Etienne Zack

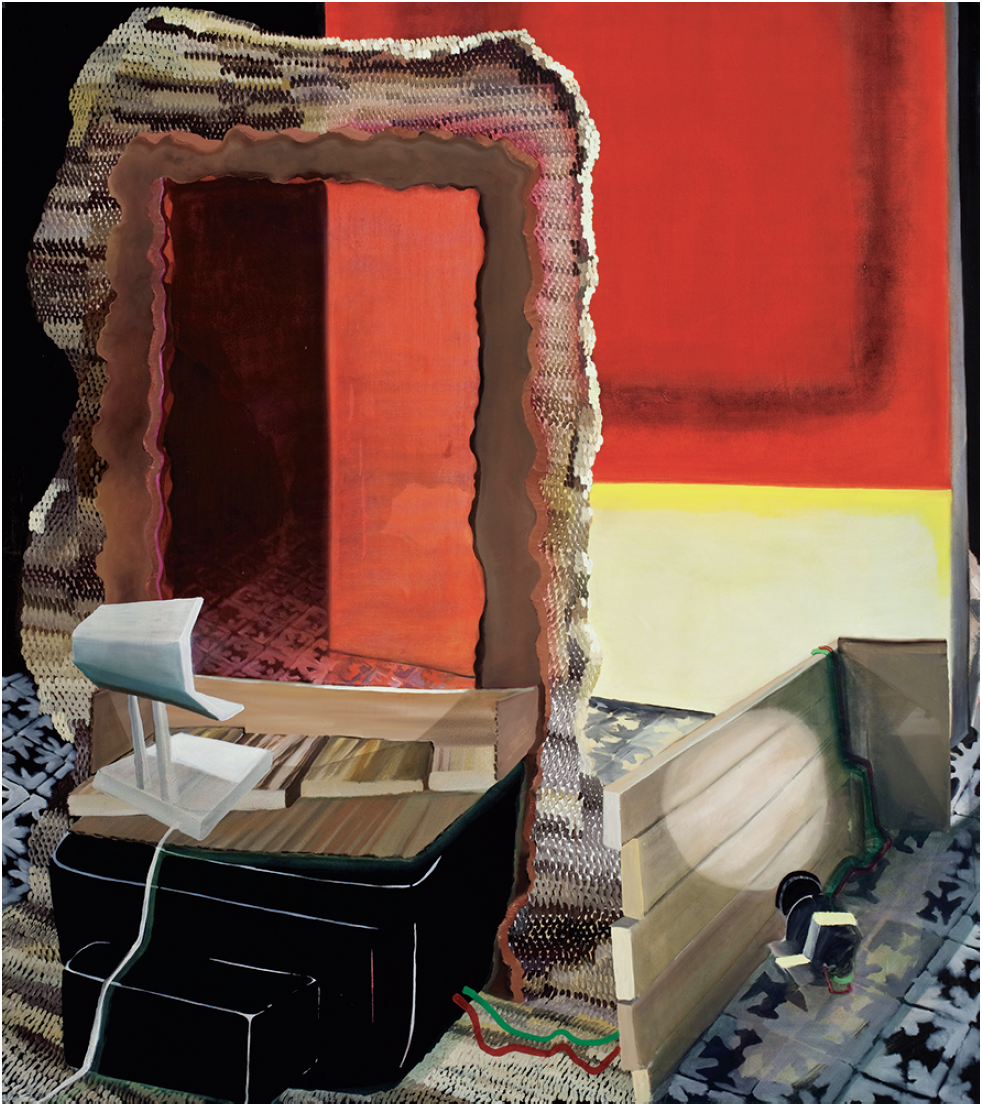

Etienne Zack transformed the exhibition hall of the museum into one capacious incubation chamber for painting, filling it, zigzag-like, with weird geometries that Leon Battista Alberti never dreamt of. Here was all the lovely legerdemain of a painter at his peak. But this was no mere sleight of hand. Zack proved himself a masterful illusionist, and his paintings were like inverted cornucopias, which, after spilling out their hectic contents as though seppuku had been performed upon them, sucked everything right back inside them, blood and guts now including the viewer’s own eye, but with nary a cicatrice in sight. Each of the 20 paintings in the exhibition (all executed over the course of the last six years) paid cannibal-happy homage to the act and the art of painting.

