Fred Herzog

“I can’t believe that’s all spontaneous,” said the guy standing next to me at the Fred Herzog show. He gestured toward Chinese New Year, Vancouver, 1965, a panoramic colour photograph of a crowd of people watching a Chinatown parade from a line of upper-storey windows decorated with flags. Remarkably, it compresses within its margins a wealth of human expression, of age, gender and dress, of architectural detail, civic history and cultural sentiment.

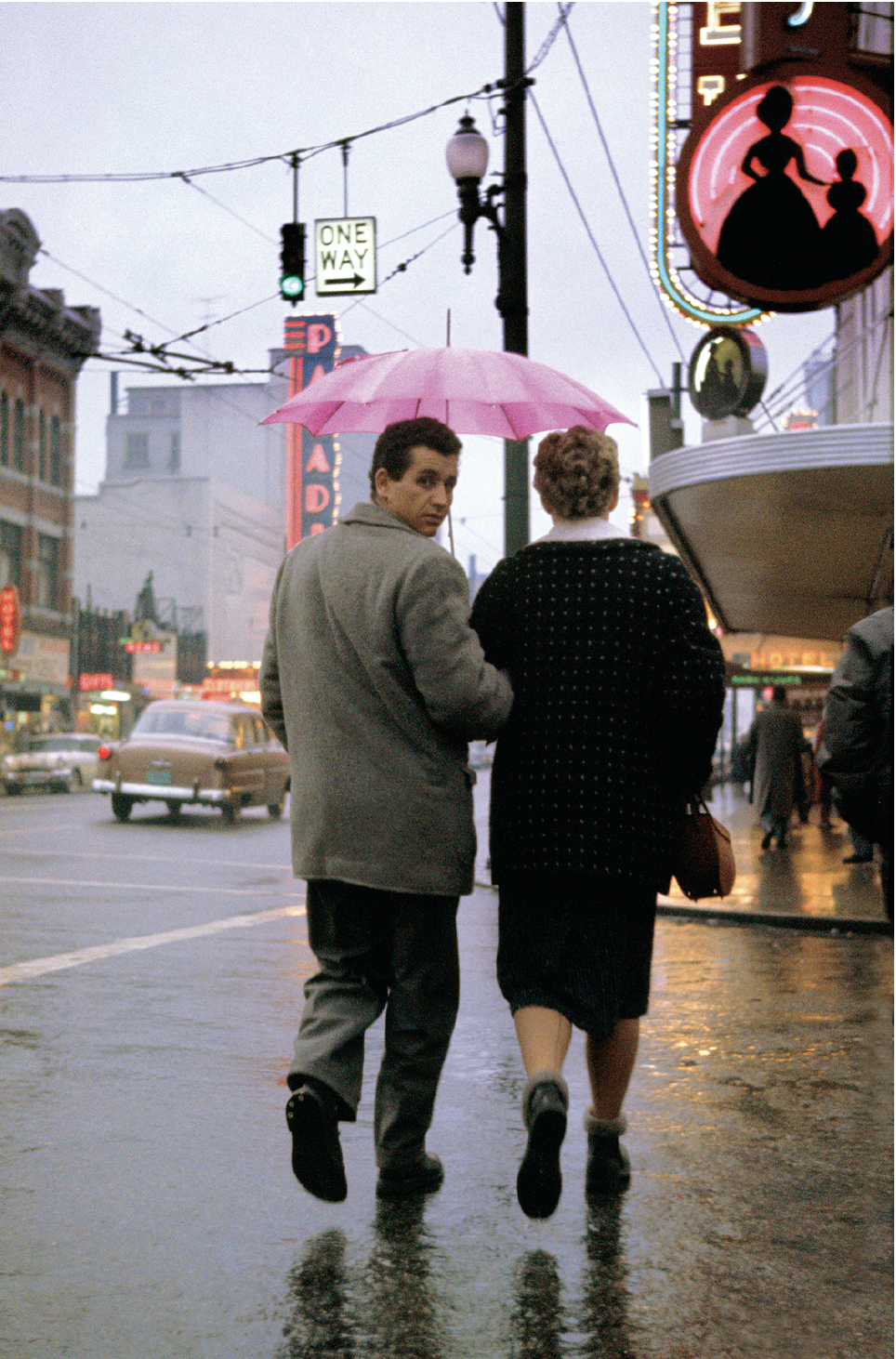

Most of the work on display in “Fred Herzog: Vancouver Photographs” was shot on Kodachrome slide film during the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, giving it, as the show’s organizers have pointed out, a considerable clarity and tonal range. Giving it, too, a frozen-in-time mood. Many of the images are street scenes, sometimes thronging with pedestrians enjoying an evening out, at other times deserted in the thin light of morning. Herzog pointed his camera at intersections, movie theatres and low-end storefronts, at corner grocers, junk shops, barber shops, and windows crammed with pulp fiction and girlie magazines. He also shot back alleys, fairgrounds, gaming arcades, rooming houses, parking lots, concession stands, billboards and neon signs. Lots of neon signs, glowing red, orange, green and blue against a nighttime drapery of rain and darkness.

The selection of works on view in this show suggest that the upperclass urban experience was of no interest to him. Neither was the Arcadian landscape. There are no mansions with big trees and broad lawns here, no golf clubs, tennis courts, well-groomed parks, statuary. No neo-classical banks, courthouses, government offices. No debutante balls in imperial hotels, either. The life of the street, whether downtown or on the East Side, the quirkiness of marginal enterprises, the ubiquitous intrusion of the car into post-war existence and the clamour of commercial signage, these are some of the themes Herzog has threaded into his study of Vancouver.

During the early decades of his career, Herzog’s favoured means of exhibiting his work was through slide presentations (colour prints being so uncertain at the time). Recently, however, his slides have been digitized so that they can be shown (and sold) as inkjet prints. Very handsome they are, too. In the unusual case of Chinese New Year, computer technology was also used to morph two or three individual images into a single panorama. Otherwise, yes, it was completely unposed—a classic street photograph in the mid-20th-century Modernist tradition. It has something in it of Robert Frank (think of his Parade, Hoboken, New Jersey, 1955), something again of Walker Evans, both of whom Herzog acknowledges as influences.

