Figures and Faces

The Phrenological Time Machines of Steven Shearer

In the interview that follows Steven Shearer told us, “What I like about painting is that it potentially transcends the subject matter of the reference material.” The question to which he was responding was our querying his large collection of Leif Garrett images, and why Garrett? What this interview shows, as have others, is the “thought-full” nature and the thoroughness of the artist’s engagement with his work and working process. Here in particular is where Garrett fits. Shearer’s answer went on to include his own extensive assembly and archiving of images and their ordering in a meticulous taxonomy. His elaboration includes the way Garrett represented the period of the ’90s and the teen media attention paid to beautiful androgynous boy images, to Garrett’s celebrated long hair and to the apparent “lost” personality of the boy star and the sense he had about him of not being entirely “the author of his journey.”

Shearer’s internalized visual memory is capacious, an archive of its own that has absorbed the history of images as far back as images’ own record. His work is a feast for committed art viewers, with whom he shares his own close looking and store. Edvard Munch, Gustav Klimt, the Pre-Raphaelites, the Symbolists, the northern Renaissance painter Hans Memling and his portraits, Neo Rauch, Kai Althoff, the rich fluorescent cloisonné work of Hundertwasser—all northern European, chilly-clime painters using hot colours.

I see no direct evidence of the American artist Mel Bochner in Shearer’s work, but by implied invitation to use our own visual memory, I am drawing parallels between Bochner’s “Strong Language” works and Steven Shearer’s “Poems.” Both artists are making art pieces. Word play, messages of varying intensity, with good manners and polite chit-chat far from being the point, draw us to perceive visual meaning but also optical pleasure. I think of Bochner’s Complain, 2007, a muted palette of short, irritable phrases, luscious oil applied on black velvet. And I look at Shearer’s “Poem” series, which range in size from approximately four by three feet to the brutalist scale of the dwarfing British and German pavilions in the Giardini in Venice. Mounted large on the exterior of the modest Canadian Pavilion, Shearer’s poem became architectural. But that’s not how the “Poems” began. Lists of song lyrics by heavy metal bands, angry and aggressive and meant to offend, were the original texts, mixed more recently with lyrics of the artist’s own making. For him they were concrete poetry; the technique he used to produce them was intense. Black, charcoal black, black as Manet, black as a Robert Longo drawing, stencilled with charcoal, chosen, Shearer said, because “the charcoal would be this severe yet sensual ground to work with.” Questioned about the apparent contradictions between the content and the formal elegance, Shearer explained the material was the hinge that reconciled the contradiction: “It’s how the material body of the actual artwork resonates with the idea.” Here we can attempt—the will is there—to understand what the artwork is for Shearer. It’s a subtle oscillation, a seeking after, but actually not wanting to settle with, an equilibrium. He says he realized that “the tooth of the paper is the resolution of the image,” and he goes on to add that he also used the “weave of the canvas.” With the tooth of the paper and weave of the canvas I hear poetry creeping in. It was the tooth of the paper that told him how to scale the drawing, so the drawing is not only an image, it’s also a made object with the tooth and the weave providing the ground for a space that could be entered—an object, almost sculptural, hence his interest in the frames of the work, as well. Look at Young Symbolist, 2013, acrylic and oil on canvas. Multiple figures that layer and retreat into a dream space, as though collaged, an assembly and layering, thoughts and time and place indeterminate but anchored, or, more precisely, focused on the dreamy boy in the painting’s foreground, his face more fully modelled than the others. With the paint applied—the weave of the canvas is as significant an element as the pigment—almost fresco-like as if on a partly gessoed surface. If you gauge the weave, and it’s only a guess, the proportions of the boy in the context of the painting could be a mathematical equation that sums up perfectly.

The artist as maker and the thing made is an issue, a distinction that Shearer addresses. “Something that announces itself not as a mimic of a person but as a person made out of paint” is how he describes it. The awareness of making and the thin distance between maker and object (do Pygmalion and Galatea come to mind?), and the intense compulsion to make it right and well as a constructed object but still have it credible as a subject, are evident, for example, in the paintings Sculptor and Satyr, 2016; Chiseller’s Cabinet, 2014; and Newborn, 2014. The artist as maker, the incomplete truncated subject acknowledging its status—Shearer has taken it all on and with the topic comes a tempting challenge, even a risk: artist as alchemist, artist as sorcerer, and look at Sculptor and Satyr. I extrapolate and apply some fantastical making of my own: the sculptor’s ears are just that pointy, his teeth dark, maybe vampiric. He holds or hangs onto a small, animated, clay figure. The sculptor’s collar could read as the wings of the clay figure; the background or walls of the room the pair occupy are dense, lush and mysterious. The popular source Wikipedia explains that the word “golem” occurs once in the Bible in Psalm 138:16 and is taken to mean “my light form” or “raw” material, connoting the unfinished human being before God’s eyes.

