Eva Hesse

What it was: to be ten years old, lying facedown in cold earth, when dirt meant nothing and bugs were extra. What it was: to be ten years old, munching on salty pork rinds, good taste and heart failure nowhere in mind. Here, the nostalgia is all mine, writ on the body and conjured by the kid-like fun and beckoning textures of Eva Hesse’s sculpture. From the musty, leather-like folds of Area, 1968—a rolled-out barrel of latex—to the luminous, crispy fat of Repetition 19 III, 1968—circular tubes mushrooming randomly out of the gallery floor, Hesse’s work is a memory palace, a bastion to the senses wrought through child’s play and industrial materials.

But, as in any palace, temptations arise. If sentiment generally undoes great art, here the impulse is magnified by the singular fabulousness of the cultural moment in which Hesse’s art was made: 1960s downtown New York, when rent was cheap, politics were arch and the city was full of interesting people. What’s more, there is the giant personal mythology of Hesse—a beautiful, driven and brilliant figure whose life was shaped as much by World War II and her emigration from Nazi Germany as by personal illness and a brain tumour, from which she died at 34. History of this sort threatens to overtake the work, standing in for rigour or veiling achievement with nostalgia.

Instead, this summer, a pair of excellent exhibitions at the Jewish Museum and the Drawing Centre in New York focused on the performance- based wonder of Hesse’s art, marking the muscle and the making. At the Jewish Museum, curators Elizabeth Sussman and Fred Wasserman showed the balance of Hesse’s breakthrough 1968 exhibition “Chain Polymers,” plus a few important works, made before and after, that document the trajectory of her short, productive career. For instance, Ringaround Arosie, 1965—a relief comprised of two stacked, concentric circles made of wound electrical cord; “a breast and a penis,” she thought afterwards—marked a significant breakthrough for the artist in terms of moving into 3-D space and using found and industrial materials—then uncommon for sculpture.