Fred Herzog, Main Barber, 1968, inkjet print. Collection of the artist. Courtesy Equinox Gallery, Vancouver.

Still, that ardent viewer’s comment about spontaneity indicates how conditioned we are by the postmodern practice of staging elaborate scenes and tableaux for the camera, rather than catching real-life human drama as it naturally unfolds. Attitudes towards the nature of representation have shifted radically, of course, as has belief in the verity of the photograph. Formalist preoccupations have been usurped by social ones, the fictional has superseded the documentary function of the camera, and, at this point in history, it’s difficult to disburden Modernist art of postmodern judgements and expectations.

Not incidentally, the Vancouver Art Gallery was concurrently hosting “Acting the Part: Photography as Theatre,” a National Gallery of Canada survey of both small historic and large contemporary staged photos. Occupying the VAG’s entire main floor, “Acting the Part” served as the ideological counterbalance to Herzog’s work, although I couldn’t help thinking that it was also meant to establish where the gallery’s true curatorial commitments lay.

Herzog, who was born in Germany in 1930 and whose youth there coincided with the grim war years, arrived in Canada in 1952, a classic outsider, initially reeling with culture shock, mostly having to do with the urban architecture he encountered. After a year in Toronto (a place he found ugly and unappealing, he says, “because I had not yet learned how to turn ugly scenes into beautiful pictures”), he settled in Vancouver, and began taking what would become tens of thousands of colour photos of the place. (For much of his career, he supported himself as a medical photographer and, as a side interest, he also took acclaimed images of live butterflies. Still, Vancouver has remained his most enduring subject.) At the show’s media preview, curator Grant Arnold suggested that the remarkable breadth and depth of Herzog’s record of his chosen city is unique in Canada. For years, however, his work was rarely exhibited, and was known only within a small coterie of artists and photographers.

