Face Value: The Drawings of Jutai Toonoo

When people talk about the changing face of Inuit art they often reference the work of Jutai Toonoo, the 53-year-old Cape Dorset artist who has staked out new territory in the landscape of contemporary Inuit art. “I’ve always had this fascination with faces,” he said in a 2011 interview, adding that Inuit artists often “do the same things—animals, things from the past, igloos.” Increasingly, though, Cape Dorset artists like Toonoo, Shuvinai Ashoona and Annie Pootoogook are breaking that mould, picturing the social changes that are taking place in Inuit society, documenting the impact of mental illness, substance abuse and violence with harrowing honesty. Toonoo, though, is distinctive in exploring the psychological impact on the individual, making large-scale portraits of himself and others that surge with intensity and complex feelings, charged with the artist’s distinctive, feverish touch. These are particular selfs, not generic figures (the brave hunter, the industrious mother etc.).

Suzie, for example, depicts the weary face of a woman in midlife, her eyes flinching slightly as she meets our gaze. A wild cascade of salt and pepper hair emanates from her head like a kind of force field, signalling a vivid alertness, a counterpoint to her tranquil aura of blue and green. Even though she’s seen it all, hers is still a kind face, ready to hear you out.

In Listening to Music, Toonoo depicts a man with a head phone on—the ubiquitous talisman of mass culture in the North, as it is in the South. Focusing our attention on the earpiece—where he bears down on the details—Toonoo creates a visual image that describes the disembodied experience that these devices afford us. The face is distinct, the articulation of the nose and mouth are precisely described, yet this is also the mask of modernity, in which new media blur and extend our human boundaries, just as Marshall McLuhan predicted. Part of the skull has dissolved away into the picture’s blue ground—the self dissolving into sound and space. The drawing seems to ask: at what cost do we challenge the integrity of our physical/psychological boundaries? It’s an eerie countenance, the eyes dark and unreadable.

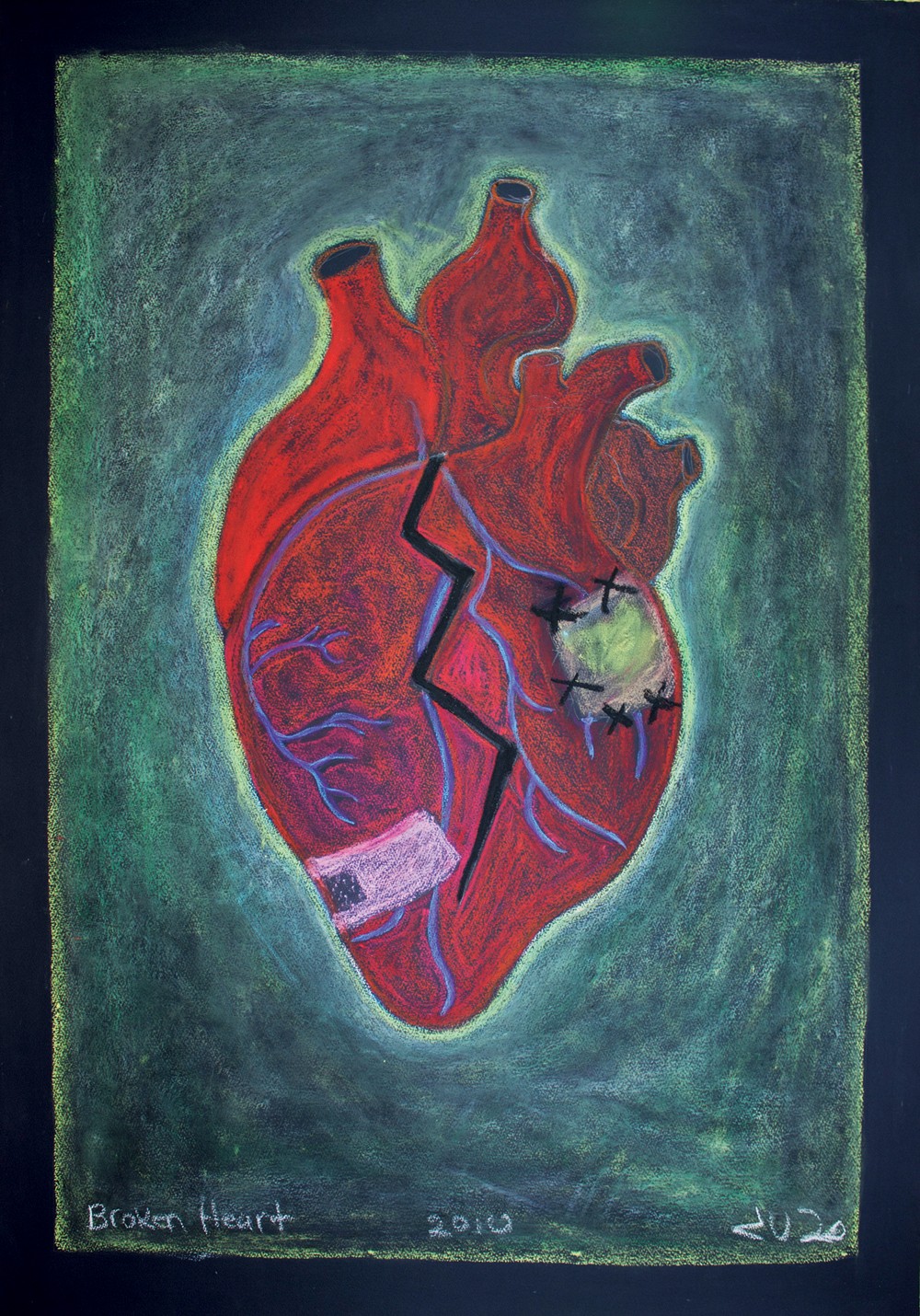

Toonoo has been no stranger to the rigours of life in the North, and Broken Heart shows the scar tissue that comes from a life of missed chances, disappointments and disillusionment. Yet Toonoo here still keeps the beat with a livid red vitality. Leonard Cohen, a kindred poet of broken hearts and soulful self encounter, once said: “There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.” Jutai Toonoo’s drawings seem to agree. We are the sum of the things we live through.

Sarah Milroy is a Toronto-based writer.

Jutai Toonoo, “Broken Heart”, 2010, graphite and oil on paper, 112.5 x 76.5 cm. Courtesy of Marion Scott Gallery/Kardosh Projects, Vancouver.

“Listening to Music”, 2011, oil stick on black wove paper, 112 x 76.7 cm. Courtesy of National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Dorset Fine Arts. Photo copyright NGC, included in “Sakahàn: International Indigenous Art. 17 May 2013 - 02 Sep 2013.

“Sunglasses at Night”, 2011, oil stick, 116.8 x 92.7 cm. Courtesy Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto.

“Suzie”, oil stick, 127 x 106.6 cm. Courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto.

“Life Sucks”, 2009, oil stick, 130.8 x 102.2 cm. Courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto.