Elizabeth Peyton

The criticism surrounding American painter Elizabeth Petyon is sharply divided, with camps of derisive detractors at one extreme and ardent advocates on the other. The critics relegate her to the status of chronicler of the vacuous: her portraits of celebrities, art world figures, musicians and her “cool” friends being no better or no more significant than those found in a tabloid magazine. Peyton’s supporters insist that she harnesses the zeitgeist, that she daringly resuscitated the art of portraiture and painting’s diaristic poignancy at a crucial time in the mid- to late-’90s, and that she uncannily translates the spirit of youth into pigment. “Live Forever,” Peyton’s mid-career retrospective at the New Museum, gives detractors and advocates alike the opportunity to re-examine their assumptions about this artist, with the over 100 works filling two floors of the museum.

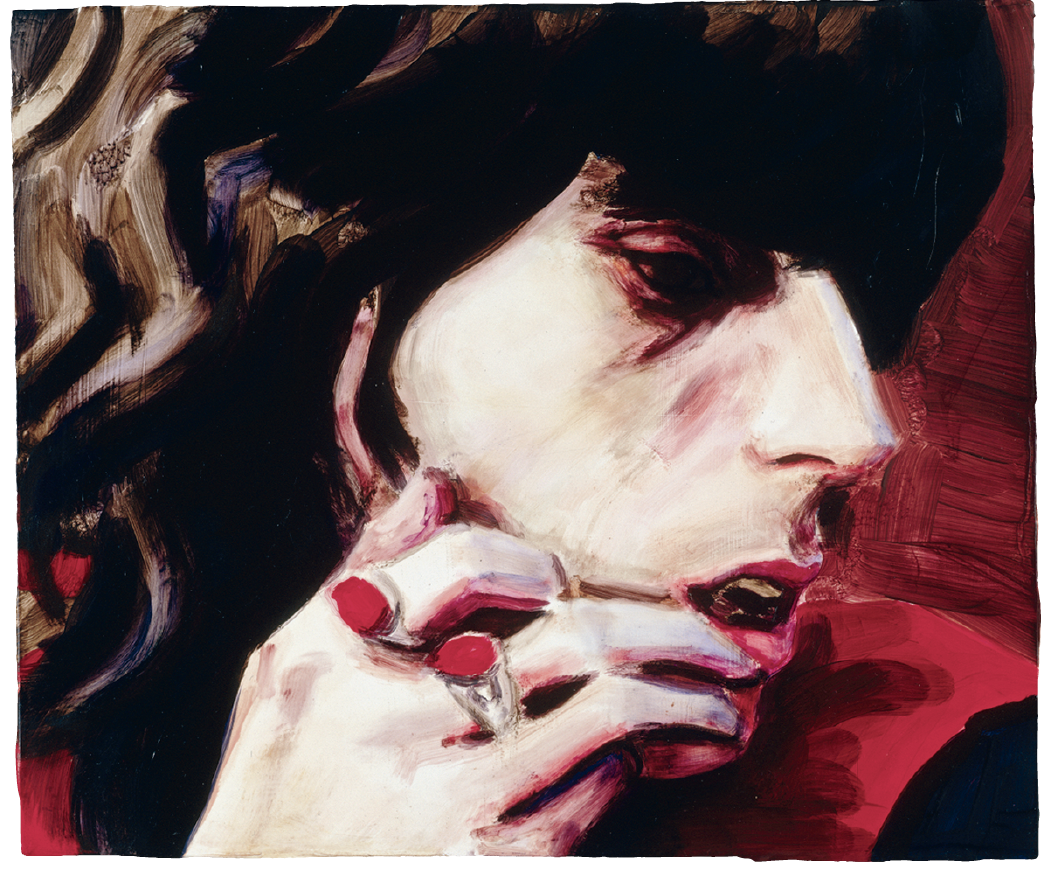

Elizabeth Peyton, Princess Kurt, 1995, oil on linen, 14 x 11 3/4”. Collection Walker Art Center, Mineapolis. Courtesy New Museum, New York.

Small groupings of paintings, hung in loose chronological order, delineate various obsessions— whether Peyton’s, the culture’s at large or, most often, both. Kurt Cobain is the subject of several works in the exhibition’s opening gallery, which is fitting, since this series, in part, launched Peyton’s career after it was shown at Gavin Brown’s enterprise in 1995. Cobain isn’t the only musician to be lionized: ’90s hooligan Liam Gallagher (of the band Oasis) and Jarvis Cocker (of Pulp) are both painted as 20th-century mementoes, and seem as if they had sat solely for Peyton, like patient Vollard once did for Cézanne. But what a blasphemous comparison to make—or is it? