Gary Pearson

Gary Pearson’s latest solo exhibition , “Short Fictions,” offers a glimpse into the mind of a cosmopolitan artist-as_philosopher. As you enter the gallery, you encounter a series of framed statements, the eponymous short fictions. All are fragments, miniature narratives that describe a seemingly meaningless moment full of possibility even though it never reaches closure. A man in work clothes massages the walk button at an intersection; an older tourist tries on an overpriced beret in a shop in Spain; a woman smokes one cigarette after another and never sips her drink. You get the impression that you are entering a very specific, subjective space. The stories and scenes presented here are grounded in the artist’s personal experiences and filtered through his private and particular sentiments, yet they speak of the kinds of things we have all encountered.

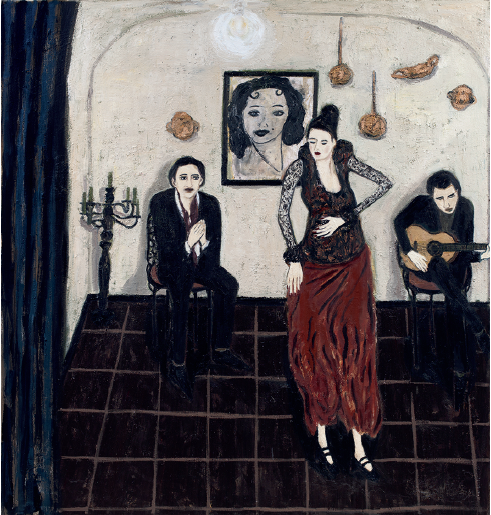

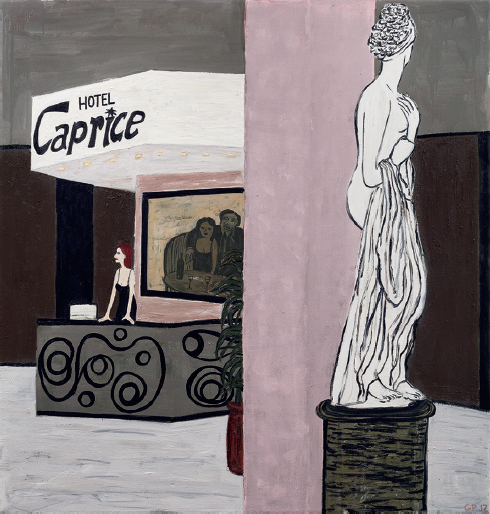

Beyond these framed fictions is a large room filled mostly (though not entirely) with stunning paintings of darkened nightclubs, as in Honky Tonk, 2017. Well-painted but awkwardly drawn drinkers variously console themselves or gather to debate jazz, smoke or whisper sweet nothings. If you know your art history, these works evoke everything from Edgar Degas’s L’Absinthe, 1875–76, to the highly expressionistic Cocktail Party Three, 1967, by Maxwell Bates. However, where Degas’s work is naturalistic and Bates’s is stridently coloured, Pearson’s is dark, even foreboding, and more pointedly “northern expressionist” than either Degas or Bates (think Edvard Munch). Curator Liz Wylie tells us in the catalogue that the catalyst for this theme was Pearson’s experience of a Diana Krall concert in Berlin in 1998. Prior to this moment, Pearson practised what he called “symbolic abstraction,” conceptually related to the work of Jack Shadbolt, but darker and moodier. After Krall the works retained the gloom but became more representational, with dominant earth tones and deliberately inelegant, attenuated bodies reminiscent of Bates’s or even of El Greco’s Mannerist works, like The Vision of Saint John, 1608–14. Distributed among these paintings are small video installations that offer vignettes, like the short fictions at the entrance. In one Pearson presents four scenes of drinkers conversing with a bartender; in another he offers variations on the old gag about “a fly in my soup.” There is, in all of them, a kind of deliberate videographic awkwardness that corresponds to the ungainliness of the painted figures. All the works offer crumbs of conversations that lead nowhere.

Gary Pearson, The Flamenco Dancer, 2014, oil and oil enamel on canvas, 203 x 193 cm. Collection of the artist. Images courtesy Kelowna Art Gallery.

At first viewers unfamiliar with expressionism might not quite grasp what’s happening. Pearson has chosen to present the world from a subjective perspective, altering forms to express emotional resonances instead of physical appearances. The context explaining the artist’s intellectual effort behind this exercise emerges unmistakably in the beautifully presented and very well-illustrated catalogue accompanying the show. There, four essays and a thorough chronology clearly place the artist in the category of artist-as-thinker. This develops particularly well in the extended conversation between Pearson and former Kelowna Art Gallery curator Ihor Holubizky, now senior curator at the McMaster Museum of Art. The themes include Pearson’s use of photography as an aid in composition; why a painter would engage video; and how Pearson incorporates in paintings and videos alike a kind of alienation affect and narrative suspension that derive from the plays of Bertolt Brecht and Samuel Beckett.

Regarding photography Pearson explains that he has been haunted by particular images for decades, citing as an example a photo of an anonymous couple in a tavern booth that certainly informed Café Blues, 1979. Holubizky delves deeper, suggesting that Pearson’s Girl and Dog, 2014—itself a non-barroom image—is more interesting than the photographed street scenes in Leeuwarden that he composited in the painting. If nothing else, this painting makes me realize just how close to the work of Jeff Wall these paintings are, despite their obvious differences in appearance. Pearson himself suggests this.

Hotel Caprice, 2017, oil, oil enamel and polyurethane on canvas, 203 x 193 cm. Collection of the artist.

Objectivity is less interesting than the artist’s subjective responses to it. This can’t be achieved in the same way through video, so Pearson turns to Brecht’s Verfremdungseffekt, which Brecht himself described as revealing the artifices of the theatre in order to block “the audience … from simply identifying itself with the characters in the play. Acceptance or rejection of their actions and utterances was meant to take place on a conscious plane, instead of … in the audience’s subconscious” (John Willett, ed. and trans., Brecht on Theatre [New York: Hill and Wang, 1964], 91). In the videos the performances are stiff, drawing attention to the fact that they are merely running scripted lines. Meanwhile, other artifices, including the artist in the background, ensure that viewers are slightly “put off,” provoking the Brechtian estrangement effect. At the same time the pointlessness of the stories themselves ensures that we are forever expecting another narrative moment that never appears, as in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

The other texts in the catalogue include a foreword by writer Michael Turner, curator Liz Wylie’s splendid and thoughtful survey of Pearson’s career and a shorter meditation on what it was like to be a fledgling writer in the Okanagan by Aaron Peck, now a well-established critic living in Brussels. Together, the show and its catalogue are a significant contribution to our understanding of the work of an important artist who richly deserves critical and popular attention. ❚

“Short Fictions” was exhibited at the Kelowna Art Gallery, Kelowna, BC, from January 20 to March 18, 2018.

Robert Belton is an associate professor of the history of art at the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan Campus. He is the author of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo and the Hermeneutic Spiral (2017), Sights of Resistance: Approaches to Canadian Visual Culture (2001), The Theatre of the Self: The Life and Art of William Ronald (1999) and The Beribboned Bomb: The Image of Woman in Male Surrealist Art (1995).