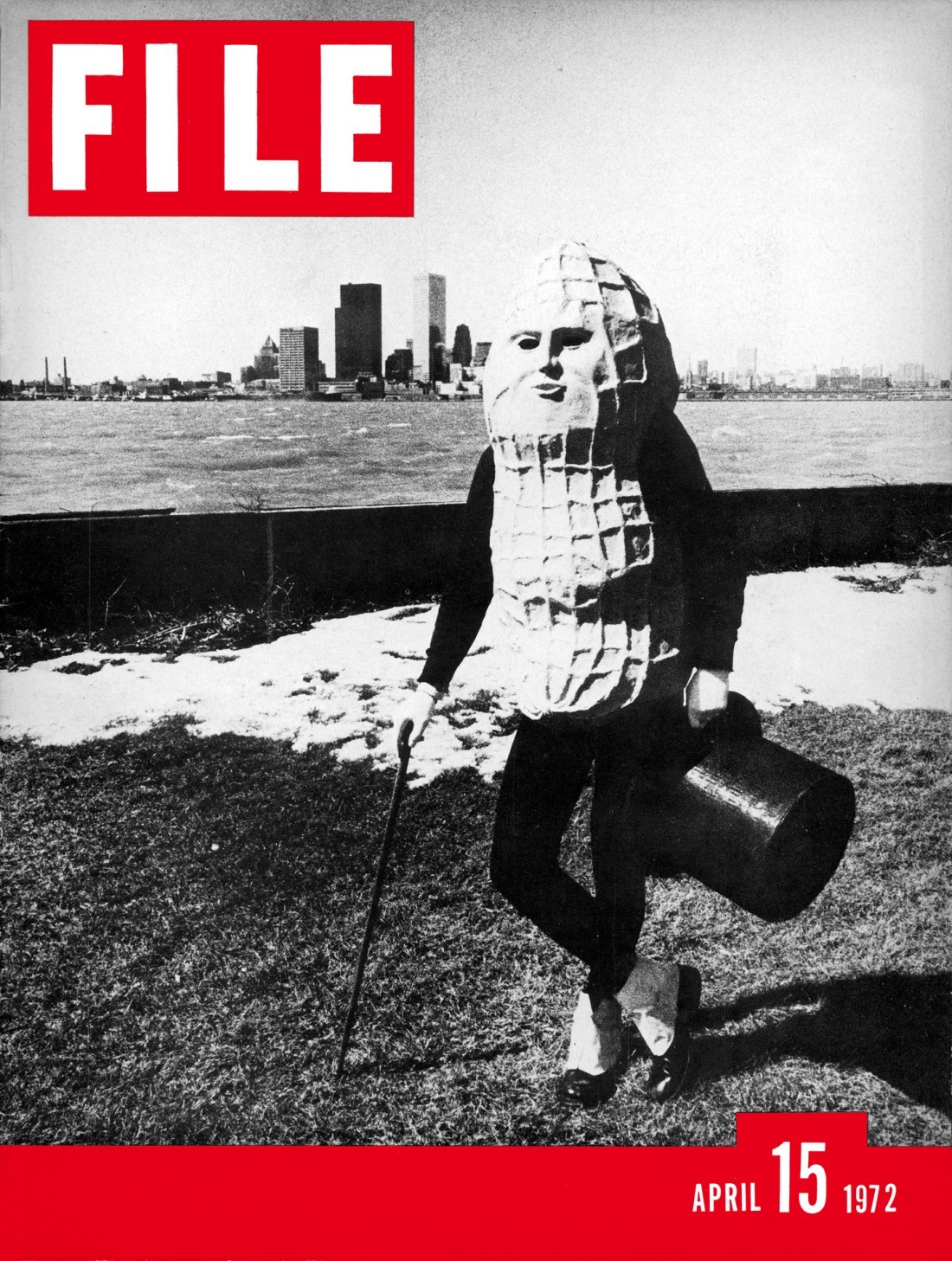

FILE Megazine, vol. 1, no. 1 (Mr. Peanut), 1972, offset periodical, 35.5 × 28 centimetres. Collection of Art Metropole fonds; Art Metropole Collection; and National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Ottawa. Gift of Jay A Smith, Toronto, 1999. Photo courtesy the artist and General Idea Archives, Berlin. © General Idea.

