Genealogies of Blood and Breath

As a child I spent several summers at Fort San on the banks of Echo Lake in the Qu’Appelle Valley. Although, at its inception in 1917, Fort San represented the earnest desire to care for and protect society from the ravages of tuberculosis—the first plague of the 20th century—I knew it only as an arts school. The echoes of crying children and rattling gurneys had been replaced by the chirping of wind instruments and that particular brand of exuberance only liberation from your parents can yield. There are endless, cavernous passages in the bowels underneath the San where, on particularly mischievous occasions, we would test each other’s mettle and venture forth armed only with the incandescent glow of our flashlights. But even before I knew or understood what a sanatorium was, I could sense death in the massive stillness of the place.

In the powerful video and bookwork, THE BLOOD RECORDS, written and annotated, Lisa Steele and Kim Tomczak masterfully capture the complex mysteriousness of the San and the enormous weight of its memory and silence. THE BLOOD RECORDS is structured like a classical play with a prologue and three acts. It opens to an overexposed, almost white screen with the camera passing quickly over what appears to be a field of wheat, while in the background we hear the venerable Leadbelly singing his “TB Blues.” At just over two minutes, this opening scene draws the viewer out of the sporadic and disposable time of television into the reflexiveness of video.

The first “act” is a collection of didactic educational footage instructing the viewer, in detail, on the benefits of cleanliness and how to avoid transmission of disease. It pits the mucky recklessness of the domestic (gendered female) domain—where tasting junior’s food and kissing your sweetie are dangerous activities—against the cool sterility of the scientific (male) domain of the clinic or hospital. Yet, despite the confidence and paternal swagger of the narrator’s voice, desperation and uncertainty lurk beneath the surface. As one of the doctors in the footage testifies, “I can really see this ancient misery disappear,” I can’t help but compare it to the tentative sort of optimism surrounding the still elusive AIDS virus.

THE BLOOD RECORDS, video and bookwork, Oakville Galleries, Oakville. Photographs courtesy Dunlop Art Gallery, Regina.

Cut and fade. Now the camera is floating over the Saskatchewan Legislative Buildings. It is July 10, 1944, and T.C. Douglas is being sworn in. As the video depicts the inauguration of Canada’s first socialist government, it likewise sheds light on the current struggle to maintain Douglas’s vision. (Who would have thought that after 66 years and the development of universal medicare in Canada, we would now be at the cusp of its dismantling?) The footage then shifts to pilots boarding fighter planes, since 1944 was also the year the Allied forces landed in Normandy. Steele and Tomczak examine the conflation of Saskatchewan’s rising identity as a province, and its involvement in both the external war of bombs and planes, with the internal struggle to maintain control over the body, to contain the sputum and blood that carries the enemy within it.

