Gego

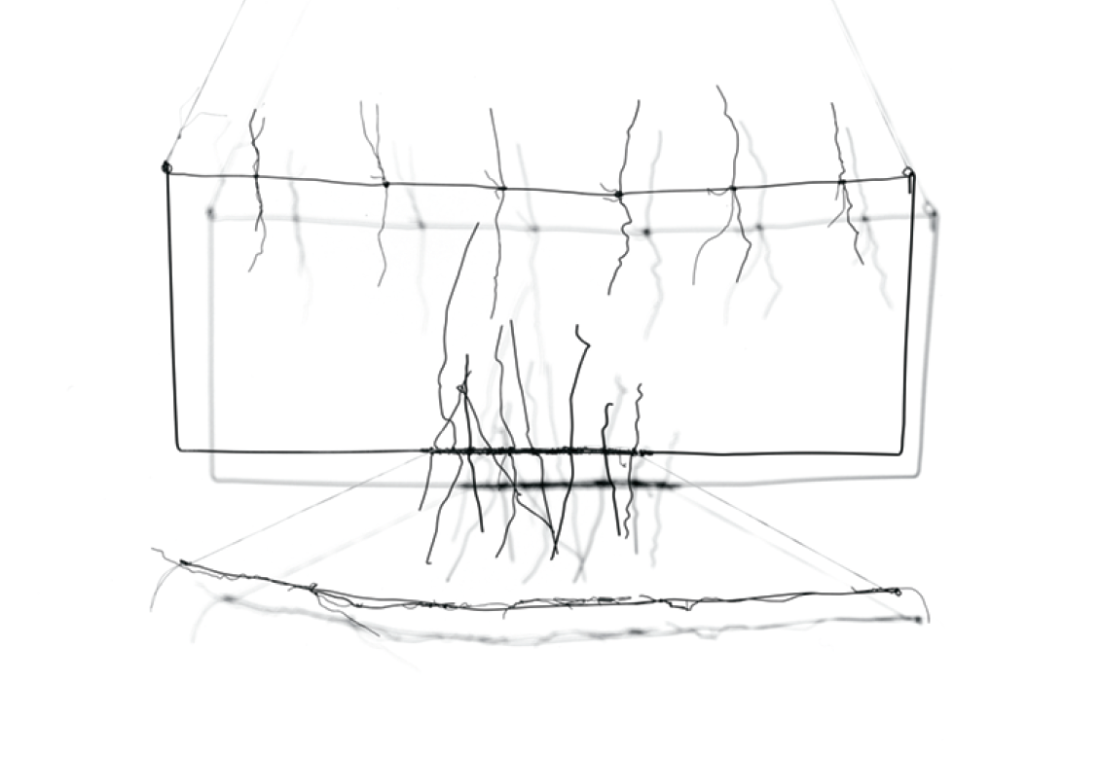

One of the first real hints we get of abstraction is in grade-school math: volume. After the reassuring tangibles of height, width and weight, the discovery that “empty” space is not formless dictates a complete rethink. Gertrud Goldschmidt, the German- Venezuelan known professionally as Gego, jogs that memory. With her signature simplicity of line in traditional drawings and especially the singular tissue of noded wire in her “drawings without paper,” Gego makes even air currents nearly visible. Fluid and responsive, her work appears to detect shapes and forms in the air itself, to draw out what was unseen though always present.

In “Gego, Between Transparency and the Invisible,” New York’s The Drawing Center featured selections from a larger survey at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston organized by the curator of Latin American art, Mari Carmen Ramirez. Despite a crowded installation and sometimes too-weak lighting (peculiar, given the crucial role shadows play in this work), the exhibition located Gego as a pioneer in non-representational drawing, one of the first to dispense with paper itself. By creating gossamer structures more slight even than their shadows, Gego freed drawing, allowing lines to float untethered.

