Francesco Vezzoli

It may be tempting, upon viewing “Francesco Vezzoli: A True Hollywood Story!,” to dish out a Situationist or Frankfurt School thumping—surely Vezzoli’s commercial content is images that have become capital and egregious manifestations of the culture industry. Watching the feature video, the viewer soon realizes that this artist impishly precludes such critique through fictitious critics who predictably spout, “He is just a fascist artist!” “Francesco’s movies are about Francesco, that’s it!” and “If you are a true artist, you should be beyond exploitation.” Vezzoli thus reduces social criticism to clichéd positioning. Indeed, though Debord and Adorno’s polemics often read as if they were reporting events from today, hundreds of revolutionary moments in the 20th century have arguably synthesized into only a tired, even hackneyed, antithesis of resistance.

Vezzoli is especially adept at destabilizing positions, critical or otherwise. Even in his strategy of appropriation, his authorial voice is spoken by actors and through allusions. Viewing, and certainly writing, about his project invites a deictic madness—it is difficult to parse the fabricated account, containing real and made-up people and events, of an artist making actual fictive works that themselves remake and refer to people and places both authentic and imagined. Even the centrepiece video, Marlene Redux: A True Hollywood Story!, contains little about the titular Dietrich and is instead an invented tabloid biography about Vezzoli. Indeed, the exhibition functions through satire layered with semiosis and différance. To have any idea of what’s going on, it is necessary to know the tabloid TV, Caligula, promoters of contemporary art, pornography, Marlene Dietrich, Bauhaus artists, past Hollywood publicity machines, sexploitation films, Andy Warhol, European auteurs and a host of other allusions.

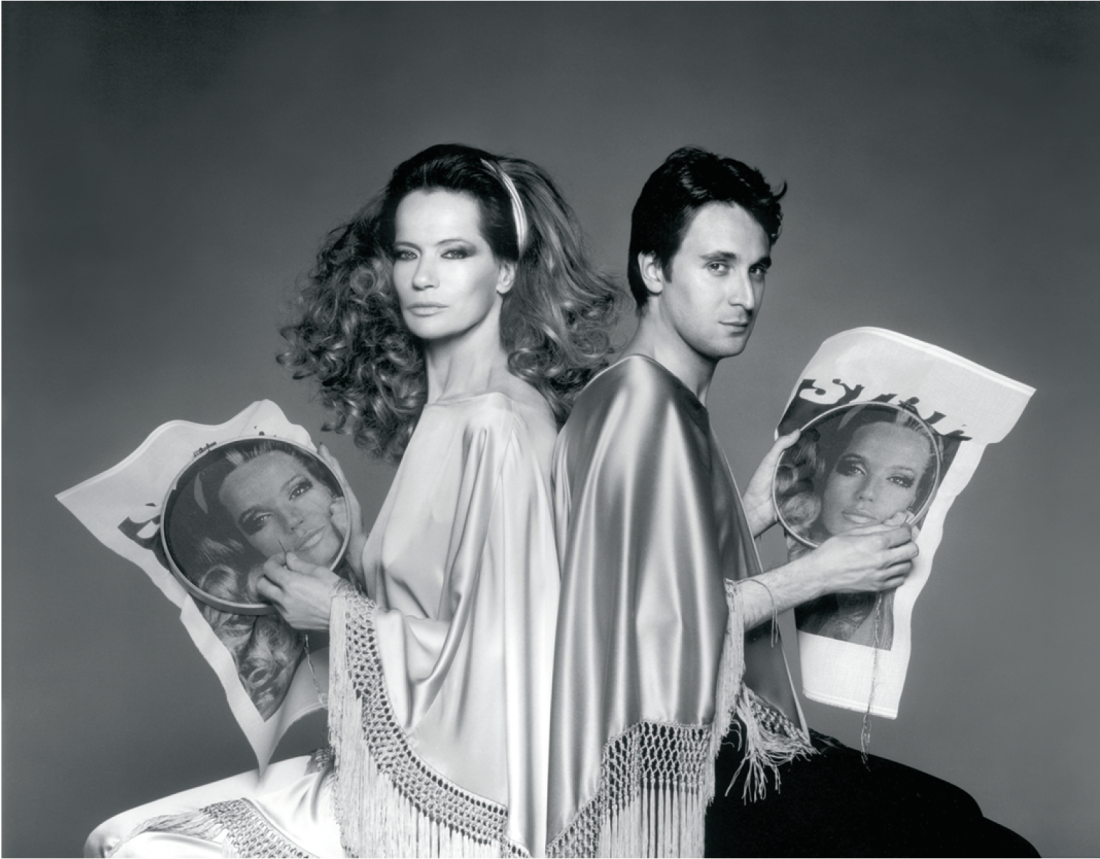

Francesco Vezzoli in collaboration with Vera Lehndorff and Gian Paolo Barbieri, Self-Portrait with Vera Lehndroff as Veruschka, 2001, digital print on aluminium, 100 x 125 cm. Images courtesy The Power Plant.