This exhibition does the near impossible: it attempts to summarize General Idea’s multifarious, idiosyncratic output through chronological curation and meticulous recreation of pre-existing works. The accompanying catalogue is jam-packed at 755 pages—a necessary compendium that fleshes out the multi-dimensional narrative with thematic essays and a plethora of photos. The overall result is an exhibition that both surveys and pays homage in equal measure, sharing their story (in many ways long overdue) with attentive care.

In the atmosphere created by Andy Warhol’s pop glamour and celebrity fetishism, General Idea sought to dispel the myth of the solitary artist as genius, preferring the more radical position of interconnected co-authorship. To reach as wide an audience as possible, they quickly adopted any and all mass media strategies available. Concurrent with their projects was the publication FILE Megazine, for example, a bold platform created as a catch-all for finding and defining the General Idea narrative. It was instrumental in defining their (can we even say branded?) identity, and as such becomes the locus through which their aesthetic and conceptual dynamism could be accessed.

Encircled by the flags and banners collected in The Armory of the 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion, 1985–90, one of the gallery’s exhibition spaces felt like a paean to the raucous and optimistic ’80s. Part punk signage, part medieval coat of arms, the shield-shaped emblems hung high on the wall, broadcasting the group’s core iconography—curly furred poodles, tweed patterns, crescent moons, skulls, ziggurats and arabesque Hotrod flames. In fact, the exhibition was everywhere energized by a strategic and unapologetic use of colour combinations of DayGlo and fluorescent poster paint alongside matte black— painting performing as poster signage, personalized logo and protest banner. Their iconic green, blue and red are ever-present here, too, a recognizable chromatic triad repeated throughout the exhibition that would eventually become synonymous with their name.

