“enendaman | anminigook”

At a recent public talk, curator Niki Little discussed an encounter she once had with a pair of Elders in which she asked about the need for the recentring of women within our culture. The Elders chuckled and kindly told Little that in fact women have always been at the centre. It was with this teaching in mind that Little put together her exhibition “enendaman | anminigook.”

The show is the result of an inaugural Indigenous curatorial residency program at aceartinc. presented in partnership with the Aboriginal Curatorial Collective. Niki Little is a member of the Garden Hill First Nation and “enendaman | anminigook” is her first solo curatorial venture. It is a conceptually intriguing show that marks an important moment within both the local and national dialogues on Indigenous feminism and contemporary art.

“enendaman | anminigook” takes as its starting point the intersection of issues such as matriarchy, traditional teachings, genetic memory and shared authorship, applying them as a curatorial strategy under the guiding principles of the medicine wheel. The medicine wheel seeks balance among the four cardinal directions, in this case linking them to four stages of life.

Wendy Redstar’s work Hot Dance represents the East and the stage of childhood. Hot Dance is a simple blue, child-sized shift dress embellished with gold fringing and suspended from the ceiling at eye level. What may not be apparent to the casual viewer is that Hot Dance is a collaboration between Redstar and her school-aged daughter. The dress itself is reflective of the Crow-style regalia inherited through the generations of women in their community, yet reimagined with new possibility. Hot Dance is a mantle passed on to the next generation, a document of knowledge guided by the women who have come before and crafted by the hands of Crow women of today.

Kenneth Lavallee, Peacock; Ram; Hunter, black boot polish, chipboard, installation view, 2016, Aceart, Winnipeg. Photograph: Karen Asher. All photographs courtesy Aceart, Winnipeg.

To the South is Amy Malbeuf. The South involves youth, a time of change and loss as one transitions from childhood to adulthood. The videos, “The Length of Grief,” explore the passing of Malbeuf’s aunt, a beloved female relation who used to cut her niece’s hair. In the first video Malbeuf and her cousin are side by side, the wind blowing their long dark tresses around them as they remain motionless and without expression. In the second video a friend braids and cuts Malbeuf’s long hair. Their emotion at this grieving ritual is palpable. The final piece in “The Length of Grief” is a small soft sculpture made up of Malbeuf’s two braids, treated with a traditional caribou tufting technique and installed high above the heads of viewers. “The Length of Grief” is a document honouring not only her auntie but also other women, those who join her in the videos and those who carry the knowledge of skill and nurturing.

Kenneth Lavallee takes up in the West as the sole male participant in the show. His three pieces, Peacock, Ram and Hunter, stand as a tribute to his mother, echoing her artistic production in the 1970s when, as a teenager, she painted similar images on the side of her parents’ shed. Lavallee grew up around those images and they left an indelible mark upon him as an artist. His placement in the medicine wheel configuration is across from Redstar, suggesting to viewers a relationship between the two artists’ work. Whereas Redstar collaborates with her daughter, Lavallee looks to his mother for inspiration. The West represents adulthood and Lavallee’s work represents a movement into the footsteps of his mother.