It’s intriguing to see how Herzog anticipated aspects of concept-driven work in his medium, and particularly the Vancouver School of photo-based art. His commitment to colour in the 1950s was unusual within the context of fine art photography, then wedded to the black and white aesthetic. Indeed, Herzog’s choice of colour, mated with unglamourous subjects in the built environment, foresaw Stephen Shore and others in the New Topographics movement, just as it did generations of Vancouver artists, from Iain Baxter and Roy Arden to Howard Ursuliak and Evan Lee.

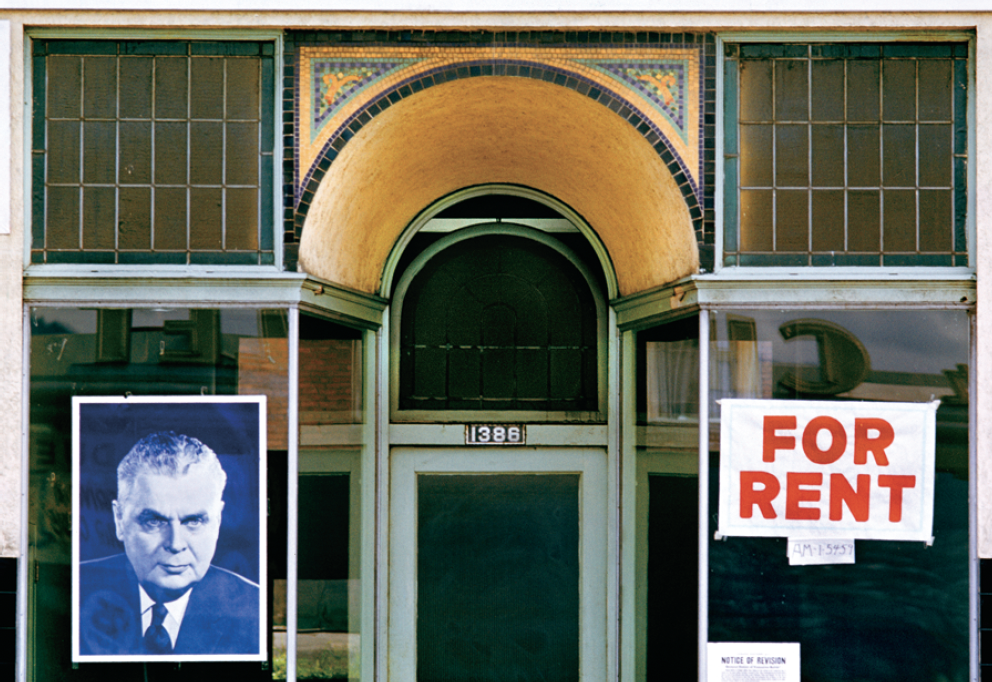

Fred Herzog, Diefenbaker, 1962, inkjet print. Collection: the artist. Courtesy Equinox Gallery.

As Arnold notes, Herzog assumed the role of flâneur, walking the city streets, observing his surroundings and the behaviours of his fellow creatures. Again, the Baudelarian idea of the flâneur, as meditated upon by Walter Benjamin, was embraced by subsequent photo-based artists, including Jeff Wall, Ian Wallace and Christos Dikeakos. Arnold points out, however, that conceptual photographic projects undertaken by Wall and Dikeakos in the 1970s, while also depicting overlooked aspects of the urban environment, were shot from moving cars, so that the car itself became “the imaging device.” This, he writes in the book accompanying the exhibition, sets the younger artists’ methods apart from Herzog’s practice.

Indeed, most of Herzog’s photos were taken on foot. Still, there are a few early, anomalous, black and white images in the show (tucked nearly out of sight behind a wall near the elevator) that are obviously shot from inside a car. Dunlevy at Powell, 1970, and Hastings at Carroll, 1971, both employ window frames, dashboard and rain-splattered windshield as an extra enclosure around Herzog’s lens, so that his car functions as both context and supra-camera. His vehicle isn’t moving (it’s either parked by the side of the road or stopped at a traffic sign or signal), but it is still an imaging device and, for that reason, predictive.