Zack’s restless paintings are rife with fingers that jauntily stick out from, and point back at, the painter’s process and his ethic of making. Self-reflective rather than auto-referential, they offer us the full smorgasbord of the things that painting is and what it might be in a world full of pure appearances. They are arenas of sheer excess and excrescent painterly factuality. But even though their feverish iconographies always revolve around the painter and his tools, they are never experienced as tiresome or repetitive.

Loathe to repeat himself, Zack conjures up dizzying spaces to think and feel in. The painting is the rubric under which related subjects—the studio and its contents, the art gallery where paintings are exhibited, the subjects of a painter, fervour in the making—are all subsumed and subsequently morphed into a powerful epiphany for the viewer.

Etienne Zack, Thorough, 2009, acrylic and oil on canvas, 60 x 66”. Photograph: Guy L’Heureux. Courtesy Equinox Gallery of Vancouver and Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

In two huge new works created specifically for the show, Zack offered a brilliant thesis on what is still possible for painting, reminding us that a postmodernist manual for painters has been long overdue. [Consider that Alberti’s classic treatise Della pittura (On Painting) was penned almost 600 years ago.] Alberti said something like “Let no one doubt that the man who does not perfectly understand what he is attempting to do when painting will never be a good painter.” Well, Zack is a good painter. He knows exactly what he is attempting, what he wants and how to achieve it.

His geometries are hybrid. His own theory of willfully warped spatial perspective is seriously deviant and as fraught with rumours of harmony as it is with discordant revelries. The paintings themselves gestate in Zack’s head over significant periods of time, and the breadth of his purview is humbling in its lack of bracketing. The clutter in the paintings is exhilarating. Someone once said to me (referring to Claude Tousignant’s Chromatic Accelerator), “Il me derange.” I am not sure it was a compliment. It might have been. To say that Zack’s paintings “derange” or spook us is certainly both truth and a compliment. The devastations are profoundly multiple in his hectic compositions, where all the detritus is a sort of deflective camouflage for a pure sensation of painterly vertigo. The inventory inside Zack’s head must be humungous and the process of parts becoming wholes in his paintings highly elastic.

In Spills in a Safe Environment (Abstraction), 2009, Zack proposes an instruction manual for the construction of abstract paintings, and yet it reminds us more than anything else of the recent BP oil spill in the Gulf—and its consequences. There’s also a beautiful painting called Dialog, 2009, that takes Jackson Pollock’s paintbrush for a walk on the wild side with video cassette tapes spewing out shots of Pollock and pornographic imagery in a beautifully calibrated orgy. Indeed, Zack’s is a consummately surrealistic sort of cannibalism. If his paintings are diverting fictions, they are always based on fact, and their truth is part and parcel of their impact.

Etienne Zack, Experience, 2009, acrylic and oil on canvas, 66 x 74”. Photograph: Guy L’Heureux. Courtesy Equinox Gallery of Vancouver and Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

They can be read as inverted cornucopias of images in riotous assembly and sometimes harsh, even guttural, array, but they are calibrated very carefully. They possess constitutive fluidity and a mad Boolean logic that make them work. Commentators have likened his work to the Italian Metaphysical school of painting, but the truth is that he has more in common with a trio like Robert Crumb, Philip Guston and Zoot Simms than with Giorgio de Chirico.

Zack’s show was a considered epiphany of, and a clear victory for, the state for painting now. Everything in this exhibition paid tribute where tribute was due: the artist’s studio where the action is, the museum hall where the trophies are displayed, the materials that make it all possible. But he also subverted various orthodoxies and offered something powerfully new. On this he is not without fellow travellers, of course. Michael Merrill comes to mind. His “paintings about art” are kindred and as self-reflective and as odd. But Zack also heads up a vital and virulent painting cabal that includes the likes of Max Wyse (Montreal), Matthew Brown (Vancouver) and Melanie Authier and Martin Golland (Ottawa).

A long and expansive meditation on what painting might mean in an image-glutted universe, Zack’s visual dementia was at once heady elixir and scold’s bridle. ❚

“Etienne Zack” was exhibited at the Musee d’art contemporain de Montréal from February 4 to April 25, 2010.

James D Campbell is a writer and curator in Montreal who contributes regularly to Border Crossings.