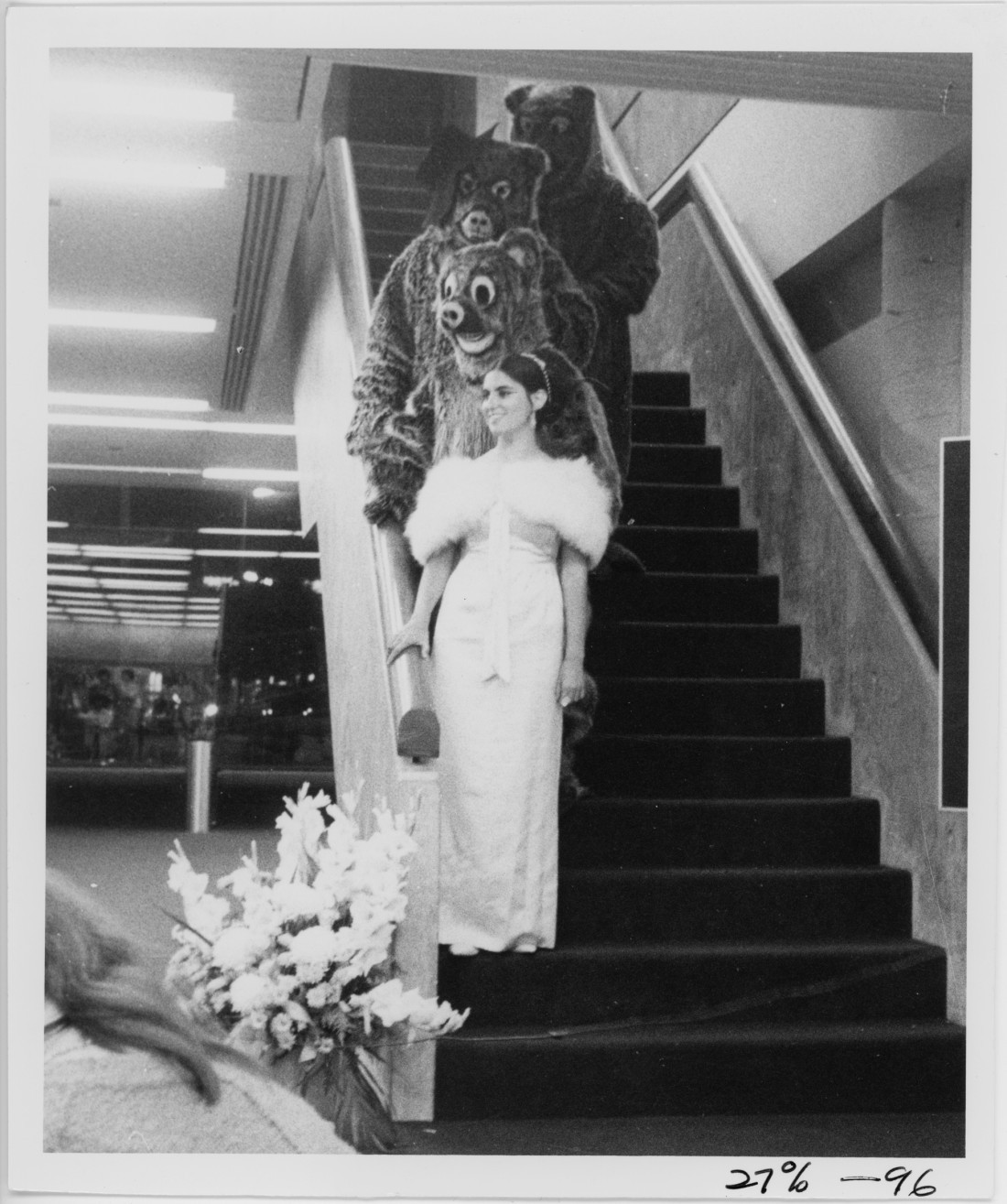

The 1970 Miss General Idea Pageant, 1970, performance as part of “What Happened,” St Lawrence Centre for the Arts, Toronto. Photo: NGC. © General Idea.

