Extremes of Behaviour

The Winnipeg Film Group, having suffered a dry spell since the Fall of 1992, is marking its 20th anniversary with a number of new films. Two very different works by two equally different filmmakers premiered in the late summer and early fall, both marked by an ambition and scale not often seen at the Film Group.

The Barbecue, a 48-minute comedy dealing with racism, is the first dramatic work by Winston Washington Moxam. Following on the success of From the Other Side, his documentary on the homeless in Toronto, Moxam is here visibly stretching his filmmaking muscles, seeking a dramatic voice for his personal and social concerns. The results are uneven, with stretches of striking imagination offset by scenes which struggle—and sometimes fail—to find their tone.

The Barbecue is straightforward: Gracie, a young black woman, is taken by her former boyfriend Louis to meet his family. She encounters a variety of prejudices, from completely thoughtless comments to overtly racist behaviour. The film opens with her nightmare. It takes the form of a highly stylized musical number, “We’re All Swedish,” which denies the African origins of the human race and secures the arrogant Eurocentric frame within which she is trapped.

As she wakes up in the car on the way to the barbecue, the tensions between Gracie and Louis become immediately apparent. He has avoided taking her to meet his parents until their relationship has cooled so that he can avoid introducing her as his girlfriend. Things get worse once they arrive: Louis’s flirtatious father, Vincent, let’s slip, “You didn’t tell us your friend was black—a woman.” The other guests keep putting their feet in their mouths. The would-be missionaries Ron and Jan Smith, proud to be taking the Word to Africa, ask Gracie if she can give them some pointers on “continental customs.” They are skeptical that she is actually from Brandon. They discuss her bone structure (“Bantu”) and tell her that she really should take more interest in her ancestry. But the crudest member of the group is sleazy Arnold, who expresses every possible stereotype about black sexuality, pawing Gracie and talking about “dark meat.”

Events climax during a game of charades in which it’s obvious that the participants are familiar enough with each other that they’re able to guess solutions from vague clues. Then Gracie’s turn comes. Everyone struggles to interpret her gestures; until Arnold homes in on Prissy, the silly maid from Gone with the Wind. Gracie tells them that she was playing Scarlet O’Hara and storms away. The various tensions between the others (in particular Susan’s resentment when Vincent flirts with Maggie) erupt into a brief fight which ends when Gracie returns to knee Arnold in the balls.

This final sequence stumbles for a couple of reasons: first, it’s not at all clear to the viewer who Gracie is impersonating, so the participants’ attempts at interpretation are not understood as a mark of blind prejudice. And secondly, the delay in Gracie’s reaction dilutes the impact of her anger towards Arnold.

The denouement, with Gracie sitting unhappily in the backyard as Susan tells her it was her own fault for not speaking up sooner, leaves the odd impression that the problem lies not with those who speak and act through prejudice, but rather with victims who fail to object.

The Barbecue is large and ambitious, a welcome sign from the troubled Winnipeg Film Group, but its interest lies more in watching a young filmmaker looking for his cinematic voice than in what the film actually achieves.