Artists are creators, primary makers. The best are always questing. The last word in this conversation is the artist’s. Steven Shearer told us, “What I discovered is that for a lot of people, an artist’s real engagement with their material is an attractive subject.”

This interview took place online with the artist in his Vancouver studio on October 23, 2021.

Steven Shearer, Brokenman, 2021, oil on canvas, 213 x 60.5 centimetres. © Steven Shearer. All images courtesy the artist, Galerie Eva Presenhuber and David Zwirner Gallery.

BORDER CROSSINGS: Do you know how many images you have in your archive?

STEVEN SHEARER: A person who is working for me was going through the folders because of the Polygon Gallery show and there are around 74,000, which includes the digital captures of all the actual clippings. Most of those images and clippings are published in the set of 19 volumes that I have in the studio.

Is it ever a burden to have that much material?

No. I also ignore it all the time. I think that’s the exciting thing about the paintings. They start to generate their own subject matter. I’m not looking for pictures in general the way I did initially. Now it’s directed by whatever starts to happen as the paintings develop. I’d recall a face, whether it’s in my archive, or in a painting, or something that’s not in my archive, and then I’d search for that particular face or idea. The associations that come up while I’m working are what directs the image searching.

In a photograph of the ongoing Archive books, I noticed a number of Post-it Notes on the pages, which made me think that you would go into your own archive to decide where you might go next when working on a painting.

Yes, sometimes I do. We actually ran forensic software through all the digital captures to make a mug shot out of every face in the pictures. Whether it’s a group of people or a single image of a person, it figures out what’s an eye or a mouth and it crops a portrait out of that. I also have books where all my images are formatted like mug shots.

Were you already gathering things when you were in Port Coquitlam?

No, but I would arrange things in my room and on my wall. The first time I actually collected anything was a huge pile of teen magazines in the early ’90s that I came across in a junk store. I was drawn to them for some reason, and they moved with me from place to place. Eventually, they started to inform some of my work, and I’m still drawing from them today. In the Polygon show I have a big installation of these dot-tone images from the early ’70s.

Is that the beginning of Shaun Cassidy and the androgynous beautiful boy images?

Yes. The magazines were all from around 1970 to 1972 and it seemed like a period where they were just trying to fill pages; they weren’t really conscious of content or selling things through the images. So the editor would make a doodle and they’d blow that up on a page; or they’d have a picture of a teen idol drawing a swastika on his hand and they would print that. I liked that it was such an unselfconscious scrapbook style of editing, yet was mass-produced and distributed. I found that unselfconscious way of image distribution surfacing again when I started to look at pictures on the Internet.

Steven Shearer, Moonlight, 2005, ballpoint pen on rag paper, 9.75 x 13.25 inches. © Steven Shearer.

What is it that you find so attractive in these androgynous figures?

Initially, I thought I related to the androgynous figures from an historical angle through the idea of symbolism in painting and stillness within a picture. So you have one figure and within that one figure you have the balance of male and female, and that figure is creating its own setting through this kind of internal projection. I’ve always liked that idea and I could understand how these androgynous teen idols fit into that. But when I was growing up, I didn’t have any access to art or art history, let alone the idea that I could even be an artist. My mother and her brother had both studied art when they were young, but the possibility of being an artist in Vancouver in the early ’60s was not a reality. I saw only glimpses of things, like in my mom’s dressing room she had charcoal life studies on the wall, which I thought were nude women but later I realized were actually long-haired guys. And her brother, who was a creative and interesting person, was transgender and he would paint Mae West over and over again. So thinking back, I can say that my idea of creativity was someone creating figures where gender doesn’t really matter because it’s a picture. It can be anything. Obviously, those associations and memories of things shaped what I thought creativity was and what it meant to paint a picture of someone. Later I realized that sensibility and temperament are a huge part of the equation when it comes to doing something like painting.

Your uncle, Jack Carter, did that amazing portrait of two women that you’ve kept.

Yes. He did that as a student. His circumstances were really tough, even tragic, and he destroyed everything of his before he passed away, but that one painting happened to be in a garage, so I got it. That painting was some kind of talisman. Seeing something really powerful like that made me realize it wasn’t unreasonable to think I could apply my personality and temperament and make something as good, myself. I had one of my uncle’s instructors 30 years later and she said he was one of the most talented students she ever had.

Were you actually in a band called the Puff Rock Shiteaters that played live in Port Coquitlam?