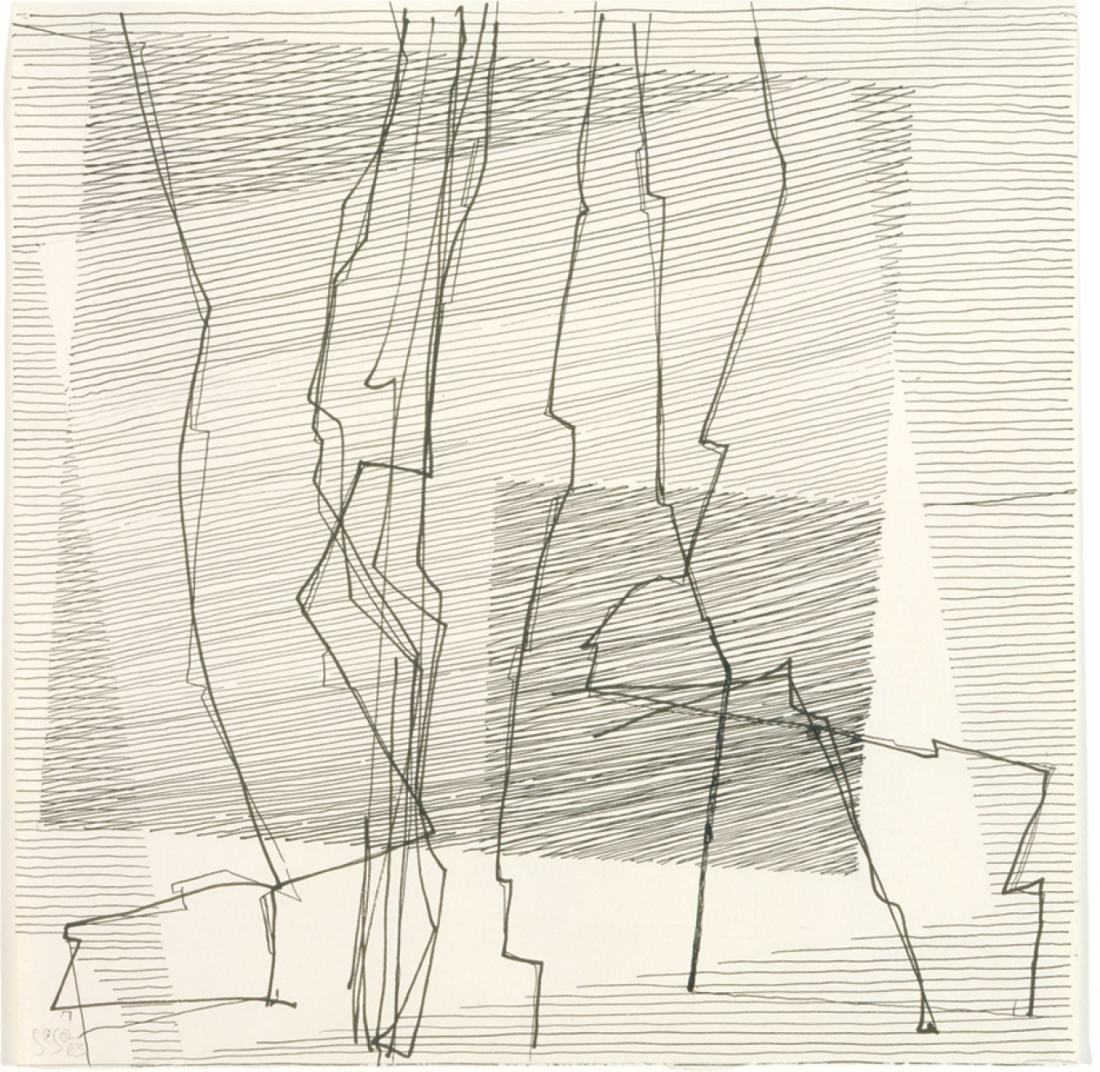

Gego, Untitled, 1963, ink on cardboard, 11 3/16 x 11 3/16”. All photos courtesy Fundacion Gego Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, © Fundacion Gego. Photographs courtesy The Drawing Center, New York.

Born into a Jewish banking family in 1912 in Hamburg, Germany, she intended to make a career in architecture and engineering. By 1939, Third Reich realities forced her to abandon Germany in favor of Venezuela, where she found work in architecture, married and raised two children before her marriage ended. By then in her 40s, she met and was encouraged by Gerd Leufert, a Lithuanian designer and painter. She remained with him and in Venezuela until her death in 1994.