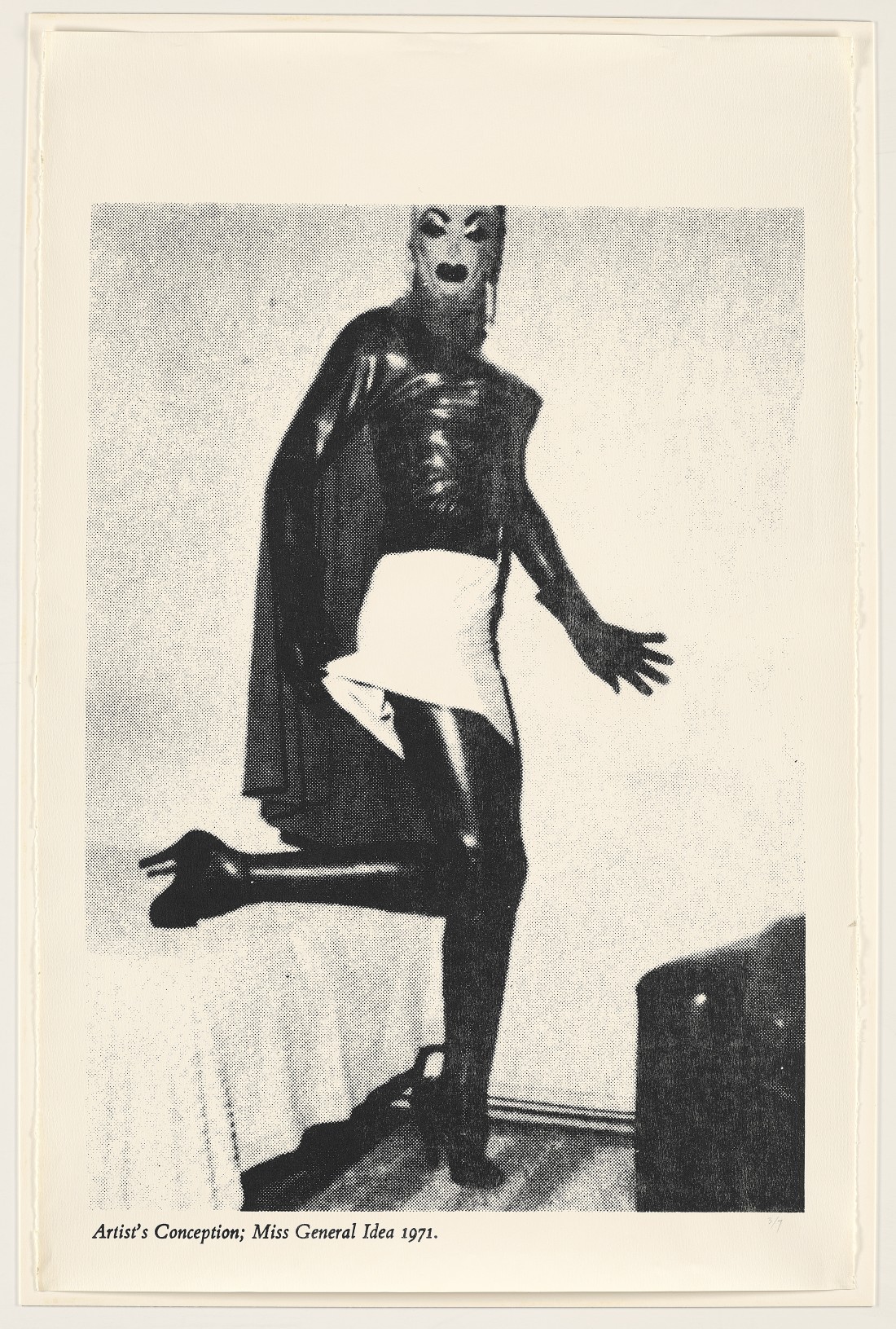

Artist’s Conception: Miss General Idea 1971, 1971, silkscreen on paper, 101.5 × 66 centimetres. Collection of Art Metropole Collection and National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Ottawa. Gift of Jay A Smith, Toronto, 1999. Photo: NGC. © General Idea.

A linking corridor is devoted to early relational projects such as AA Bronson’s Tour de Force, composed of a beat-up salesmanstyle black binder of photographs he hawked to museums and galleries across Canada in 1970. The Index Cards, displayed individually like drawings, reveal a restless, expansive play of language in search of new ways of opening intellectual and affective space from which to act.

The DIY-inspired early work believed art could come from nothing and leave little, if any, trace. The trio would later expand relational gestures into large-impact actions that challenged the separation of performer and audience while blending ‘art’ content and socio-political context. In doing so they probably contributed more to the dissolution of Canadian high and low art designations than any other artist, collective or otherwise.

Fin de siècle, 1990, installation of expanded polystyrene with three stuffed faux seal pups (acrylic, glass and straw), dimensions variable. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 2022. Photo: NGC. © General Idea.

The Miss General Idea Pageant project, their seminal spectacleas- artwork, which AA Bronson called a “violent intrusion into the heart of culture,” was held at the Art Gallery of Ontario on October 1, 1971. It was a performance intervention that had all the components of a mainstream broadcast event: 13 contestants in brown taffeta gowns, a directed audience of over 400, plus a video crew recording all the action. It celebrated their love of spectacle, glamour and above all campy irony, which would carry over into multiple projects. Again, promotional ephemera became the art itself. Installed salon-style were large posters, letters of formal invitation, recorded audio and mailed-in photos from the hopeful contestants, and all became traces—documentation as the de facto artwork; the power of exclusivity, mystery and dazzle was co-opted to create hype and infamy. As audience, we remain on the outside looking in: voyeurs left to imagine the glamorous event through the ephemerabecome- relic. The collective itself, they assert, and not institutions or the market, controls their epic semi-fictional narrative.

Their negation of art commerce was short-lived, however. The ’80s was a time of rapid calibration of the opportunities and restrictions of their new-found fame in Europe and the US. Black and white prints were replaced by seductive large-format colour photography such as the technically flawless Nazi Milk, 1979–80 (printed by hand by Zontal), and paintings—albeit made out of glued macaroni— shout back cigarette logos reduced to geometric abstraction. For a moment, it appeared as if they had been absorbed into the money-driven spectacle they once railed against. The artist’s hand is barely visible except in the delightfully shoddy sets for their videos and shockingly tasteful pointillism of the atomic bomb paintings.

In the afterglow of the never-realized 1984 Miss General Idea Pageant, a host of works were born, such as the full-on commercial Boutique, 1980, a kiosk of galvanized metal, recreated by gallery technicians, in the shape of a big 3D dollar sign that hawked massproduced items such as postcards, quilted appliqués and other small multiples, just like a museum shop. Designs for the Pavillion project expanded over the years into new visions, as in Legend—a grand hall entrance with St Sebastian-like nudes bound to leopard-print pillars.

