“Frontrunners”

“Frontrunners,” curated by Cathy Mattes, had two incarnations. An exhibition of Alex Janvier’s works filled one exhibition room at Plug In ICA; at Urban Shaman there were representative works by members of the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. (PNIAI), formed in 1972. This work was paired with that of artists who have inherited their mantle. It’s bravo all the way round. The two exhibitions were mounted at the conclusion of the multi-venued, year-long “Close Encounters,” which focused on contemporary Aboriginal art and was funded largely by Winnipeg Cultural Capital of Canada 2010. The opportunities to define future trends, establish cultural inheritors and mockers, consider indigenous artistic practice from inside and outside the country, and dream creatively about the future are rich and plentiful.

Founded in Winnipeg by the venerable genius Daphne Odjig, the PNIAI included the artists Alex Janvier, Jackson Beardy, Norval Morrisseau, Eddie Cobiness, Carl Ray and Joseph Sanchez. With a will to transform and empower, their work sustained a vision, challenged the status quo and depicted spiritual premises and suppressed relationships. Odjig explained they were seeking collegial support, a market and patrons.

Alex Janvier, Sun Shines, Grass Grows, River Flows, 1972, acrylic on canvas. Photograph: Jaya Beange. Image courtesy of Plug In ICA, Winnipeg.

At Plug In, there were just enough Janvier paintings from the last five decades to whet the appetite for a fuller treatment and to harken back to curator Lee-Ann Martin’s exhibition in which the foundational scholarship and conceptual analysis of this Cold Lake, Alberta, artist’s development and works were laid. Just enough paintings here, indeed, to marvel at the myriad of potential intersections and themes within his life’s work: the excursus on the circle, for example; the ellipse and the hyperbola in its mathematical and didactic forms; the deeply rooted feeling, understanding and view of land and space; and the ongoing assaults by corporation and state on Indian land. Janvier left the Indian Group of Seven, as it is sometimes called, after a few years of membership. His work has been, perhaps, the least understood of the artists of his generation. It was this group that set the terms for a contemporary art that honoured tradition and forged new iconography, that insisted on equality and opportunities with mainstream Canadian artists while the pains and trials of colonial policies, residential schools and ’60s Scoop babies were all still fresh.

In Plug In’s rectangular exhibition space, the early canvases declare Janvier’s brilliance at forging a distinctive style that related to Morrisseau’s Woodlands iconography but diverged in ways that let in the Modernist and traditionalist idioms. I am very fond of the early work, with its taut nexus of jewelled colour, oscillating negative and positive spaces, and the best use of white this side of Ron Bloore. But there is more. Janvier invests psyche and doubt into the work; he explores land and politics and, in the larger paintings, moral instruction and outrage. The bright orange Lubicon makes an appearance, recalling the complex position of contemporary Aboriginal art, the politics of display and sponsorship, and the ongoing dialogue assumed by Aboriginal curators, art historians and others to sort out these issues. The long works illustrate his penchant for the wall mural and public installation, a genre where he had both soared and suffered.

Daphne Odjig, Flack, 1973 (left); Jackson Beardy, Flock, 1973 (centre); and Jackie Traverse Niizhwaaso/swi, 2011 (right). Installation view of “Frontrunners” at Urban Shaman Gallery, 2011. Photograph: Kevin Lee Burton. Courtesy the Urban Shaman Gallery, Winnipeg.

While capable of extremely hermetic work, perhaps of all the seven, Janvier was and is the most interested in the vast view. His cultural contributions remain active and renewed as he engages with younger artists in collaborative paintings; for example, this year at the street-front arts centre, Ndinawe, as part of “Close Encounters” events. Really, who wouldn’t want to paint with Alex Janvier?

The exhibition at the Urban Shaman Gallery was intended, as Mattes noted, to “expose the impact of the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. in Manitoba…a starting point for discussing the history of artistic and social change.” The impact of the group has been mapped out elsewhere by Robert Houle, Elizabeth McLuhan, Colleen Cutschall, Bonnie Devine, Gerald McMaster, David Garneau, Lee-Ann Martin and many others, and the Urban Shaman show took a decidedly localized spin. Mattes included works by all members of the group and, as she has suggested, contemporary claimants to the tradition. “Frontrunners” at Urban Shaman included work by four contemporary Winnipeg- based artists: Lita Fontaine, Louise Ogemah, Darryl Nepinak and Jackie Traverse. Significantly, for a show about dissemination and cultural connections, all four work with youth in various programs in addition to their studio practices. The history of Urban Shaman and those instrumental in giving foundational blood, sweat and tears—by refining and shaping its collective vision for a community-based Aboriginal artist-run centre—have been honoured through this selection of “Frontrunners.”

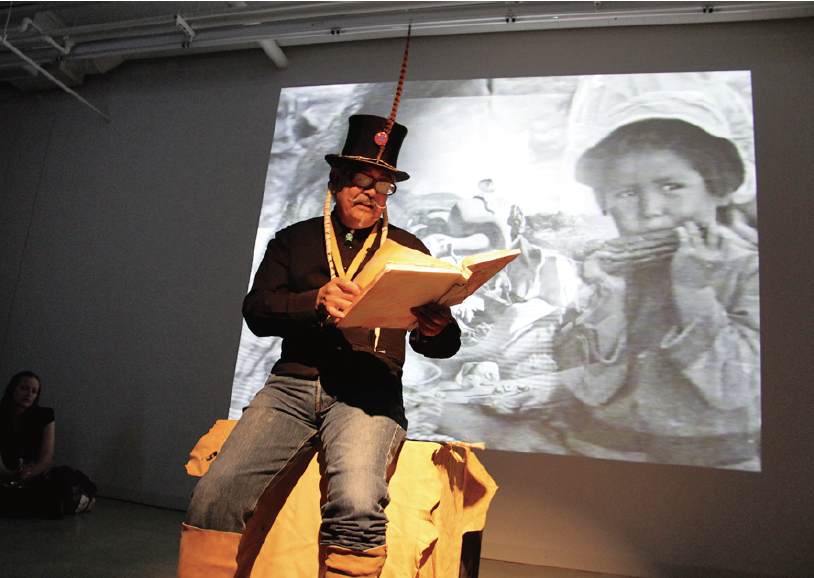

Performance at Opening Reception of “Frontrunners.” Joseph Sanchez, “Listening to our People over the Rhetoric of the 21st Century,” May 28, 2011. Photograph: Jaya Beange. Image courtesy of Plug In ICA, Winnipeg.

Mattes scored a curatorial coup in obtaining important loans of Odjig, Morrisseau and Beardy works. Some we have seen recently in retrospectives and thematic shows elsewhere across the country. The point here was to acknowledge, celebrate and allow for closer inspection. In this way she positioned an iconography that threatens to free-float without ground over the wall murals and art cards of multiple public spaces. Artists Ogemah and Fontaine were instrumental in shepherding the organization in its up-and-down early years, much in the same way that Odjig catalyzed artists in the 1970s. On display are Lita Fontaine’s parfleche and parfleche paintings, Ogemah’s wood carvings, Traverse’s comical paintings and Nepinak’s work in film. Younger artists Traverse and Nepinak have enough distance from the frontrunners to exhibit a little cheekiness with a nod. Fontaine returns to her innate sense of colour, feminist proclivities and investigations of tradition in the parfleche work. Ogemah often changes media. He has combined canvas and rock, or fur hide and painting. Some of his earliest work paired photographs of his mother’s residential school experience with birch bark. That show was held long ago in the dank basement space in the Exchange that was Urban Shaman’s first home, a reminder of how successful and significant the gallery has become. A generation and a half later, one can see the huge contribution, positive impact and magnetic effect Urban Shaman has had and continues to have in the community—bringing in important curators and artists from across the country, embracing new media, supporting emerging and mid-career artists and creating a dialogue that interrogates the mainstream and the role of tradition.

Both the Janvier show and this group exhibition are apt animations for this historical moment of reclamation, assertion and re-imagination of forerunners and their sometimes wayward progeny. ❚

“Frontrunners” was exhibited at the Plug In ICA from May 28 to July 24, 2011, and at Urban Shaman from to May 7 to July 17, 2011.

Amy Karlinsky is a Winnipeg-based writer.