Everyday Every Other Day

The group exhibition “Everyday Every Other Day” at the Blackwood Gallery coheres around a concept that is both disconcerting and potentially transformative. As sociologist and theorist Slavoj Zizek has argued, social reality collapses without a fusion of ideology and fantasy to sustain it. Rather than merely invading our lives, this phantasmal support enables our entry into society through language and binds us as political subjects. Curated by Séamus Kealy, the works in this exhibition are intriguing in their attempts to dislocate the structure of the real. From Marina Roy’s cackling green Martian to Ivan Grubanov’s drawings of Milošević made during his trial, five ambitious projects draw on psychoanalysis and ideology to explore the perversions of authority and the deadlock of desire.

In Marina Roy’s animated video Sleeper, 2004, a scatological Other gleefully violates Adam and Eve reinvented as totalitarian body ideals. Borrowing from Freud’s case studies and Saturday morning cartoons, Roy created a work that functions on multiple levels to expose collective repressions. Fantasies of wholeness and violation are enacted while bodies, cities and eggs explode and reassemble in metonymic chains that owe more to Bataille than Breton.

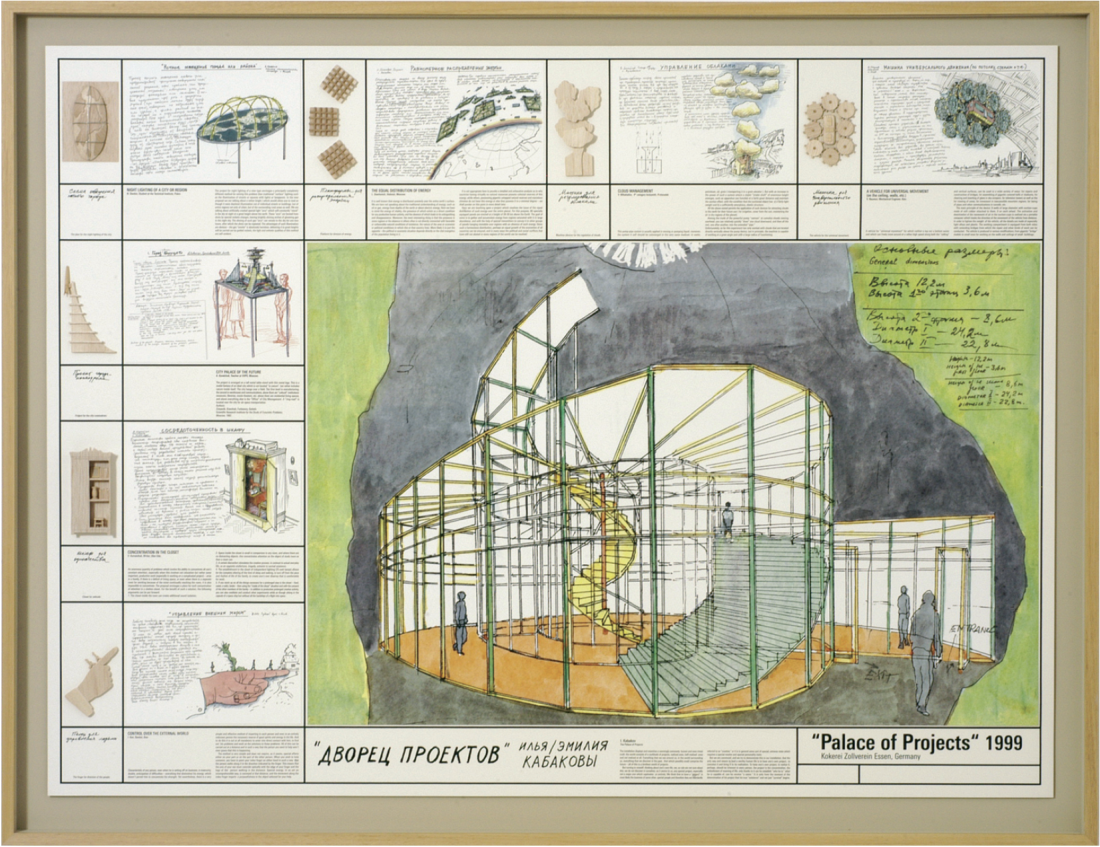

Ilya Kabakov, Palace of Projects, 1999-2003, serigraph, offset lithograph, collé, on Somerset Velvet white paper, 120 x 160 cm. Photographs: Séamus Kealy, courtesy Blackwood Gallery, University of Toronto, Mississauga.

Much like Bellmer’s fragmented dolls of the 1930s, Roy’s assemblages inhabit a body repudiated by fascism and socialism alike. Bataillean Surrealism, as Hal Foster has observed, was less about marvellous chance than a deadly eroticism and compulsive repetition. The Canadian artist’s use of cartoons also aligns her with the domain of the death drive: According to Zizek, characters like Wile E. Coyote occupy a libidinal space where one can live through any catastrophe.