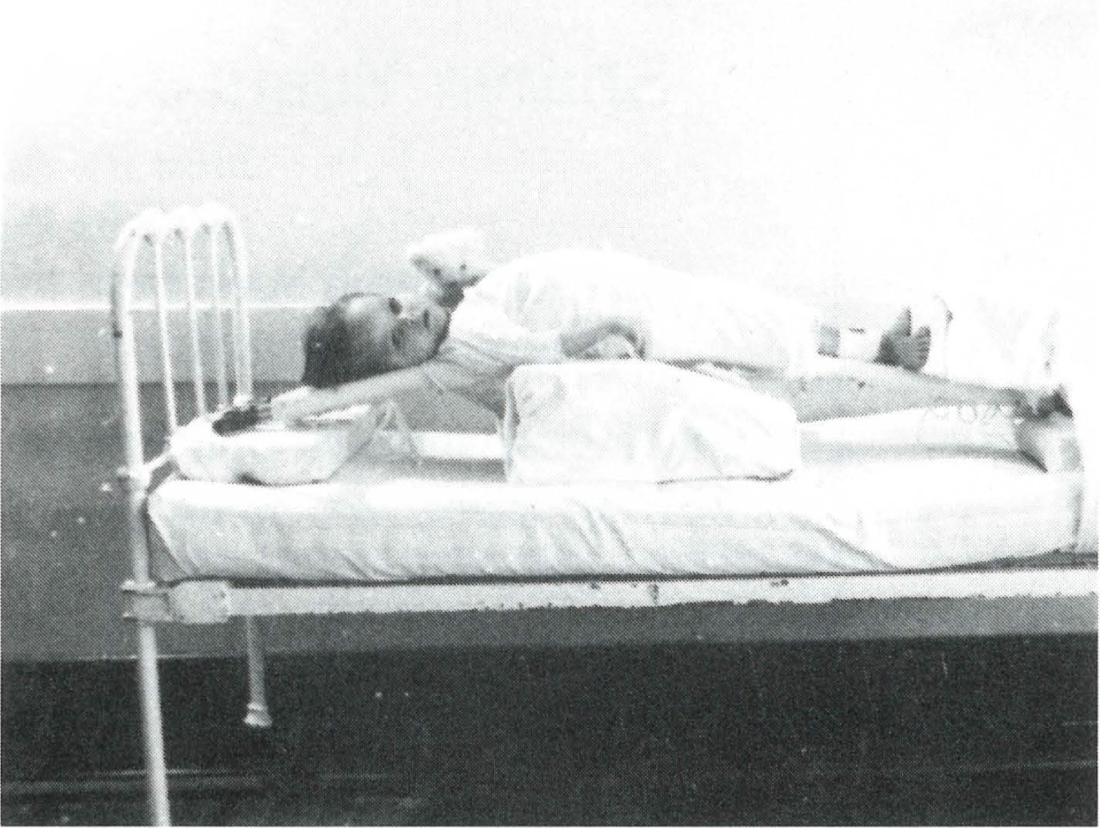

THE BLOOD RECORDS then moves away from ministerial decrees, government agencies, official policies, into the private, personal struggles and the daily routine of those inflicted. Every minute of every day is carefully scheduled and monitored. During “rest cure” patients are to avoid all stimuli; this includes reading, talking, and listening to the radio. Weight loss was a sign the germ was winning, thus an average mid-day meal was a colossal event consisting of stuffed chicken, cream of corn soup, corned tongue, potatoes, plum pudding, vanilla jelly, and bread and butter. Two to three glasses of fresh milk were consumed three times a day. Brooding thoughts and excessive worrying were discouraged. As the video states, “Worry, self-pity, discontent and self-destruction: these were the Four Horsemen of Destruction.” This claustrophobic attention to the minutia of daily life is troubling, not in its almost overwhelming demonstration of state control, but rather as a contrast to the present condition where even when treatment is absolutely necessary, there simply aren’t enough beds.

In the third and final segment the perspective continues to zoom closer and focusses on Marie, a young girl loosely based on Steele’s and Tomczak’s mothers, who both spent time in sanatoriums. Marie’s voice emerges, disembodied, through the darkness of an empty screen: “I’d already been in the San for over a year when I ‘broke down’. Following my breakdown, I was confined to bedrest for 209 days. During that time I was not allowed to lift a spoon to my lips nor to hold a book nor to look out the window.”

