Francesca Woodman

If a dark current seems to flow beneath the surface of the Francesca Woodman retrospective at the Guggenheim, it is because we tend to think of retrospectives as belonging to late-career artists and spanning decades of production. Woodman’s prolific photography career was short, ending abruptly with her suicide, in 1981, at the age of only 22. While it is unavoidable to walk through this exhibition unmindful of her youth and early death, focusing only on her biography is to do her accomplishments an injustice, as scholars, Woodman’s colleagues and her parents insist.

Woodman’s photographs confront us with the body immediately. Shot with medium-format cameras, the majority are nude self-portraits in which the artist is set against the interiors of abandoned, half-ruined buildings, in rooms crumbling around the edges. She is squeezed into cupboards, half-erased in a blur of motion, wrapped in plastic and often cut off by the frame. She has arranged her body in imaginative, macabre positions.

Woodman’s ghostly self- portraits lend themselves to a narrative of self-erasure. In variation, she performs acts of hiding or disappearance. Yet the fleeting imprints left behind on light- sensitive paper testify to her unquestionable presence. To borrow from Baudrillard: disappearance is a vital dimension of existence, and Woodman’s pictures affirm this dual reality.

These photographs arise from the particular historical moment of the 1970s, when, as artist Vito Acconci jokes, the goal was to “find yourself.” Many conceptual and performance artists turned to their own bodies. Chris Burden found himself nailed to the hood of a car, Adrian Piper found herself on a bus with a cloth in her mouth, and Ana Mendieta found herself by giving herself a beard. Woodman found herself in these photographs, appearing in one early self-portrait with clothespins fastened to her nipples and torso. Performance was central to Woodman’s practice. Her spare studio can be read as a stage, the props few and poignant.

Untitled, 1975–78, taken while Woodman was a student at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), shows a museum display case full of taxidermy creatures. Dividing the frame into four, the glass of the display case parallels that of the picture plane, except for the bottom right compartment, which is ajar. From here, the hair of a young woman spills onto the floor. Curled inside the case like the other feral animals is Woodman herself.

Woodman’s method of arranging the female body situates her work in close relation with early surrealist photography, which often mined the theme of the caged human-as-beast. In Claude Cahun’s Self-Portrait of 1932, Cahun, dressed as a schoolgirl, is lying inside a chest of drawers, with one arm hanging limply down from her narrow compartment. Man Ray’s Minotaur of 1934 shows the torso of a woman, her head shrouded in darkness, with her arms, breasts and ribcage coming to resemble the horns, eyes, and mouth of a mythological monster.

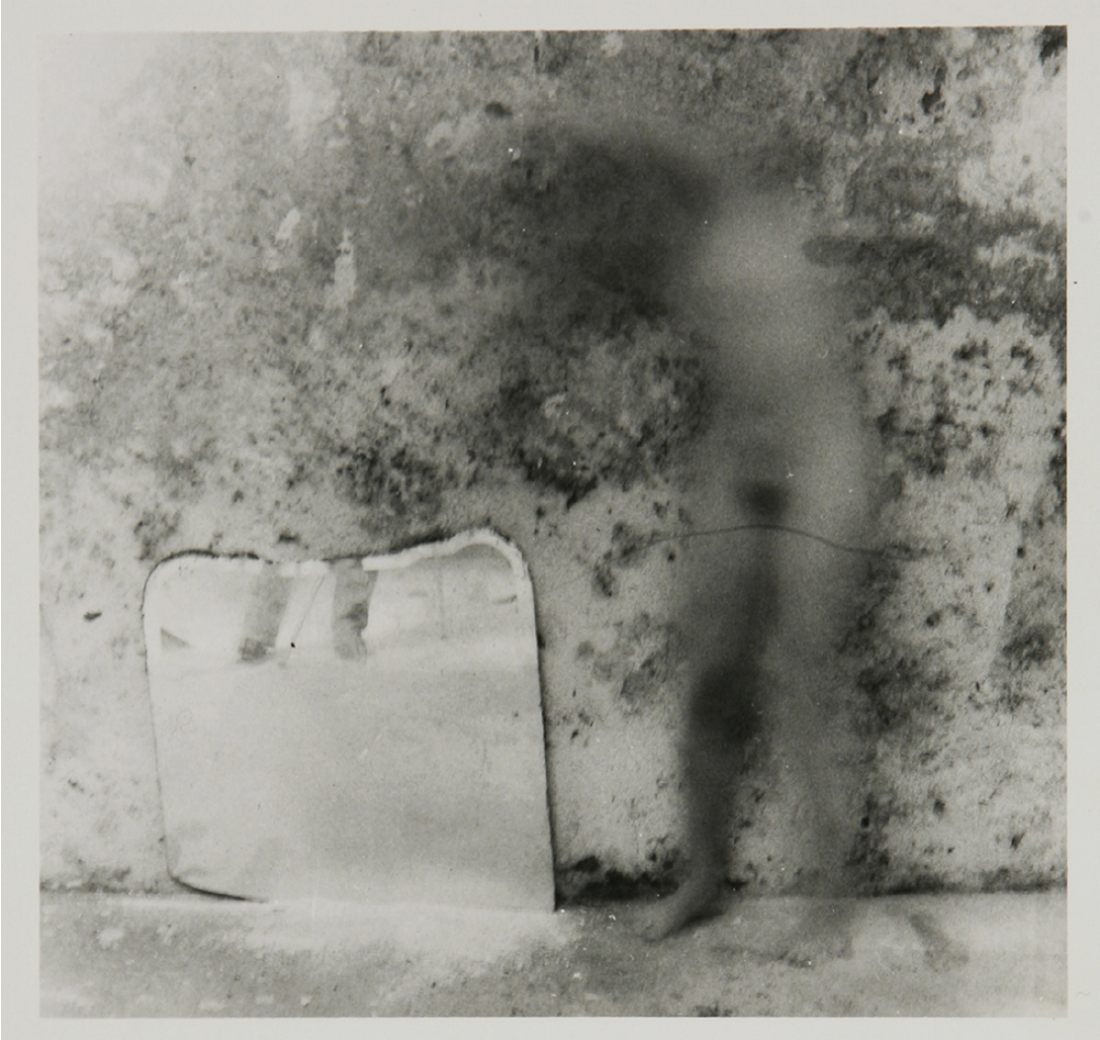

Francesca Woodman, Self-Deceit #7, Rome, Italy, 1978, silver gelatin Estate print, edition of 40, 10.8 x 11.3 cm.

According to Rosalind Krauss, the surrealist photographic techniques of foreshortening, cropping, unusual angling, fragmentation and inversion of the body resulted in forms that are formless or unrecognizable, creating a slippage within the logic of categories. The oppositions between human and animal, male and female, inside and outside, photography and painting, dissolve in many surrealist photographs, pointing to the constructed nature of gender and identity.

This visual and categorical blurring occurs in many of Woodman’s photographs. In Self-Deceit #7, 1978, we see her nude body dissolving into the textured wall behind it, the result of movement in front of the camera and a long exposure. While her legs and lower torso can be distinguished, her chest, head, and arms are entirely formless. Far from something certain, Woodman offers us a female body that is slipping, unstable and caught in a static becoming.

As a whole, Woodman’s work oscillates between showing a conventionally beautiful female body and one that is not only unattractive, but unrecognizable. In this sense, the images can be interpreted as both colluding with the male gaze and subverting it. Consequently, the feminist literature on Woodman reflects this duality and readings often contradict one another.

According to art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson, the recurring questions posed in the abundant literature on Woodman are, “Why Woodman? Why now? Why in this manner?” Virtually unknown during her lifetime, Woodman first came to the public’s attention in 1986. She has been included in high-profile feminist shows, has exhibited internationally and has been widely written about. So the real question might be: Why again?

At the most basic level, Woodman’s photographs are the expression of a woman doing what she wants with her body. Perhaps the continued relevance of Woodman’s pictures reflects the perennial nature of society’s attacks on women’s rights. “The Republican assault on contraception and abortion rights seems to have revived an old question: is sexual freedom good for women?” reads a recent article in The New Yorker (April 16, 2012). The answer to this old question is an old answer, one that we find in Woodman’s photographs: I do what I want.

Like her own body, Woodman’s oeuvre successfully eludes any restrictive interpretation. Beneath the surprising yet undeniable maturity of her work is the experimentation of a young, fearless artist. The power of her photographs, and their freedom, lies in this attitude of experimentation. In images, Woodman apprehends the true complexity of life, not only as something that is given, but as something we must choose, create and continually perform. ❚

“Francesca Woodman” exhibited at the Guggenhiem, New York, from March 16 to June 13, 2012.

Anna Kovler is a writer and artist living in Guelph, Ontario.