Enn Erisalu

In the early 1990s, Enn Erisalu was forging a distinctive path through the crisis in painting and the politics of representation. Based in Vancouver, widely read and extremely knowledgeable, he was an astute observer of the ebb and flow of art world fashion. He stood at a wry distance, however, from such flux, which at the time included the critical and curatorial ascendancy of photography and the concomitant eclipse of painting, especially neo-Expressionism, which looked like the last, lavish gasp of pigment applied by hand to canvas or board.

Erisalu had never invested his creative energies in emotionally fraught figuration: his inclination was towards the abstract, the analytical and the understated. He used his beautifully executed paintings to reconsider art historical precedents, such as Cubism, Suprematism and the Italian Metaphysical school. Often, his work isolates or juxtaposes geometric or impossibilist forms in ambiguous space as a way of examining the nature of perception as it is constructed by the essential properties of his medium. In some instances, the abstract illusionist forms he created on canvas appear open and obvious; at other times, they seem inwardly focused, almost unyielding.

The way Erisalu applied paint was what used to be called “masterly,” almost academic, yet his formal concerns were critical and deconstructive. His technical facility and soberly composed forms were considered by some to be conservative, but I would argue otherwise. Although it is clad in subtlety and understatement, his work was, and is, a form of provocation. The play between old-school elegance and conceptual rigour in his paintings relates to the dismantling of previously-held notions of what painted representation was, and is, about. At the same time, he clearly loved his medium, relishing all that was characteristic of it.

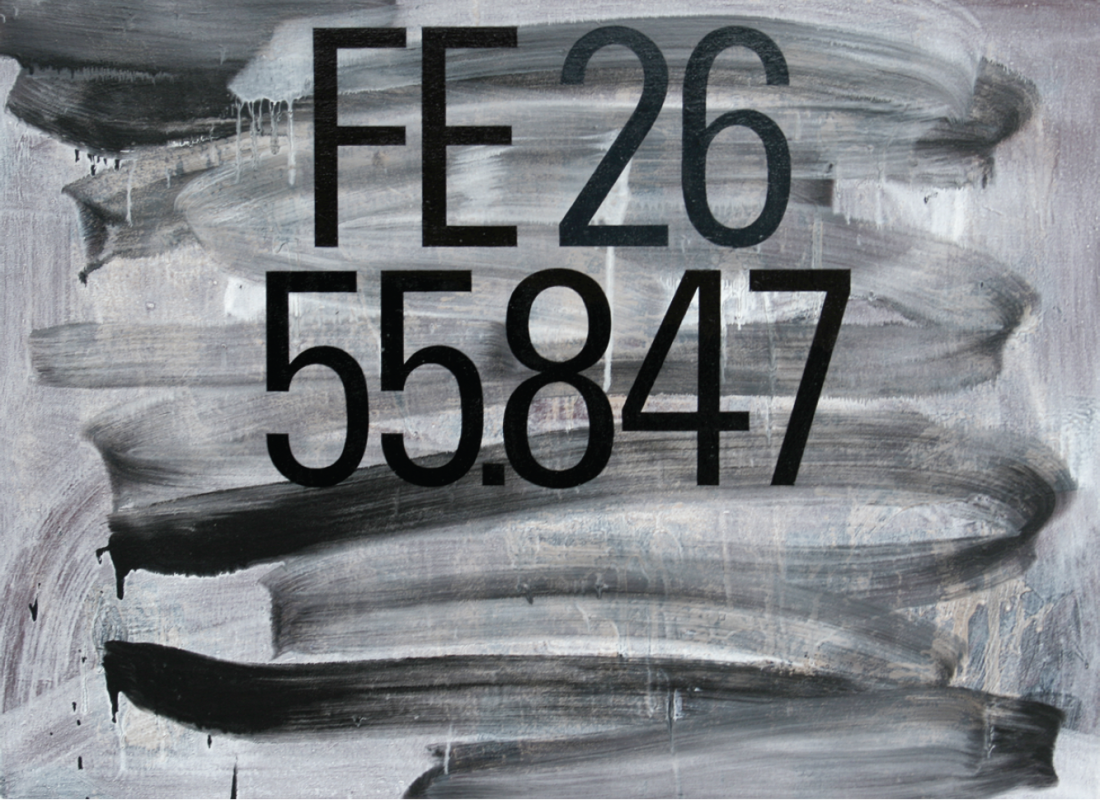

Enn Erisalu, FE26, 1990, emulsion and pigment on canvas, 144 x 183 cm. Courtesy Trench Contemporary Art, Vancouver.

“Paris White: The Language Paintings of Enn Erisalu” revisited a body of work he created between 1990 and 1993, some of which he had previously exhibited at the 49th Parallel Gallery in New York. These are largely text paintings, whose words and numbers allude to their own composition. Executed mostly in adamant black capital letters, they spell out the names of pigments, such as “MARS BLACK” or “PARIS WHITE,” or lay down the atomic numbers and weights of chemical elements, such as FE26 55847, again referencing the matter applied to canvas. Other figures relate to the dimensions of the painting in centimetres, but indirectly: through an equation the viewer is excluded from knowing, they represent the proportions of the work rather than its actual measurements. Still other works in this show flip or invert words that have to do with the acts of making and looking, as in ABSTRACT, which is rendered backwards as TCARTSBA, with the letters spelling ART highlighted in red in the middle of the word.

The paradox in many of these word-game paintings is their play of the cryptic against the obvious. Erisalu wanted to suggest the parallels between visual and verbal cognition but also to create a kind of abstracting interruption, a pause or distance between the subject of the paintings and their implied meanings. The text is executed in an almost mechanical way, but with subtle variations in tone, hue and surface treatment, just barely suggestive of the hand. A variety of formalism is engaged, but it is oxymoronic, related more to conceptualism than to the aesthetic of, say, calligraphic abstraction. The brushwork of the ground on which the letters and figures reside also connects us to a different kind of mark-making from Abstract Expressionism: thin washes of grey or mud-coloured paint have been rapidly swiped, dripped, and blotted on the surface in a manner Erisalu regarded as anti-aesthetic. He saw these swipes, drips and blots as having to do with chance rather than bravura mark-making, and made the analogy between them and the random pattern of flattened chewing gum splotches on the sidewalk outside his studio. Meaning attached to such drips or blots, he believed, was created by the viewer not the artist—an act of inference not implication. Still, again paradoxically, the signs and symbols he deployed, the words, numbers and letters he painted in the early 1990s, are not disconnected from connotation. They signify something. They carry their own very determined weight.

Seven years ago, Erisalu died suddenly and prematurely of a ravaging infection, and it seemed a cruel fate that he had not experienced the wider acclaim he most certainly deserved. His exhibition at Trench Contemporary Art, a young gallery that seems willing to invest itself in the overlooked and under-appreciated, was a welcome reminder of his intellect and his accomplishment. At the time of his death, I wrote that Erisalu’s paintings were imbued with modesty, intelligence, curiosity, solemnity—and delicate touches of humour. It was as if they had absorbed the character of their maker, I insisted.

I still do. ❚

“Paris White: The Language Paintings of Enn Erisalu” was exhibited at Trench Contemporary Art, Vancouver, from February 9 to March 3, 2012.

Robin Laurence is a Vancouver-based writer, curator and Contributing Editor to Border Crossings.