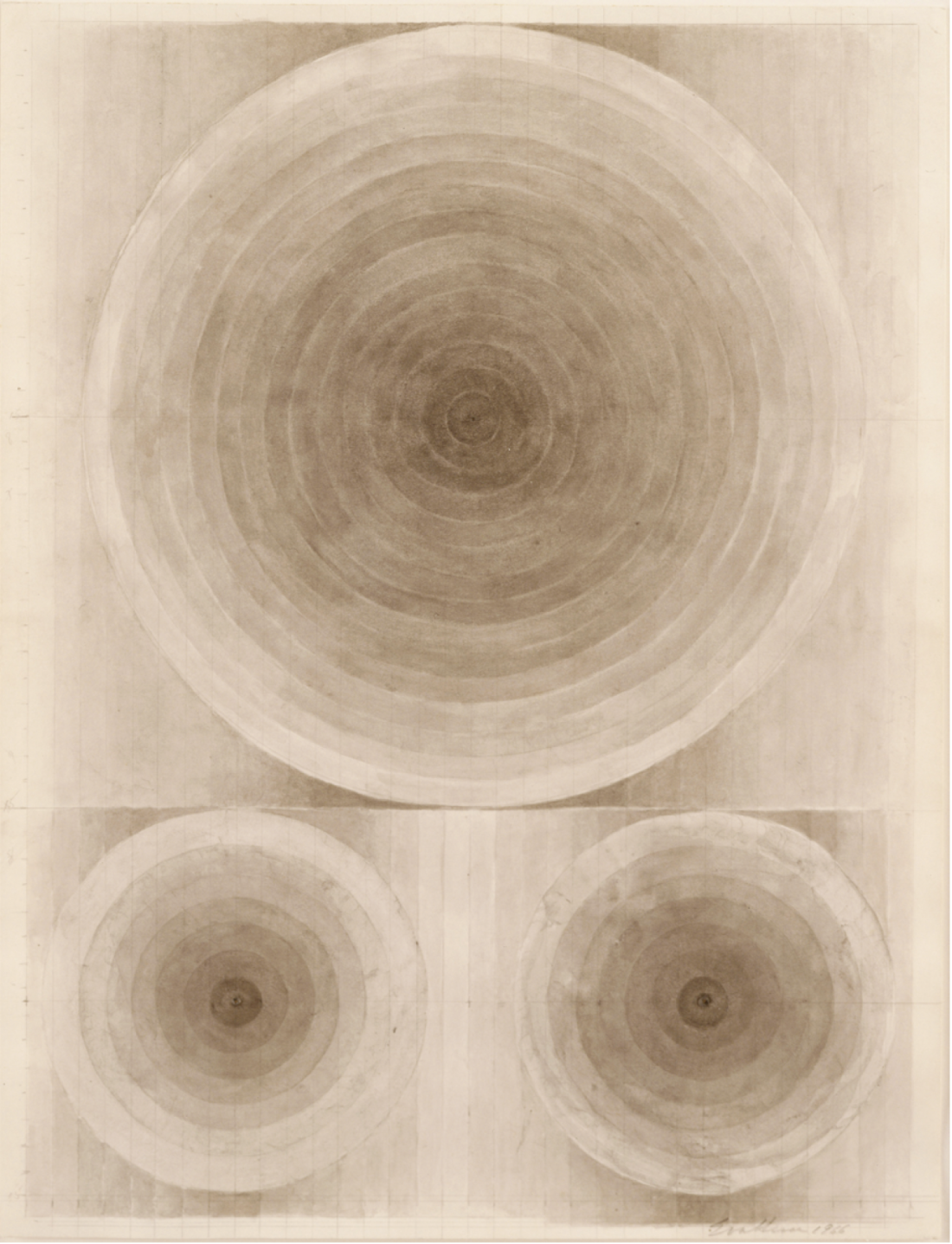

Eva Hesse, no title, 1966, black ink wash and pencil, 11 ¾ x 9”. Collection of Tony and Gail Ganz, Los Angeles. Photographs courtesy The Drawing Centre, New York.

Sans II, 1968, meanwhile, in which all five panels of the original sculpture were reassembled for this show, reiterates Hesse’s unique take on minimalism: an austere series of windows, yes, a relentless stretch of repeated forms. But these are handmade shapes, slightly wonky with the residue of human touch, while the soft, waxy quality of the latex seems to continue to sag like a house in disrepair. Finally, Untitled (Rope Piece), 1970—a work realized when Hesse was near death—suggests some sort of anarchic knitting party. Made of latex, rope, string and wire, the work resists pattern, exploding out of its corner in the gallery. What’s more, its reliance on chance, via the qualities of poured latex, so bent by gravity and time, marked a huge release of artistic control. With its embrace of the accidental and its ongoing deterioration, the work suggests an affinity with early Dada and shifts her work into the arena of performance.

For if minimalists saw in repetition an emphasis on form, Hesse bent the focus to emphasize human action on the object and, inevitably, the failure of replication. If her work conjures kitchens and domestic life, with its cheesecloth and pastry cases and curious bits of hardware-like sculpture, it points equally to the ways we make bearable the endless routine of the mundane world. An unexpected bonus for me lay in seeing Hesse’s humour first-hand, wherein repetition borders on the absurd and the droopy folds and visual belches of unwieldy materials assume a life of their own. Nowhere is this more apparent than in a work like Aught, 1968, in which four pockets of canvas-like latex were stuffed with odds and ends during the building process, taking on baggy shapes and wrinkles as the work settled. Or where the careful arrangement of objects equates the fastidiousness of the gallerist with the aesthetics of the homemaker, as in Schema, 1967, a grid-like board populated by distressed round balls, luscious as a plate of chocolates.

At the end of the exhibition, set neatly apart from the sculpture, in a private room, as if to acknowledge the materials’ threat to reception, stood a biography room. Here again, the drama centres on Hesse’s development, documented through a collection of diaries, notebooks and ephemera, and two wonderful short films of the artist at work. Two things are striking: first, that Hesse studied with Josef Albers, of Bauhaus and Black Mountain College fame. The name offers a tantalizing genealogy, with the notions of chance and play, and other registers of everyday life that are so central to Hesse’s practice, equally vibrant in each school. Second, her grip on temporality as a formal concern—in the deterioration of the materials, in the attention to process—is underscored in meticulous scrapbooks assembled first by her father, then later herself, which track the past elegantly and appear as obsessive feats of collection.