Roy’s other body of work—a series of small paintings entitled “Presidential Suites,” 2005–2006— is equally playful in envisioning a world where power is stalked by its own symbols. In one painting, Richard Nixon is busy with paperwork while an eagle flies overhead and two slabs of meat drain into a bathtub near his desk; in another, a rustic Ronald Reagan chops firewood with a curious fox and bear looking on. As a counterpoint to Sleeper, these pieces address the political more explicitly while still maintaining a grasp on the fantasies that inform it.

Marina Roy, Untitled (Nixon), 2005, oil on panel, 12 x 18”.

Far removed from Roy’s theatrical settings is Ivan Grubanov’s investigation of authority in “Visitor,” a projected series of drawings made between 2004 and 2005. Illicitly produced, these drawings of Milošević and other participants at his trial in The Hague are spare but affecting in their sheer quantity. Snatches of dialogue and observation appear alongside sketches of microphones and faces. Grubanov lulls the viewer through a slowly unfolding sequence that employs the documentary reduction of the courtroom sketch while tackling what is, for many, the iconography of evil itself. Even when Milošević’s face is no more than an outline, it remains eerily recognizable, already an icon.

In approaching the image of evil, Grubanov does so obliquely, careful to acknowledge its dispersion in everyday structures and beliefs. Only then can the viewer grasp the importance of what Kealy calls the “neglected circuits of power” in “international and hegemonic political machinery.” Eschewing resolution in the work, the Serbian artist treats the Milošević icon as inseparable from both the ideological fantasies he inhabited while in power and those that must inevitably arise after his death. With the spectre of dictatorship so close, the viewer might wonder: How can the pieces in this exhibition actually work to restore our faith in utopia, or—more realistically—the possibility of social change?

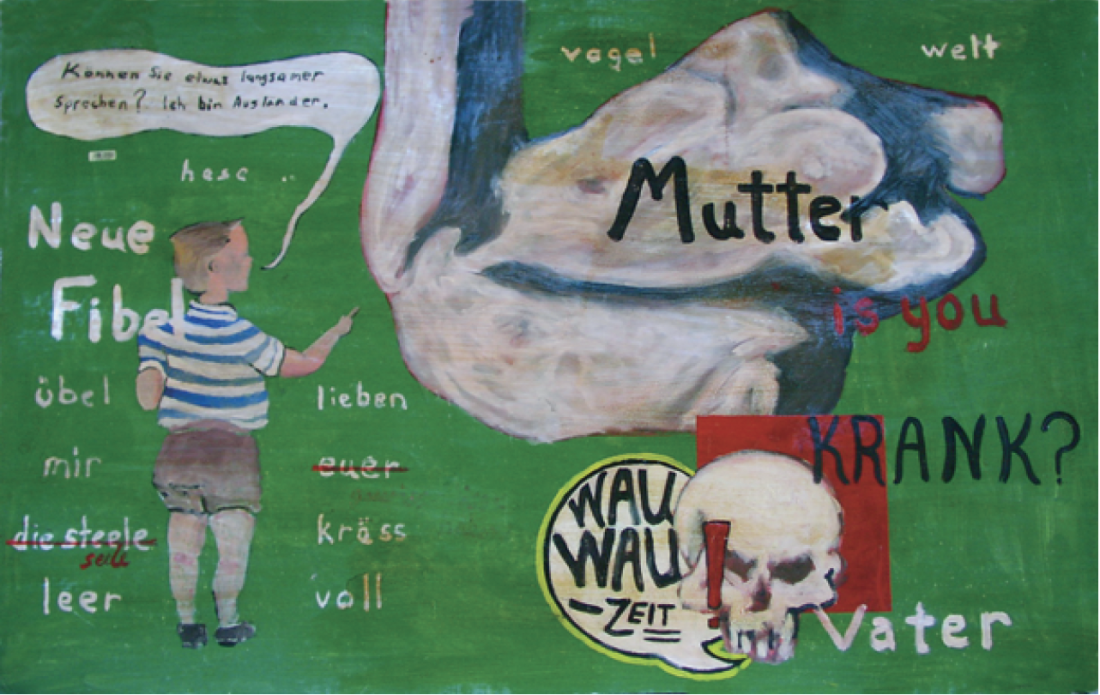

Phil McCrum, Mutter is You Krank?, 2001, oil on paper, 36 x 40”.

“Everyday Every Other Day” opens with prints from Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s “The Palace of Projects,” 1999–2003, a compendium of sketches, plans and homemade maquettes for everything from ambitious social campaigns to humorous everyday rituals. For better concentration, for example, the artists recommend “a prolonged stay in the closet.” For agriculture, they offer plans for “Cloud Management.” Drawing on Modernist utopias, the Russian duo’s projects culminate in a multi-storey construction in Essen that Kealy compares with Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International. If, as Zizek has argued, current notions of totalitarianism may be hindering efforts at social change, these projects provide a lively alternative to the liberal democratic consensus by promoting ideals of collective creativity. These ideals are invoked with a strange combination of irony and earnestness to prove that, as Zizek says, “a worthy human life is to have one’s own project, to conceive it and bring it to its realization.”

