Fresh Blood

The Main/Access Gallery, located in the newly renovated Artspace building, seems unlike most of the alternate galleries in the city. It’s new and clean; it lacks the cachet of creaking floors and dusty windowsills. But the opening of Fresh Blood demonstrates that in the most important ways it is similar to its radical gallery cousins. It’s hot—up-to-the-minute hot—with a show of young new artists and a young hip crowd dressed mostly in basic black. And it’s hot—stultifyingly humid and warm—because Main/Access on this blazing June night has no airc-onditioning. (Young artists get a lot of support in Winnipeg, as Artspace proves, but they don’t get air-conditioning until they move on to the Winnipeg Art Gallery.)

But absence of coolness aside, what does the show have to offer? Many of the works in Fresh Blood, a five-artist show curated by Wayne Baerwaldt, hinge on the problem of scale. In this sense John Groves’ piece, Flower, is a keynote; it is about scale. A large—really large—flower, it looks like a kid’s papier-mâché project transformed by B-movie technology into something huge. It’s at once goofy and monumental. This piece demonstrates very economically that all you have to do is change the scale, and that will change everything.

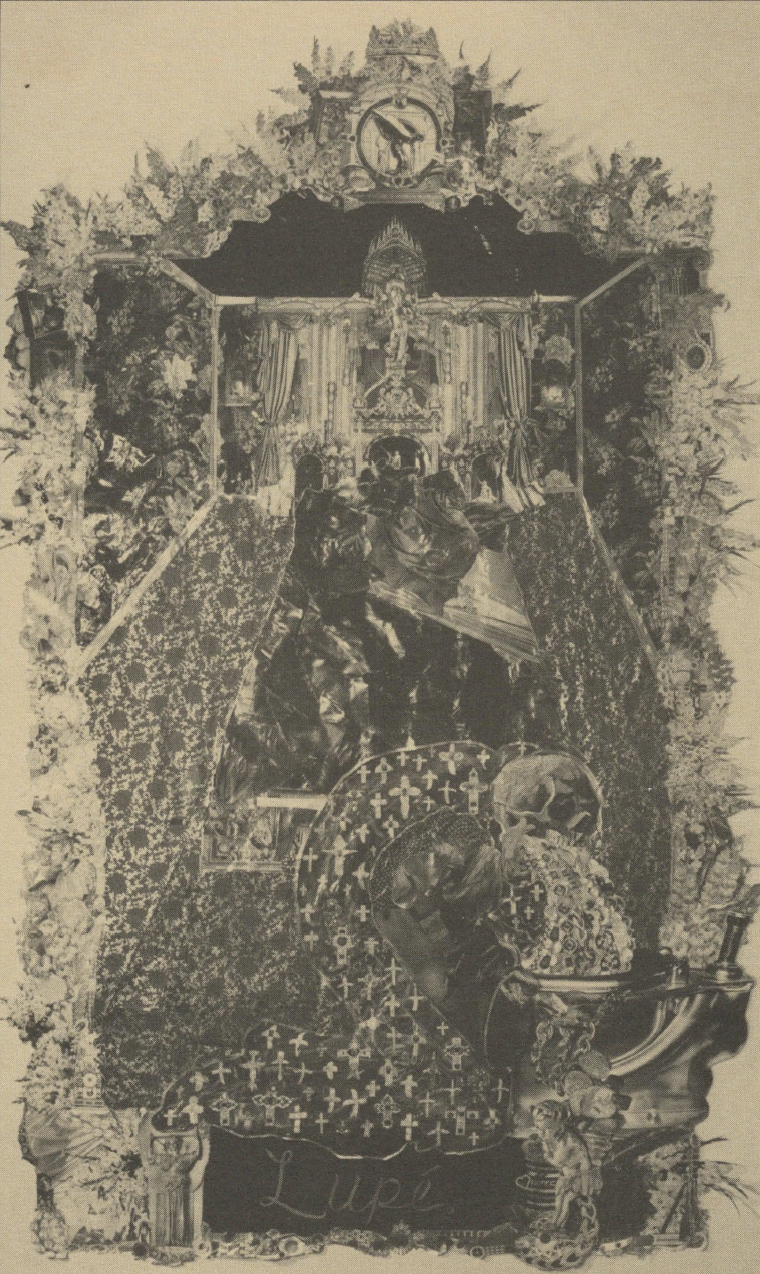

Marnie Hilash, Lupe, collage, acrylic, 1986. Photograph by Leonard Schlichting.

