Francis Alÿs

Wandering through a public gallery or else through the centre of some vast city—Mexico City, yes, but equally São Paolo, Venice, Istanbul, Los Angeles—locals and tourists alike have, since the early 1990s, come across the bent frame of a man standing, always at angle, a reed against the wind, looking up, walking, painting signs, carrying a gun, pushing a block of ice, herding sheep: uncanny actions, strange yet weirdly familiar, refashioned rituals of ordinary life.

I recall last summer encountering the frame—in the guise of those actions real and imagined presented by the Mexican-based Belgian artist Francis Alÿs—amid the throngs in the box-like galleries of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. I remember the crowds and the walking and the way the shudder of the massive video projections gave a sense that the walls were shaking, and not just the walls but the building too, as if the whole thing—the push and shove of us consumers, the global markets, modernity itself—could collapse and leave us in a swirl of dust, at the centre of a tornado, but somehow it would be OK. “Maximal effort, minimum results,” Alÿs has said of his work’s ultimate aim.

Francis Alÿs (in collaboration with Honoré D’O), video still from Duett, 1999, video (colour, sound), 6 minutes, 48 seconds. Courtesy the artist.

In one gallery stood an old projector looping an animated image of a girl pouring water from one glass to another and back [Song for Lupita (Mañana), 1998] while a record player spun the song repeatedly and the many small paintings lining the surrounding walls engulfed us in miniature. “Le Temps du sommeil,” an ongoing work that the artist began in 1996, played head games as tiny, lightly sketched figures rendered in browns, rusts and olive tones seemed to enact curious scenes in no particular order. Here, a suited man walks away wearing an odd, bunny-eared hat; there, fire engulfs a boat on water; elsewhere, a man stands with a box on head, a dog at his coat. It’s a game or a riddle, a catalogue of eccentric moments that’s less a permission note to squander time in pursuit of unquantifiable pleasures, though that too, and more a lush ecology of behavioural idiosyncrasy as resistant virus, not to be stamped out by standardization, work ethic or will.

I no longer recall how long I sat watching Tornado, 2000-2010, a video documenting his decade-long practice of tracking and diving into small tornadoes just south of Mexico City. And it was not until I watched Rehearsal I (El Ensayo), 1999-2001, in which a bright red VW Beetle drives up a hill only to lose momentum and fall backwards, that I understood the lovely and absurdist humour at the core of the oeuvre. As the car continues to try and fail, the soundtrack follows a band rehearsal where players make strong starts only to lose the thread of the song and peter off into confusion.

Video still from Tornado, 2000-2010, video (colour, sound), 39 minutes. © Francis Alÿs, Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Muscular, empty, tragic, engaged: these are among the impressions that came over me as I moved through this finely staged reliquary of an exhibition, documenting a variety of performance-based acts and making no apology for their afterlife: the ephemera and residue—the notes, the objects, the drawings, the newspaper clippings that at once trail after his body of work and punch through the potentially mummifying effects of the museum context. Here, the by-products of performance, and labour more generally, are intriguing and suspect: excised and posted in a deadpan manner for re-evaluation. Necessary, he seems to ask? “As long as I’m walking, I’m not knowing.”

In Re-enactments, 2000, which follows Alÿs on a 12-minute walk made while carrying a loaded gun in downtown Mexico City, he documents both the original action, which resulted in his arrest 12 minutes later, and a re-enactment made the following day. I stood alongside many watching this video, each of us perhaps returning to study his walk—wild and loose, hand at the ready—and the simple way it evidenced how state violence and organized crime transform the street and sidewalk. Nearby, an array of crime magazines showed a genre of mug shots that appeared to emphasize bravura: young men, dukes up, gazing with pride at the camera and performing karate chops, slashing bottles, monster grabs. A final clipping of President Bill Clinton describing a puppy offered a neat joke—his own hands mirroring the comportment of the “criminals.”

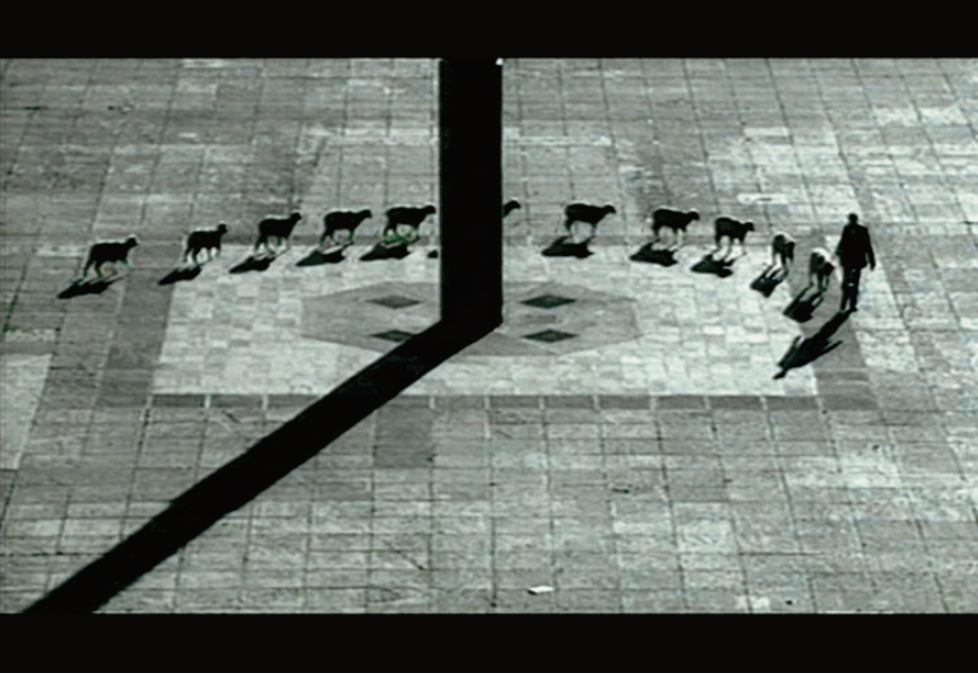

Francis Alÿs, video still from Cuentos Patrióticos, 1997, video (black-and-white, sound), 24 minutes, 40 seconds. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York.

Now and again, I confess I felt a horror in gazing at this work or reading the sober descriptions in the accompanying catalogue. There can be condescension in Alÿs, as in the video Politics of Rehearsal, 2005-2007, where a stripper’s rehearsal becomes a sign of developed/underdeveloped nations relations since “modernity”: “forever arousing, always delaying.” Casting the rehearsal as a second-hand experience seems to emphasize some other authentic experience, when the best of his work suggests just the opposite: we are always rehearsing, and rehearsing is where the magic lies. More, the stripper as signifier is over-determined, or at least over-wrought. It’s another case of putting the girl to work, with an act that, since Barthes, has stood in the male psyche for delimitation via theatrical technique and costuming and a host of other mechanisms that refuse access.

Exiting the buzz of MOMA that July afternoon and heading into the inferno subway for the ride home to Brooklyn, I found my mind pacing over the many contradictions embedded in this work: art can provoke change, art can do nothing; action is its own object, action leads to progress; loser of the game, master of the game, player of the game. I thought of Thoreau and others before who, like Alÿs, walked and wondered and looked out on surroundings that seemed only to value the rich, the heroic, the formed, the beautiful. And I recalled the imperative knowledge, and exquisite pleasure, in all matters useless, inefficient, unspoken and unseen. ❚

“Frances Alÿs: A Story of Deception” was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, from May 8 to August 1, 2011.

MJ Thompson is a writer living in Brooklyn and Montreal. She is an assistant professor in the department of Fine Arts at Concordia University.