Automobiles—actual and depicted in advertising, brand new and bespeaking a dream of prosperity and mobility, junked and dismembered in a vacant lot, signalling the loss of that dream— are a preoccupation of Herzog’s, reflecting again his outsider status and the wonder he brings, as a transplanted European, to his North American subject. Other peculiarities of place include a big cigarette ad painted on the side of a clapboard building; a shop window filled with bottles of Orange Crush, 7-Up and Coca Cola; and sidewalk vendors in Chinatown. There’s also Paris Cafe, 1959, with two plastic Pepsi Santas and a miniature silver Christmas tree set in the window, along with faded, handwritten signs proclaiming “MEAL TICKETS,” “CHINES – DISHES” and “LOOK OUR SPECIAL MEALS EVERYDAY.”

Again, Herzog’s work reveals his fascination with the flamboyantly commercial fabric of Vancouver, along with this city’s particular blend of Asian and European influences. Granville Street and Hastings Street lit up by sign upon sign of dazzling neon— Vogue, Plaza, Paradise Theatres, C. Kent Custom Tailor, White Lunch Cafeteria, Brown Bros Florist— also speak of a considerable optimism and individuality, upon which both Herzog and Arnold have remarked. Herzog particularly laments the disappearance of distinctive signage (much neon was eliminated by Vancouver’s city council in the 1960s and is now lost) and individual, hand-altered façades and display windows, replaced by tedious miles of the most bland and banal retail frontage. As with most North American cities and towns, big-box stores, retail chains and faceless shopping malls have supplanted the small businesses that once lined Vancouver’s streets.

Fred Herzog, Untitled, Granville Street, 1960, chromogenic print. Collection: Vancouver Art Gallery. 41809p001t116.indd

Herzog’s regret for what has been lost is a clue to the heightened air of nostalgia that pervades his show. When viewers weren’t declaiming to me about the spontaneous versus staged nature of the work, they were pointing out the restaurants and movie theatres they’d visited as children. A persistent exercise while viewing the show has been remarking on how much Vancouver has changed: Herzog’s 1957 shot of the West End from the Burrard Street bridge shows the area startlingly low-rise. The neighbourhood then comprised block upon block of wooden houses, now supplanted by high-rise apartment buildings and condominium towers, granting it status as one of the most densely populated residential areas in North America. False Creek, as seen by Herzog in the ’50s, was an active industrial site, filled with fishing boats, log booms, lumber mills and warehouses. Now, it is the location of chi-chi townhouses, more glass-walled condos, and upscale shopping and dining venues.

Herzog also mourns the loss of the public’s commitment to dress in something other than blue jeans. His photos show us that during the 1950s, even in the most casual of circumstances, men wore hats, ties and jackets, and women, dresses, nylon stockings and high-heeled shoes when they went out. “When people dress up, they show pride and respect for each other,” Herzog said at the preview. Although society is better off economically, he continued, “Vancouver has not been enriched in culture and conviviality.” Perhaps this reactionism and sense of loss explain the sparseness of his images of Vancouver from the 1980s forward (it’s hard to know, given how many thousands of Herzog’s images were not on view): there was less and less here to catch his mid-20th-century eye. Unlike Roy Arden, for instance, Herzog is not driven to make art out of a suburban landfill site or the interior of a Wal-Mart.

Documenting cultures and ethnicities other than his own is another anachronistic aspect of Herzog’s oeuvre, given that the politics of representation and the idea of cultural appropriation have been so fully absorbed into the postmodern lesson. There are shots here of Asian-Canadians in Chinatown settings, as well as in gaming arcades at the Pacific National Exhibition. There are also images of First Nations children and families, playing games, sitting on a porch and attending a powwow in North Vancouver. In the sense of the photographer’s privilege as a middle-class white male of the 20th century, however, I wonder what the philosophical difference might be between Herzog’s 1959 powwow images and Jeff Wall’s 1986 The Storyteller, with its First Nations characters encamped on a desolate patch of land beneath the Georgia Viaduct. Has Wall any greater right to possess the narrative of his staged photos than Herzog has to his carefully chosen record of actual events? It’s a difficult subject, still unresolved. As with literature, fiction and nonfiction are simply different ways of getting at some notion of the truth. ■

“Fred Herzog: Vancouver Photographs” was exhibited at the Vancouver Art Gallery from January 25 to May 13, 2007.

Robin Laurence is a writer, curator and a contributing editor to Border Crossings from Vancouver.