No, that was made up. I made a facsimile of an album that I shrink-wrapped and was going to use as a prop to put in a sculpture. It was something that I wished I could find, that I wished existed, so I made it.

I read that you can do a pretty good riff on a Led Zeppelin tune. Did you play a fair amount when you were young?

I did. I’m sure I got my 10,000 hours of mind/muscle coordination. I like to think that it affected my ability to be coordinated and to paint something. I think there’s something with pattern and rhythmic movements and harmony that relates to painting. I’ve never made a painting in which there wasn’t music playing in the background at some point.

I don’t need a playlist, but you do switch musical styles. The figures you use as models or points of departure seem very particular. Even though he was a long-haired pretty boy, Timothy B. Schmit from the Eagles doesn’t turn up in your pantheon.

Yes, it’s particular. There’s something about those images in the teen magazines. Those photographs weren’t taken by professionals, they were taken by parents or fans, so there was a level of unselfconsciousness. When I searched out magazines printed in the following years, I found the images less interesting as they became more about building an identity or selling products, and as a result they were more conscious about what each photograph could mean. Once those pictures became self-aware, there was little room for me to shift their meaning. I always think of it as giving them a material body. The material body helps give them context and resonance. So with those archive pieces, it was how do I present these images that have been lost and are floating on the Internet? How do I give them a place where they fit amongst all these other pictures and still keep some of their original energy?

That raises the question of memory, and one of memory’s manifestations is nostalgia. You’ve said that you’re interested in how we remember and idealize one another. So is your use of this imagery an idealization of a certain period of your life?

Yes. When it comes to any image derived from contemporary and popular culture, I think the ideal viewer is always someone 40 years into the future, someone who has no idea who any of these people are, just like we don’t know who the people are in a lot of early paintings. That doesn’t mean we’re not interested and that they’re not compelling. In the archive pieces there is definitely an autobiographical connection, but mixed in with that is the painterly approach. I’ve approached the archive and the non-painting things from a painterly perspective. It comes down to composition, colour relationships, formal echoes and framing devices. Then you also have the content of the pictures to play off. So some of my background definitely crosses through it. It wouldn’t be interesting to me if I couldn’t read at least some of my experience into the subject matter, but I also don’t think it would be interesting for a viewer if it was only about me.

You have a piece called Faces Inside of Me (2006), and it occurred to me that your entire practice is an externalization of faces that you hold inside, that there is this integral connection between your own being and what it is you’re making from the world.

Sure. I find it interesting that as a species we read all these genetic markers in others, and everyone is unconsciously reading other people and things. I’ve never been interested in painting anything other than figures and faces.

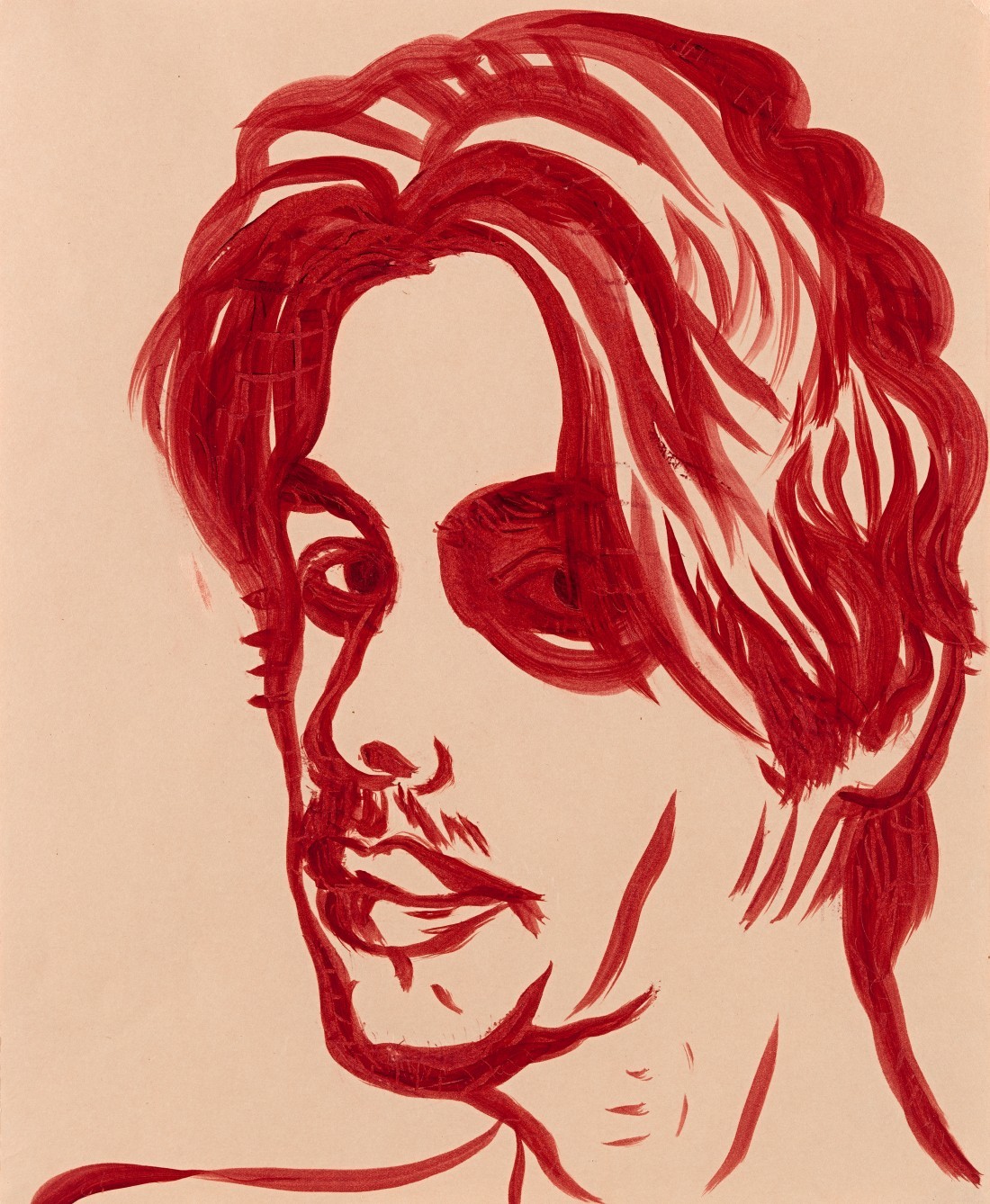

Steven Shearer, Self-Portrait with Black Eye, one of five drawings from the work “Greasepaint,” 2014, oil on Japanese paper, 30.8 x 37.5 centimetres. © Steven Shearer.

But you’ve consciously stayed away from representations of your own image. The only self-portrait that I recognize, and that’s because you named it, is Self-Portrait with Black Eye (2014) from the “Greasepaint Series.”

Well, it’s hard not to draw upon yourself when you’re painting from your imagination. But I don’t want them to end up looking like me. There’s enough of me in those paintings not to feel the need to do self-portraits.

When I look at As a Boy (2006), I read it as an earlier rendition of you.

That’s based on one of the teen magazine images. But obviously the black and white dot-tone image doesn’t look like that. A lot of it was invented. There’s one work, I thought I was a Visionary—But Learned I was a Channeller, that documents renovations going on in my old studio, where a carpenter is pulling out some junk from behind the wall and amongst it is a 1976 Vancouver Sun Entertainment Supplement and on the cover is Leif Garrett. I couldn’t say exactly what the affinity is that I have towards those images of teen idols. I haven’t tried to analyze it. Somehow, they fit into this world that I was building and other things didn’t. I don’t ever struggle over an image, thinking, does this fit? Do I gravitate towards this image? It’s an instinctual kind of thing.

You have three full volumes in your archive of Leif Garrett images, which takes you in the direction of obsession. Is that number because you were a fabulous researcher or was there something particular about Leif Garrett that would make him so central to the archive and to your practice?

What I like about painting is that it potentially transcends the subject matter of the reference material. So I can’t think of him as being an important part of the painting, but he’s definitely an important part of the accumulation of images. I can’t say exactly how everything fits together, but I could relate to it on a phrenological level and I could relate to it having long hair. He also seemed a bit lost in the world and not the author of his journey.

Steven Shearer, The Mauve Fauve, 2007–2015, oil paint and oil pastel on jute, 64 x 53 x 7.5 centimetres. © Steven Shearer.

You worked on The Mauve Fauve from 2007 to 2015. That’s a long work-in-progress.

Well, it didn’t get thrown away. It was just discarded and then reworked.

But when I look at it, at Washy Face (2019), Graceful Ghost (2011) and Blue Woman (2014), the faces on those works seem exquisitely beautiful. Is it possible that all you need from the image is beauty and that psychological and psychosexual connections may not be relevant to your image making? Could you just be rendering beauty?

It doesn’t usually feel that way. I’d have to be more certain about what I was doing. To me, painting is always like flying by the seat of my pants, trying to make something happen. The paintings are the most difficult things to make on an emotional level. What keeps this interesting for me is that it’s always a battle.

…to continue reading the interview with Steven Shearer, order a copy of Issue #158 here, or Subscribe today.