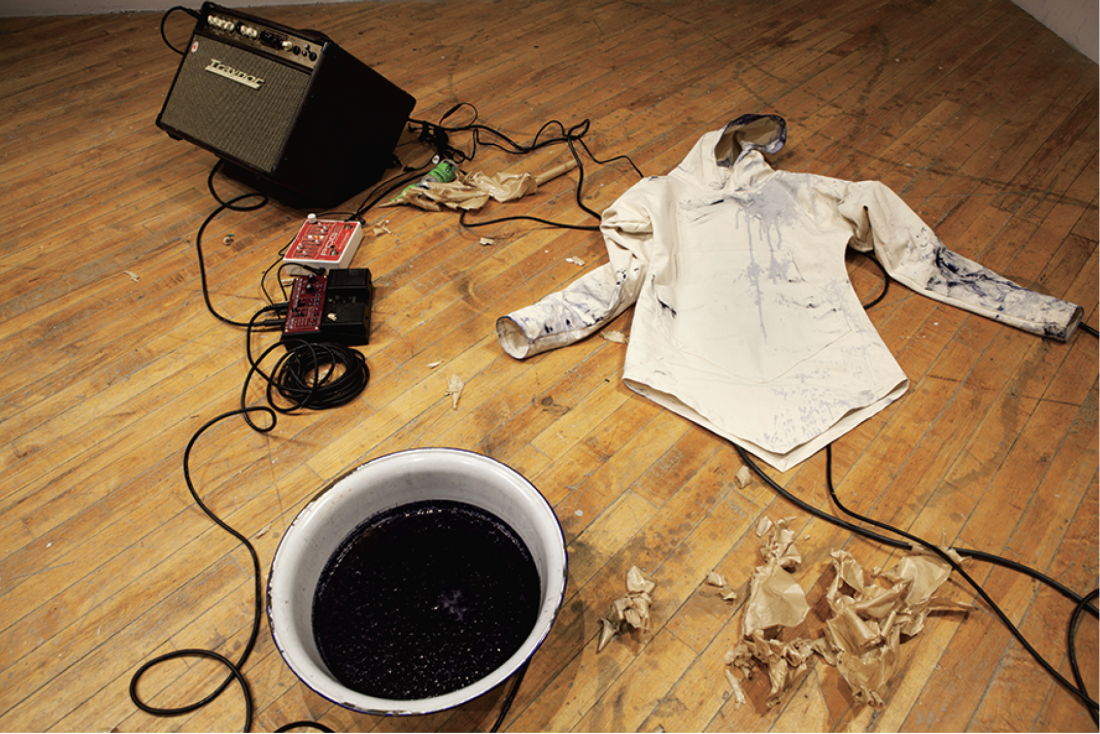

Jeneen Frei Njootli, Melanosite, ephemera from live performance, 2016.

In the North is Jeneen Frei Njootlie, whose piece Melanosite gestures toward elderhood and, by extension, the genetic inheritance of the ancestors in our identities. Presumably taking its title from melanocyte, the name for specialized skin cells which aid in the pigmentation of skin, hair and eyes, Melanosite is a soundscape-creating performance. With a dehumidifier Frei Njootlie pulls water from the air to dye her hair a “Pocahontas blue-black,” staining her jacket and later whipping her hair against the wall in an act of mark making. While her hair colour sets, Frei Njootlie peels plastic from a red square of Plexiglas and presses her face against it, leaving behind facial oils and skin cells. The sound picked up by contact mics attached to the whirring dehumidifier is nothing less than cosmic. The magnitude of that sound is a fitting foil for Frei Njootlie’s investigation of the impact of the minuscule—using the dehumidifier to draw water droplets out of thin air and reflecting on how physical traits inherited at the cellular level interact with perceived stereotypes of Indigenous identity. Once again Little uses the medicine wheel format to point to a relationship from Frei Njootlie in the North to Malbeuf in the South, with their shared usage of hair as a link to personal and community identity.

While traces of Frei Njootlie’s performance remain in the gallery in the form of detritus and marks made, it is uncertain what audiences attending “enendaman | anminigook” would glean from her piece had they not seen her perform on opening night. Redstar’s work, and to a lesser extent Malbeuf and Lavallee’s work, present a similar kind of subtlety which may leave viewers struggling for context. Yet Little appears to be suggesting that to create and take up space, Indigenous feminism needn’t be loud, heavy or aggressive (although there are certainly times when we need to make a noise). Don’t mistake subtlety for silence, she seems to say, women are here at the centre as they have always been. ❚

“enendaman | anminigook” was exhibited at aceartinc., Winnipeg, from January 8 to February 24, 2016.

Jenny Western is a curator, writer and educator who lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba.