“Frontera: Views of the U.S.-Mexico Border”

Borders are nowhere, and borders are everywhere. They can be constructs or they can be ever so real. We live in an era of intense migration, often the result of war, and borders are the flashpoints that awaken our awareness of the global issue of migration. Witness Ai Weiwei’s _Good Fences Make Great Neighbors_Borders are nowhere, and borders are everywhere. They can be constructs or they can be ever so real. We live in an era of intense migration, often the result of war, and borders are the flashpoints that awaken our awareness of the global issue of migration. Witness Ai Weiwei’s Good Fences Make Great Neighbors, an evolving New York initiative expected to take many shapes and forms, notably the Gilded Cage in Central Park, comprised of a series of turnstiles. And this autumn on the Mexico-USA border, the French artist JR produced an immense image of a Mexican boy on the border in Tecate, southeast of San Diego, looking out into the USA. JR addresses a political ambiguity, just as he did in Palestine with wall photos of the faces of Jews and Palestinians next to each other. The artist/photographers in the “Frontera: Views of the U.S.-Mexico Border” exhibition likewise address issues of identity, of homelessness, of what border lines signify. “Frontera” is timely, given America’s ambiguous situation regarding the wall between Mexico and the USA. Can a country without immigrants really be a country at all?

Geoffrey James, Looking towards Mexico, Otay Mesa (also titled, Partial View of the United States-Mexico Border with Otay Mesa, San Diego County, in the foreground and Mesa de Otay, Tijuana, in the background), 1997, gelatin silver print, 76.3 x 84 cm. CMCP Collection, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Photo: MBAC. © Geoffrey James.

Geoffrey James’s photographs adhere to a certain photo aesthetic of beauty, but convey a sense of the environments in which he is photographing. With James, it is as much the absence as the presence of people that gives us a sense of psychic borders, of the border as a construct that is striking. We see wall sections of it disappearing into the coastal waters, or a section of metal fencing close up that extends off to the horizon line. Only one tree and a road demarcate it all. A photo of makeshift temporary huts with plastic tarps is nonetheless a memory of the migrants who passed and will pass through the place to disappear. Alejandro Cartagena’s photograph of his daughter behind an actual grid-like metal section of the border wall makes the wall feel like a prison. It’s a powerful symbol of what walls can do to dehumanize what makes us all human. We cannot see the girl with any clarity; her persona is overprinted by the rusted metal fencing. Which side of this “wall” construct is the prison? Borders and frontier lines are metaphors for the human struggle for acceptance, or containment, but they are never effective in stopping smuggling or migration.

Mark Ruwedal’s photos speak with a visual directness of the uneasy pain of migration and displacement. In Crossing #14, 2005, we see a Guatemalan passport discarded, an afterthought, next to a desert shrub and plastic bottle, all speaking to the expendability of human rights and identity. With Crossing #6, 2003, plastic bottles are all that remain, austere and ironically disposable witness to the endless chain of undocumented people. Like a post-anthropological message in a bottle, these “clues” embody transience.

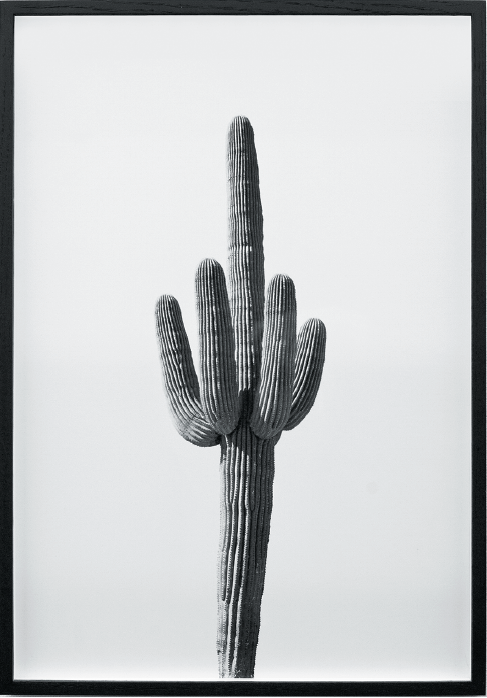

Adrien Missika’s stark cacti photograph series “We didn’t cross the border the border crossed us,” 2014, have stark, anonymous white backgrounds and look denatured. Like specimens from the ecosystem, these cacti symbolize the continuity of nature beyond, regardless of borders. Covering an entire gallery wall, Missika’s As the Coyote Flies, 2014, presents a dizzying array of displaced imagery: truck tire tracks in the sand, electricity wires and scenes of a have-not border town with a background of sound build an atmosphere of disorientation.

Adrien Missika, We Didn’t Cross the Border, The Border Crossed Us, 2014, photograph, 49 x 39 x 3 cm. Photo: Adrien Missika. Courtesy Galerie Bugada & Cargnel, Paris. © Adrien Missika.

Pablo Lopez Luz’s overview of the landscape on the borders expresses something of the ecology of the land, peopled at times in towns; other times, simply mountainous or desert-like. We can see the grid-like arrangement of private property, or the city street patternings, from afar. The enduring character of the land, some sections full, others empty, becomes a metaphor for the human presence or absence, with its strain on resources. As Kirsten Luce says, “My goal is to create pieces that inform a wider audience, but which my colleagues and law enforcement on the border will see as accurate and timely.” Luce’s photos put their finger on the trigger of this crossing point where “wetbacks” and drug traffickers intersect unintentionally. A photo of “wetbacks” crossing the muddy green border by the river gives a sense of how it really is for so many people; these are nomads by necessity.

Ranging the breadth of the exhibition space, Daniel Schwartz’s accordion-like assemblage of a Google map provides a stunning overview of the US-Mexico border, arranged in two lines or sections. Like satellite mapping, these scenes are estranged. At either end of the images of deserts, towns, cities and rugged terrain, there is the blue ocean salt water. These assemblages can fold out and be seen, or they can fold up and be carried, migratory objects themselves. Such is the ephemeral nature of photography and photographers who, like Sebastian Salgado, have covered the tragedies of war and migration in the past. The photographers in “Frontera” are witness to this ongoing mass migration, and present a wellspring of viewpoints on this endless border-crossing phenomenon. As photographers, they, too, are nomads by necessity, suited to address the border-crossing theme. ❚

“Frontera: Views of the U.S.-Mexico Border” was exhibited at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, from November 3, 2017, to April 2, 2018.

John K Grande’s latest book is Art Space Ecology: Two Views—Twenty Interviews (Black Rose / University of Chicago, 2018).