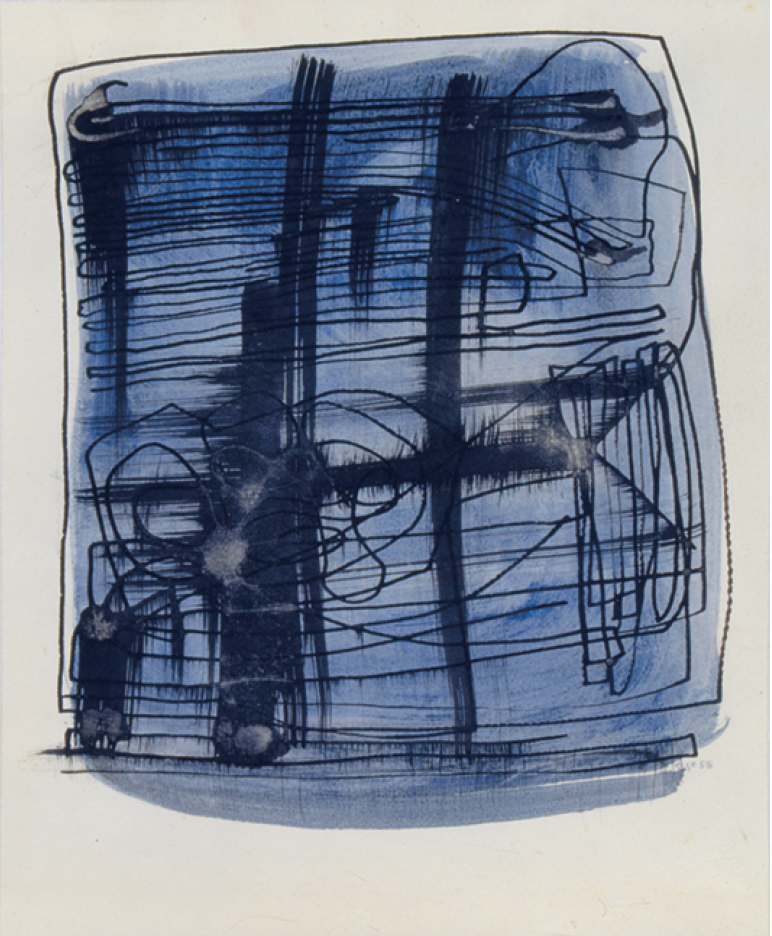

She described the urge to make art as a process begun “in the eyes and the hands,” a sensibility that informs even her works on paper. One of the earliest pieces shown here, a 1955 untitled abstract drawing, incorporates the acute angles and open-ended triangles of a 1983 drawing without paper, composed of nuts, bolts, washers and painted saw blades. Even before she began scoping out three dimensions, her works on paper had a nitty-gritty, tactile sensibility that undermines their superficial links to Constructivism. But she ignored any such label, pointedly stating that “my interest and work in the visual arts have developed gradually thanks to a set of factors and mainly, to my background as an architect.” Gego’s angles and grids have much in common with Agnes Martin’s, both artists taking their cue from natural effects, rather than a direct mimicry of nature itself. In Gego’s works on paper, lines snag and tangle and sometimes even seem to sway. The feeling is of currents perceived rather than order imposed.

Gego, Untitled, 1955, watercolour and ink on cardboard, 10 15/16 x 9 1/16”

Her “drawings without paper” demonstrate her mastery of the inherent properties of the modest bits of wire, mesh, cellophane and metal scraps she combined into sums far larger and more elegant than their parts. In Sphere No. 5, 1977, a geodesic assemblage of steel wires and black metal clasps, the wire connections are so delicate that they all but disappear in the shadow cast by the piece. What registers instead are tenuously connected dots, undermining the physical reality of the construction itself. Gego uses shadows to anchor the paperless pieces, providing counterintuitive ballast merely through the deprivation of light. Other suspended pieces, irregular constructions of metal rods, sprung springs and coated wire, seem on the verge of dissolution, of becoming completely their own shadow.

In Reticulárea, 1975, a large filigree of steel wire, its resemblance to an actual membrane is less fanciful than scientific. The piece appears to bulge, as if breath-filled, with a few larger areas and seems separated from a greater whole: a specimen. There was a sense of being enveloped in the work, the shadows a tangle of membranous branches limited only by the rather narrow confines in which the piece was installed.

Gego, Dibujo sin papel 86/6 (Drawing without paper 86/6), 1986, iron wire, copper wire and thread, 12 3/16 x 17 ½ x 1 3/8”

In Streams, 1970, life-size painted iron wire and aluminum rods cascade against a pedestal, a river arrested. Sheafed and held together by metal clasps, the coruscating rods seem softened by the play of light on their surface. Gego suggests metal’s ductile quality, the molten beginnings to which it can quite easily be returned.

Though there are affinities with Eva Hesse’s work and with Richard Tuttle, it is fellow architect Louis Kahn who catches her spirit: “When you want to give something presence, you have to consult nature. If … you say to brick, what do you want, brick? And brick says to you, I like an arch…. Arches are expensive, and I can use a concrete lintel over you. What do you think of that? Brick says: … I like an arch.” Gego, like Kahn, investigated rather than instigated. Her patient inquiry and elegant investigations reveal the improbable, exhilarating capabilities of mesh, wire and junked metal to etch against the void, gracefully. ■

“Gego, Between Transparency and the Invisible,” curated by Mari Carmen Ramirez, was exhibited at The Drawing Center in New York from April 21 to July 21, 2007.

Megan Ratner is a regular contributor to frieze and Art on Paper, and is Associate Editor at Bright Lights Film Journal.