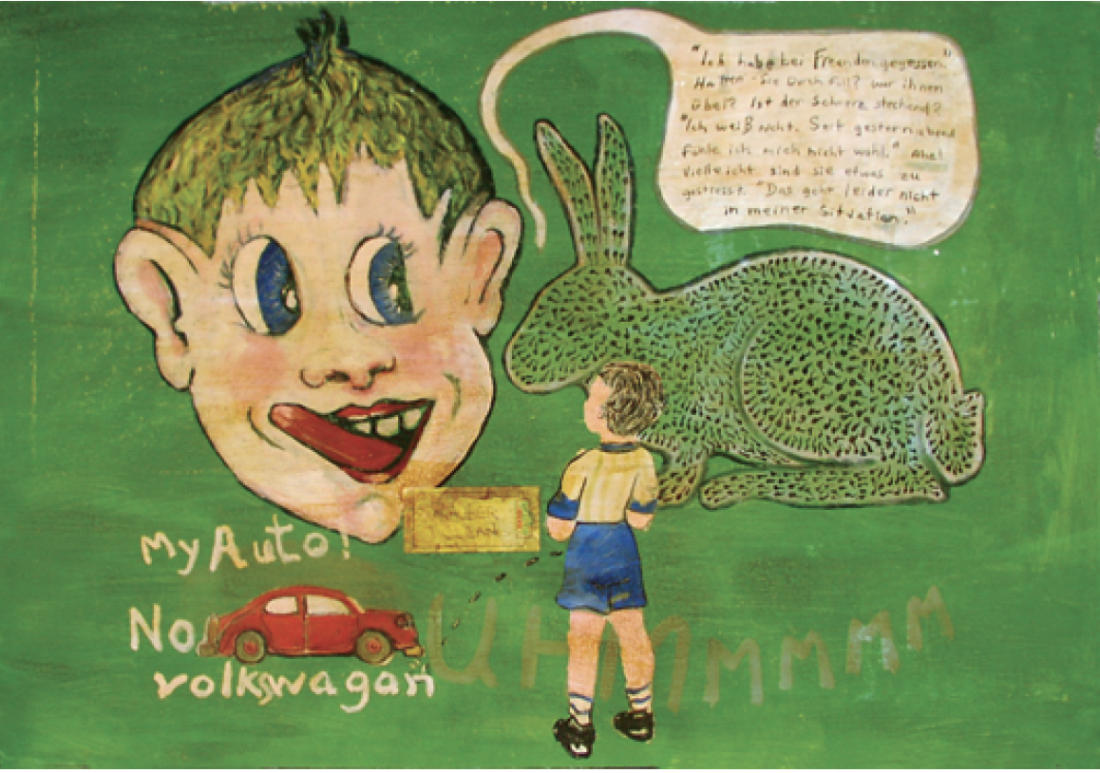

Like Roy’s Sleeper, “The Palace of Projects” playfully engages with ideology and fantasy to underscore art’s utopian dimension. Both borrow childhood motifs—cartoons and craft projects, a child’s propensity for experimentation— and both offer parallels with Phil McCrum’s series of paintings from a Hamburg residency in 2001. Combining crude images with bilingual text on a background of dull, institutional green, McCrum compares his own experience as a foreigner with a child’s turbulent entry into the world through language. In Mutter is You Krank?, a small boy excuses himself for being an “Auslander” before a slab of meat labelled “Mutter” and an ominous skull labelled “Vater.” In My Auto, an enormous child—reduced to pop-like simplicity— reflects on eating his friend, the “sperm bunny.” Arranged around Grubanov’s “Visitor,” these paintings are not composed entirely of childish eruptions and unruly desire; interspersed with the loopy text are demands for the “fair and equal distribution of wealth.”

Phil McCrum, My Auto (or the Red Car), 2001, oil on paper, 36 x 40”.

The last piece in the exhibition— Johanna Billing’s video You Don’t Love me Yet, 2003—necessitates a trek to the Egallery. Like McCrum, Billing addresses the interrelation of authority and language by exploring the failure of conventional notions of love in the context of contemporary Swedish identity. Filmed in a number of locations, bored but fresh-faced youngsters participate in the recording of a repetitive American song from 1984. While McCrum’s paintings point to the subject’s inscription in the symbolic order, Billing’s video reveals the hollow centre around which desire endlessly revolves like a catchy refrain. For Kealy, the music in the video progresses from melodrama to parody and finishes as a “nightmarish” loop. Whether Billing’s piece is nightmarish or hopeful might depend on the viewer’s own sense of the interrelation of state mechanisms, desire and popular culture. In a powerful way, “Everyday Every Other Day” urges us to examine the conditions of ordinary experience. ■

“Everyday Every Other Day” was exhibited at Blackwood Gallery in Mississauga, Ontario, from May 18 to June 23, 2006.

Milena Tomic writes and studies in Vancouver.