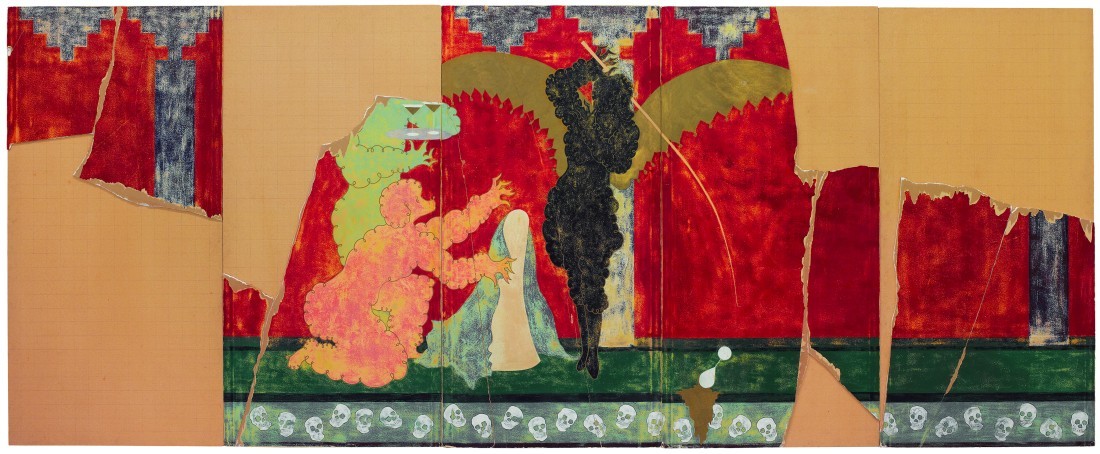

General Idea remained counter to art-world machinations in the economic boom of the ’80s by embedding an increasingly unapologetic queerness into every work they made. They revelled in the erotics of materialized artifice. Sexuality and queerness were indispensable to their conceptual intent and were parlayed with increasingly shameless humour, parody and ironic glee. Through image- and word-play set inside a semi-fictional narrative, they successfully used strategic ambiguity about the real and unreal to embed a queer sensibility. A covert doubleness appears in all their gestures, so it is not surprising their language is a mix of mock official speech, conversational intimacy and free-form poetic banter with titles like Tableau Vivant, Natura Morta, a work that is part of a larger group of paintings called “The Mural Fragments”—a series of rescued relics salvaged, we are told, from the destroyed The 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion. These are composed of plaster fragments ragged and broken into odd shapes as if torn directly from the walls of Pompeii. Three frolicking poodles, appearing in each work in the series, are playful, licentious and unaware of our gaze—enraptured agents of libidinous freedom. At the time, no critic discussed the overt homosexual content, much to the chagrin of General Idea. These hybrid, mystical beings existed in-between worlds, disordering a sense of the ancient and modern, taunting a reversal of the sacred and profane in simulated Kama Sutra poses. The paintings are at once tender, bold and irreverent, delicately built with finely wrought surfaces of multiple paint layers hand-sanded and scraped into faux-antique patinas. Like the explicit murals left uncensored in another age, these relics resurface into the present to titillate, delight and create their own destabilizing havoc.

The Three Graces (Mural Fragment from the Villa dei Misteri of The 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion), 1982, latex enamel on wood, 246 × 218 × 5 centimetres. Collection of Vancouver Art Gallery Acquisition Fund. Photo courtesy the artist and General Idea Archives, Berlin. © General Idea.

The Unveiling of the Cornucopia (Mural Fragment from the Room of the Unknown Function in the Villa dei Misteri of The 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion), 1982, enamel on plasterboard and plywood, 244 × 610 centimetres. University of Lethbridge Art Collection, purchased 1986 with funds provided by the Canada Council Special Purchase Assistance Program. Photo: Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. © General Idea.

AIDS, 1987, acrylic on canvas, 182.9 × 182.9 centimetres. Photo: Blondeau & Cie. © General Idea. Private collection. Courtesy Blondeau & Cie.

Installation view, “General Idea,” National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 2022. Photo: NGC. © General Idea.

Installation view, “General Idea,” National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 2022. Photo: NGC. © General Idea.

Pharma©opia, 1992, urethane and nylon blimps, helium. National Gallery of Canada. Photo: NGC. © General Idea.

One Day of AZT, 1991, 5 units, fibreglass, 85 × 214 × 85 centimetres each. Gift of Patsy and Jamie Anderson, Toronto, 2001, and One Year of AZT, 1991, 1825 units, vacuum-formed styrene and vinyl, 12.7 × 31.7 × 6.3 centimetres each. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, purchased 1995. Installation view, “General Idea,” National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 2022. Photo: NGC. © General Idea.

The “Mondo Cane” paintings, Mondo Cane Kama Sutra 9 figures #1, 1983, and Mondo Cane 2 (Nine Figures), 1984, satirize one step further. As if using Frank Stella’s own ruler and stencils, the geometric poodles turn abstract reductiveness on its head by replacing pure forms with orgiastic scenes. The group called this series their first overtly queer statement because they were bending painting’s straightness towards their own emancipatory ends, Alex Kitnick’s essay in the catalogue tells us.

General Idea imbued all their objects with a secular magic. The human-scale sculptures Monday, Wednesday, Saturday, 1984, stand among the paintings as phallic presences of vitality and protection. Authenticated with cracking plaster and abraised paint, the totemic pillars are like idols from another, more enlightened time when sex was worshipped openly and was without guile. The ziggurat paintings’ tiered puzzle shape is a simplified form inspired by the Middle Eastern temple motif Zontal found in Mesopotamia. Using repeating, interlocking modular motifs, sometimes on shaped canvases in the manner of Stella, and painted with fluorescent abandon, they radiate outwards in potential ascension and transformation to suggest an infinite unfolding.

Then, all at once, the work shifted away from satirical exuberance. In 1986, shortly after General Idea moved to New York, the rising AIDS crisis brought urgency and grief to the group and their circle. In immediate response, a sombre elegy descended into their work as they began the large, imposing AIDS paintings (a scathing swapping of Robert Indiana’s hopeful L-O-V-E works) and large posters, first plastered on the walls of the Toronto subway system. They returned to the immediacy of print: graffiti became their modus operandi, demanding maximum impact on the urban stage. Pop revelry was now conceived as an image virus so that their message could be (as Bronson says in “Myth as Parasite/Image as Virus”) “injected into the lifeblood of the communication, advertising and transportation systems” of the street. These final works embody a counteraction against growing social antipathy in what Judith Butler calls (in their latest book The Force of Non-Violence) an act of “mourning as militancy.” With single-minded purpose they fought the tendency in media to make invisible the victims of a publicly stigmatized epidemic.

The monumental, paradoxical Fin de siècle is comprised of hundreds of sheets of Styrofoam insulation standing in for Arctic ice. Encircled there are three startled baby seals, made also from plastic, becoming ghostly semblances of the natural subsumed into pure artificiality. Illuminated in Dan Flavin’s ubiquitous fluorescent light, the disparity of the natural subject and its airy materiality leaves an irreconcilable void into which the viewer must project their own meaning. The seals are impossibly vulnerable, cute and helpless, begging a universal collective pathos. I read a complicated commentary about identity, personhood, lovability, authenticity and threat. “Don’t gay and marginalized lives deserve the same protective outcry?” it seems to ask. The viewer is left with a conundrum whereby irony suddenly becomes imbued with an ethics that overrides all other aesthetic, or even ecological, concern.

In the final segment of the exhibition, the iconic AZT pill room was overwhelming with variously scaled pill replicas representing a year’s worth of doses. When the viewer entered, the glossy vacuousness of cast plastic, serene under cold light, felt like both a whispery tomb and hushed hospital, the large ovoid shapes standing like sarcophagi the size of palliative care beds. Though representing the promise of survival, the engulfing space felt like a monument to mortality, loud as a howl. Blankness dissolved into what Piero Manzoni had termed the “Achrome,” a denunciatory colour of white acting as stand-in for cultural erasure and imposed silencing. True to their activist beginnings, these works hold witness to the harm of collective phobia and cultural oppression, and continue to stand as unambiguous protest.

Courageously and defiantly, with an even bolder candour, the theme of body- and sex-positivity remained front and centre in the last works. In the middle of the final room, on a tri-colour tiered plinth that reads also as Fifth Avenue-style floor display, sits a cluster of glass-cast sex toy multiples titled Dick All, 1993–2001; knock-off Mondrians cover the walls. Heart-shaped images of the INFE©TED Coeurs Volants, printed in concentric sanguine red, nocturnal blue and green, repeat across shiny silver Mylar wallpaper. The entire scene is an engulfing mirror within which the viewers may see themselves reflected, and invited, to be aware of their own (body) presence and to turn their gaze inward in an internal reckoning. Framed against today’s commodity culture proliferation and cultural conservative turn, this last summative installation suspends us in a void resting just outside any fixed orders of meaning, which is precisely where General Idea’s art wants us to stay. ❚

Martin Golland is an artist in the Capital Region and a professor of painting in the University of Ottawa’s Department of Visual Arts.

Order Issue 161 here.