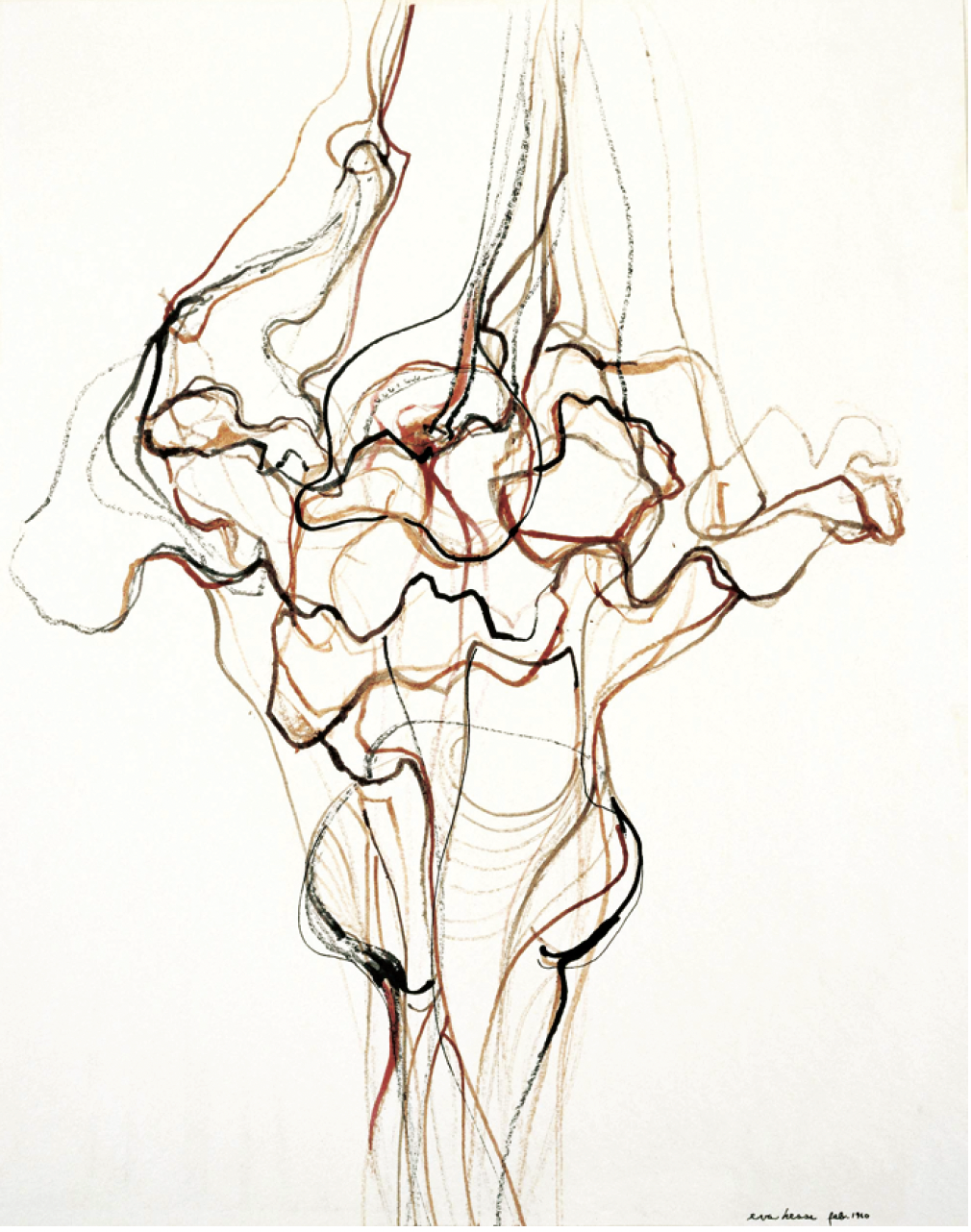

Eva Hesse, no title, 1960, black, brown, and coloured ink, 13 ½ x 11”. Collection of Tony and Gail Ganz, Los Angeles. 40555p001t116.

Downtown, at the Drawing Centre, a second exhibition displayed 150 works demonstrating Hesse’s extraordinary facility at drawing and her relentless inquiry into the nature of her own practice. Curators Sussman, Catherine de Zegher and Sondra Gilman organized works on paper primarily in three groupings: the early, colourful, comic-book-style collages, ink washes and gouaches made between 1960 and 1964, that appear as flattened, miniature display cases crammed with unusual shapes and objects; the drawings made in Germany, between 1964 and 1965, that fuse strange machinery with biomorphic forms; and the latter “grid” and “circle” drawings. Here, the abundance of work is as astounding as the wild energy, the volume of shapes and the clarity of line on view. More than this, notes and drawings made alongside the later sculpture demonstrate the artist’s tenacity with respect to formal concerns. For instance, research into the formal properties and chemical makeup of her materials may ultimately temper our understanding of her use of chance. Elsewhere, personal notes from a journal attest to her ambition and sense of art as a problematic; she draws, in 1965, under the headline “Problems in Art,” a triangle whose corners read “process,” “materiality” and “content.” Underneath, she writes, “don’t pressure yourself about this, it will come when life style opens, it must, it will, one must follow through….”

In the end, Hesse’s compelling narrative and determination to create, against all odds, are overshadowed by the deep strangeness of the work itself: work that transforms the ordinary, ignites the everyday. The result is nothing short of thrilling. ■

“Eva Hesse: Sculpture” was exhibited at the Jewish Museum in New York from May 12 to September 17, 2006. “Eva Hesse: Drawings” was exhibited at the Drawing Centre in New York from May 16 to July 15, 2006.

MJ Thompson is a writer living in Brooklyn and Montreal.