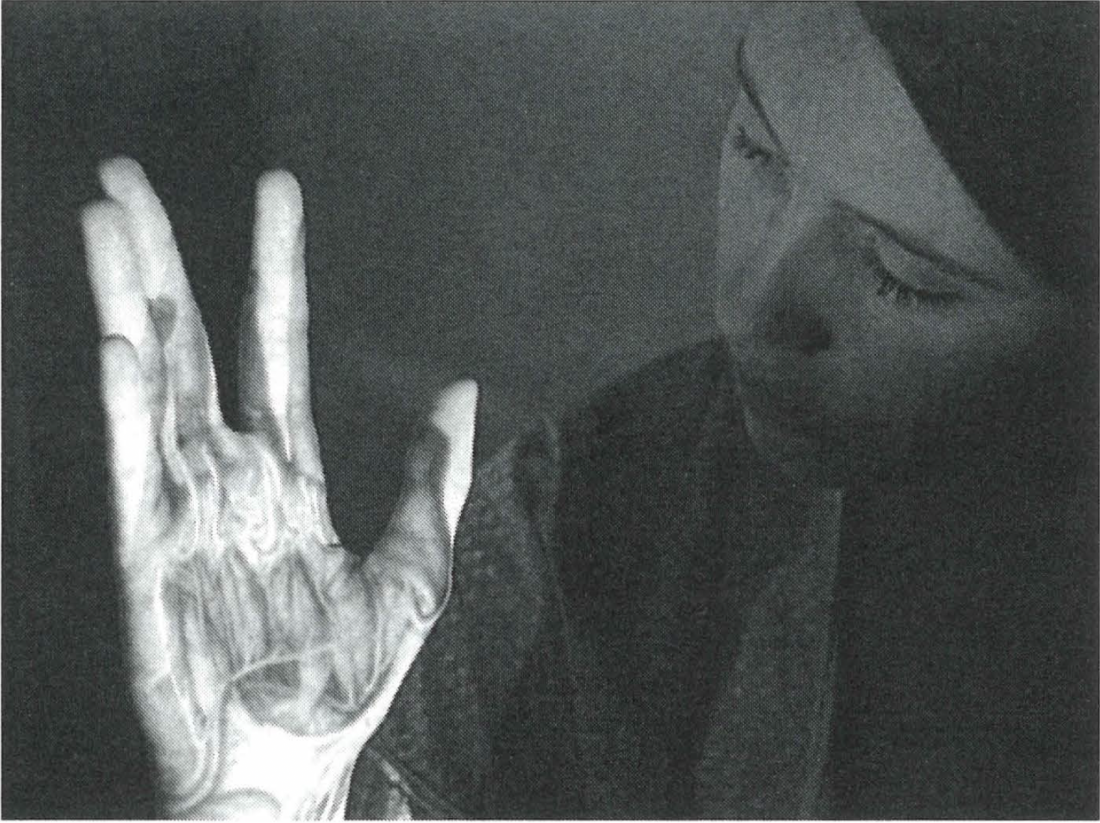

In a struggle not unlike that of Sisyphus, Marie survives the enormous psychic weight of endless hours of silence and stillness by separating her being from her physical self: “It was at this time that I learned to fly, to travel anywhere I wanted to without moving.” This disembodiment is echoed by her loss of language and identity.

THE BLOOD RECORDS, video and bookwork, Oakville Galleries, Oakville. Photographs courtesy Dunlop Art

At odds with herself and embarrassed by her French roots, she states, “They say ‘mother tongue’ but I always think of French as the language of my father and, when I was 13, I wanted to lose it as soon as I could.” This desire is a self-fulfilling prophecy, since the voice coming through the pictures is Anglo without the slightest Francophone inflection. An almost cannibalistic detail with uncomfortable resonance is that she is served corned tongue for lunch and tongue again for supper. This eating of oneself, the placing of the mouth at the centre of both the development of identity and its demise, is again echoed when her father, disgusted by her English, “would eat [her] words whole if he could just to keep from hearing them anymore.” But the mouth is also the location of freedom, of survival, because the act of remembering and telling is a testament to Marie’s endurance, a challenge to the nullifying silence.

This narrative shift from the macro environment of institutionalized control to the personal struggle of young Marie moves THE BLOOD RECORDS away from a tight commentary on tuberculosis and the San into a more open, fluid rendering of suffering and our attempts to manage it. It becomes a powerful treatise on the state of compassion and our willingness as a society to offer care to those desperate for it. In their moving docudrama, Kim Tomczak and Lisa Steele have gone inside the overbearing presence of the San, mute and heavy with absence, to liberate those voices that never told their stories.

The bookwork accompanying the video is a two-volume package complete with colour reproductions and remarkably moving archival footage. Steele and Tomczak worked closely with designer Lewis Nicholson to create a beautiful book that not only serves as accompaniment to the video, but stands alone as a compelling and original document. The first volume, THE BLOOD RECORDS, written and annotated, opens to an x-ray photo of a chest and lungs, and moves through unsettling images such as those of children lying side by side, gazing through feverish eyes with varying degrees of indifference and boredom. Then, an image I found almost impossible to look at. Staring straight into the lens is a small, two- or three-year-old girl clutching her teddy bear. She is tied down and stretched out, back arching over a shell designed to prevent spinal deformities as the virus moves through the bones. It is unimaginable what these “shell patients,” often in this position for weeks at a time, must have gone through. The book concludes by giving a chronology of tuberculosis treatment in Saskatchewan, which draws interesting parallels between the development of the province and the spread and treatment of the disease.

The second volume, THE BLOOD RECORDS, Critical Symptoms, presents a series of essays designed to set the stage for an informed reading of the tape while closely examining and celebrating the collaborative work of the artists. Su Ditta’s piece, “Eyeing the Sublime: Poetic Politics in the Work of Lisa Steele and Kim Tomczak,” traces their practice over almost 20 years and charts their deep commitment to artist-run centres, political change, and the development of video. Mike Hoolbloom’s “Mourning Pictures” is a deeply felt, poetic response to the tape. Originally written as a letter to the artists after attending the première screening at the Museum of Modern Art, Hoolbloom’s critical commentary reads more like an elegy, offering the reader profound insights into death, disease, and dying. Johanne Lamoureux’s essay “The Blood Records: Idle Identity” looks at the ways in which the mouth is the centre from which spiral out the infections of language, identity, and disease. Now part of Oakville Galleries Permanent Collection, THE BLOOD RECORDS is an epic event in the history of video art in Canada and an achievement that must surely be celebrated. ■

THE BLOOD RECORDS, written and annotated was organized and toured by Oakville Galleries. It was on exhibition at the Dunlop Art Gallery, Regina, from January 8 to 23, 2000. The bookwork was launched at the Oakville Galleries, Oakville, on January 14, and at the National Gallery of Canada on January 22.

Sky Glabush is a painter and critic who lives in Saskatoon. His work will be exhibited at the Mackenzie Gallery in Regina in July and at the Paul Kuhn Gallery in Calgary in August 2000.