Vezzoli’s work seems often to take a nostalgic position. His Trailer for a Remake of Gore Vidal’s “Caligula,” 2004 (referred to in this exhibition), speaks to a time when such a movie—the original was released in 1979—was provocative, especially as high-production period porn starring renowned actors. Much has been made of the original film’s explicit versions—with inclusions of torture and homosexual content; this Caligula transgressed boundaries of so-called “straight” pornography. But in a day when once “transgressive” imagery has become quotidian through porn spam and pervasive sites, Vezzoli can only refer to the past possibility of provocation.

In some ways, boundary-pushing films like Caligula may be regarded as milestones of social progress (some might say decline) in which overt sexuality and sexual acts become accepted forms of repression-trumping human articulations. The daring/ explicit/transgressive expressions of sexuality and sexual identity seem parallel to a progressive reading of Modernism. Obviously, filmmakers such as Bertolucci, Polanski, Fellini and Morrissey are often regarded as a part of a late cinematic avant-garde. Herein lies the connection to Vezzoli’s homage to Josef and Anni Albers. The dozens of embroidered Josef Albers’s Homage to the Square works speak to a time—again with a hint of nostalgia— when abstraction in painting was daring/explicit/ transgressive in rejecting realism through formal and conceptual emphases.

However, Vezzoli’s homage to the Homages is a contraventional rewriting of these modernist milestones. By stitching them in bright hues and lamé metallics, he queers these canonical works by rendering them not only as haptic craft but as sartorial and fashionable. He writes sardonic equations regarding kitsch and queerness throughout his show. In Marlene Redux he weaves a gay clichéd biography in which he is raised by doting women and attracted to divas. He offers, in a particularly poignant moment, fictional testimony by gay prostitutes and porn stars, whom he positions to connote his invented downfall or depraved “descent into darkness [that] destroyed his creativity.” Through this gesture, Vezzoli examines a certain tabloid position—a liminal judgment couched in ostensible acceptance. He fittingly casts a gay prostitute as the person who discovers his swimming pool demise. Similar tales about Gianni Versace, Rock Hudson and other celebrities play out like Wagnerian morality tales in which the unvirtuous must pay.

Francesco Vezzoli, still from Trailer for a Remake of Gore Vidal’s “Caligula,” 2005, 5:00 minutes, colour.

In both Marlene Redux and his installation of oversized movie posters, Anni v. Marlene (Double Feature), 2006, Vezzoli recasts the intellectual, socialist, feminist icon, Anni Albers, as a star appearing opposite Marlene Deitrich. These posters are humorous, impossible artefacts from the fictional film project gone bad, as outlined in the video exposé. Here he seems to point to the avant-garde’s uneasy commodification; the ideals of the “Bauhauslers” now seem neutralized by their star-quality recognizability, fetishized furnishings and elevated auction prices. With tongue-in-cheek fantasy, he treats Anni Albers as a contemporary art celebrity even as the posters’ graphics evoke an indeterminate cinematic golden age.

Vezzoli is invariably compared to Andy Warhol. Certainly these artists have in common the (re)presentation of Hollywood and fashion icons, openly gay identities, and abiding fascinations with celebrity, fandom and common denominators. Though better remembered for his paintings and prints, Warhol’s lesser known accomplishments (and those seemingly referred to in this exhibition) include the production of sexploitation films such as Trash, 1970, or Heat, 1972, Interview magazine (by design a tabloid-sized publication), and entertainment television “magazine” shows such as Andy Warhol’s TV, 1981–83, and Andy Warhol’s Fifteen Minutes, 1986–87. In many ways these works were the prototypes for the Access Hollywood and E! programs parodied by Vezzoli. Indeed, he creates many Warholian moments. The hilarious description in Marlene Redux of Vezzoli paying male prostitutes to strip, only to ignore them while masturbating to The Golden Girls television show, seems ripped right from the perfect absurdity of The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, 1975. Vezzoli seems to rewrite Warhol—certainly this Italian artist’s physical works are secondary to the conceptual construction of his persona.

All this is to say that Vezzoli, like Warhol before him, seems to vacillate in attitude between fascination and indictment; in this exhibition he offers for delectation and critique the very promotional mechanism that he has masterfully used to propel his own art stardom. His glitzy dialectics leave no sacred cows. Pre-empting modern ideals while proffering vacuous celebrity trappings, he holds up a mirror that asks why, in art, we might have any faith left. ■

“Francesco Vezzoli: A True Hollywood Story!” was exhibited at The Power Plant in Toronto from September 8 to November 4, 2007.

William Ganis is a professor of art history at Wells College, New York.