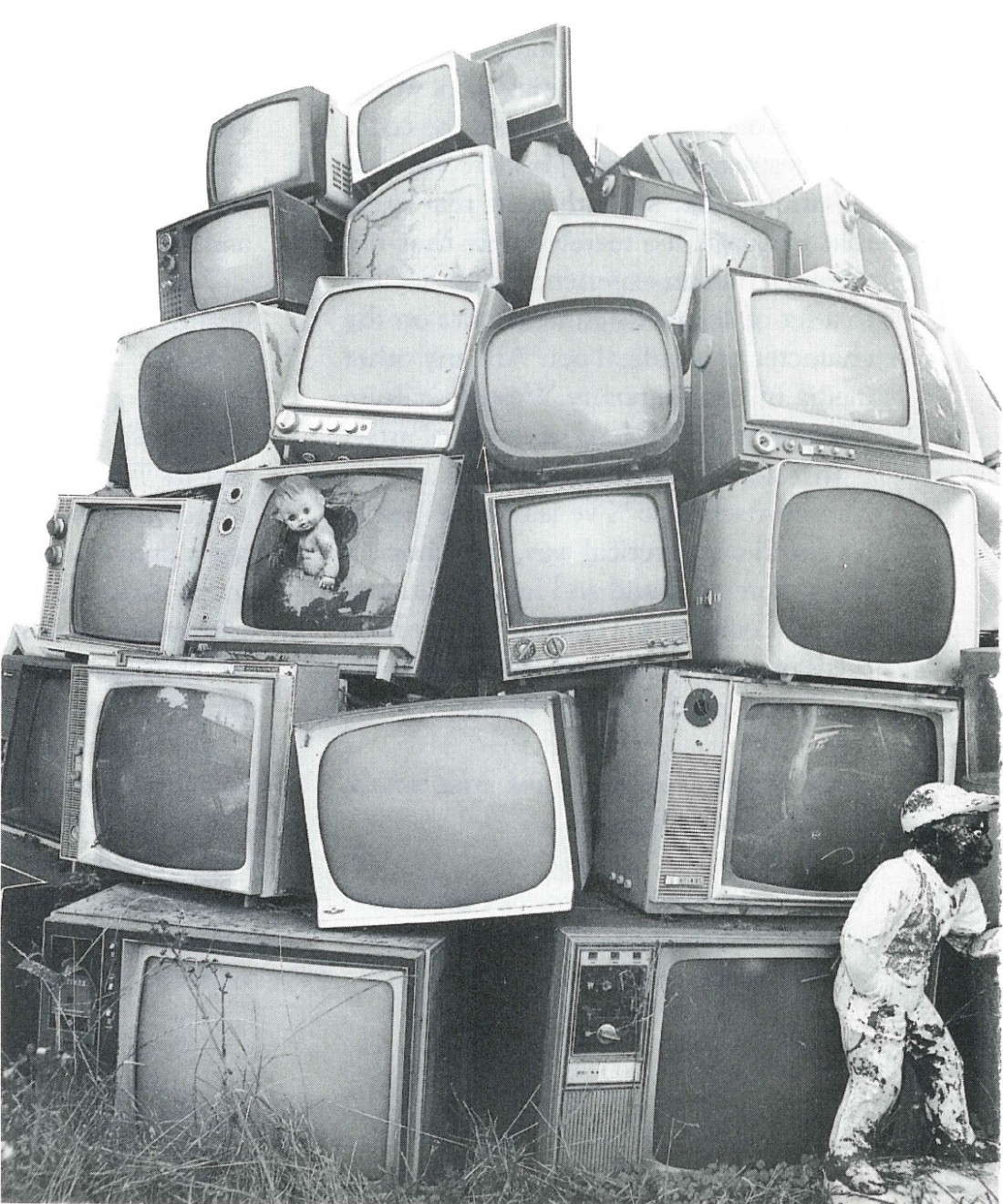

Still from Hunters and Gatherers, Darrell Varga, 1994.

With his third film, Darrell Varga appears to have found his voice in an ironic way: by keeping quiet and letting others speak. In his earlier works, Messages and particularly Quality Time, Varga had a strong tendency to talk at the viewer, presenting a thesis about the nature of popular culture and its shaping effects on personal identity. His new film, Hunters and Gatherers, a documentary about collectors, allows a diverse group of individuals to speak about those effects from their own experience.

In 1993, Varga and a small film crew made a road trip which took them across Canada and around the U.S. in search of collectors. It wasn’t so much what they collected that was important (toys, records, antiques, bread tabs, junk…) as it was the need to collect. The people they encounter define themselves and their lives through the material objects they gather around them. What is really remarkable about the film is just how self-aware and articulate these people are about their obsessions.

There is Cat Yronwode, an editor and publisher of comic books, who collects a wide variety of things: from a particular type of cutlery to fruit crate labels. She collects with the aim of surrounding herself with order and beauty.

Instead of calling himself a collector, John Whitman’s self-description is a man “completely obsessed.” He claims to have been “absolutely normal” until the age of ten when he saw a movie about the Titanic; since that time he has devoted his entire life to the famous ship—at the cost of his marriage and the alienation of his children. He now owns blueprints, and clothing actually worn by survivors who escaped in the ship’s boats. He describes his first encounter with one of those survivors in virtually religious terms.

Mickey McGowan, who develops through the film as the contextual voice for all the other subjects, lives in what he calls The Unknown Museum. It is a house packed from top to bottom with artefacts ranging from household appliances to statuettes of Colonel Sanders. He posits that the material detritus produced by a society functions as that society’s memory, cells in the collective brain which are accessible to everyone who lives in the society. The items in his museum and the juxtapositions between them trigger responses within visitors which “stroke their brain cells”—a kind of “mind aerobics.” He says that all this material constitutes the hieroglyphics of our society and that by gathering it as he does he is making sense of American life.

And that becomes the keynote for all the film’s interview subjects. Through their collections they try to make sense of the chaotic world around them: by temporarily retreating into the relaxed contemplation of 12,000 different sugar packets; by gathering together “bad” images of women in order to trace the course of changing attitudes; or, by accumulating collections of advertising materials, letters or diaries—all of this to make contact with the long-forgotten ordinary voices of the past.

Through skillful editing, Varga establishes an ongoing dialogue among his subjects which deepens as the film progresses. The urge to collect emerges as a driving need to gain individual control in the increasingly rapid pace of modern life and to reconnect with a personal past (collectors often seek out items they possessed or wished to possess in their own childhood). While many admit to being obsessive-compulsive (one declares that collectors are “really sick people, but harmless”), it becomes apparent that what drives them is a larger, more visible version of behaviour shared by most of us—the routines and structures we build around our lives to give them coherent shape and make them manageable.

Back in Vancouver, individuals collect a million bread tabs to give visual form to the waste around them. That waste is usually invisible, a fact at which Barbara Rusch, the founder of The Ephemera Society of Canada, expresses horror; recycling for her, involves a process of erasing the very memory she hopes to preserve. Hunters and Gatherers finds a coherent, shared experience in all of these lives and finds it with kindness and humour. There is no whiff of the condescension or smirking which usually creeps into films of this kind. Varga’s major achievement lies in showing what is most recognizably human in the extremes of behaviour into which we are all capable of slipping. ♦

K. George Godwin is a Winnipeg critic who now lives in England.

The Barbecue written, produced and directed by Winston Washington Moxam, 48 minutes, 1994.

Hunters and Gatherers produced and directed by Darrell Varga, 52 minutes, 1994.