This principle is explored, at the other end of the spectrum, by the works of Andrew Beck. Beck’s sculptures are small and ingenious. There is something wonderful about the way they seem needlessly complicated and detailed, and this meticulous construction is even more incredible when you consider that Beck works in metal. One piece features a small replica of classical temple architecture and a teetering edifice of stairs and platforms, complete with a hanging noose and a trap-door operated by a switch placed next to a small chair. The whole thing is less than a metre high. The time-consuming construction of Beck’s work—the sheets of metal carefully layered, jagged edges painstakingly cut, fiddly elements soldered—is often completely denied. The works exhibited on the lower level of the gallery seem, at a distant glance, to be made of papier-mâché, maybe ceramic: they are gaudy, candy-coated, colourful, sometimes primitive, sometimes garishly Pop. The works upstairs are more obviously metal—there is a resemblance to rusting farm machinery—but they are also complicated, with intricate ornamental bases and complex networks of braces and supports. One work, a Pop evocation of the American west and violent death, shows a tilted road supported in the air on fragile legs, as well as a billow of white metal cloud hanging over a splashy car that is the end of the road and the beginning of an abyss. Beck’s work is a witty combination of scale and material. He has taken metal, so closely associated with those large, abstract, public sculptures that people write to the editor about, and used it to make small, clever and sometimes exuberant personal pieces. Beck takes on large themes, but his works are not imposing. Unlike the immediate hard impact of large-scale minimalism, the delicate scale and detail of these pieces reveal themselves slowly—they are wonderfully weird little worlds to be examined minutely, carefully.

Marnie Hilash’s works also turn on scale—on the balance between the large scale of her own created images and the tiny scale of the found images they contain. Her four collages make a remarkably extensive and consistent statement about the complex interactions of consumerism, sexism, religion and spectacle. Her works draw their raw material from glossy magazines—pictures of jewellery, watches, furs, painted lips and hands. Hilash rips these images from their cool, smooth, opulent magazine settings and pastes them up into a confusing, messy, extravagant glut, showing them up as the consumerist wet-dreams they really are. This impression of disturbing variety and plenty—a concentrated vision of advertising overkill—is balanced, however, by Hilash’s own structures. Her collages are not random arrangements; she re-forms the magazine material into her own images: a Marilyn Monroe icon teasingly holds down a swirling white skirt moulded from pictures of “a girl’s best friend,” diamonds, pearls and the traditional trade-offs of sexual favours; a beautiful woman is crucified, her robe made up of the conventional images of the female—vamp, victim, unobtainable prize. The cohesiveness of Hilash’s formed structures is in careful tension with the inchoate, tiny images that make them up.

Andrew Beck, Soul in the Middle, welded steel, polychrome, 1987. by Leonard Schlichting.

Meg Cullen uses scale to create a landscape that is entered, not observed. One work, made of rough-edged slabs of overlapping paper and canvas, subtly evokes a lush, wet jungle of plants, rocks and water. The work is formal; Cullen’s material is palpably material—heavily painted, rough and flat. At the same time, the work creates a very atmospheric imaginary world, a dangerously fertile, mysterious and primitive place. The large scale of the work and its unframed and irregular edge combine to suggest the jungle may just keep growing. It threatens to overwhelm, pleasantly.

Dale Boldt, in contrast to the other artists in the show, works within the tight restrictions of wall painting. Her acrylics may seem at first to be conventional abstractions—and good ones—with an inspired use of colour. But there is something excitingly organic and dynamic in the large, orange flashes of colour in one work; they are like sparks from a fire, magnified and captured for a brief second before they transform. These neatly framed paintings contrast with Boldt’s large, unframed, pastel and chalk works. Here she is working with scale, in a sense blowing up a drawing that uses low-key materials and simple organic emblems (birds, beasts) to a scale associated more often with stunning public pieces, like her acrylics. Hung on two opposing walls, these two sets of works reflect and expand on each other.

I suppose that group shows, especially of young artists, lend themselves to sweeping conclusions about the directions of art. Curator Wayne Baerwaldt has not looked for any easy answers in bringing together five very different artists. I think he is right to view these works as examinations of “the effects that the transformation of an image can have on meaning.” If young artists can be said to share any concern in these very eclectic days of post-modernism, it is the search for a way to work through representation. These artists want to use images, but they are distrustful of straightforward representation. The result, in an exhibition like Fresh Blood, is imagery stretched out or shrunk, media conventions transgressed or parodied, works obviously formal but also meaningful. Groves’ giant flower, Cullen’s powerfully hulking landscape and Beck’s little carnivals are all evidence of a new approach to representation, evidence of fresh blood in the Winnipeg arts community. ♦

Alison Gillmor regularly reviews gallery exhibitions for Border Crossings.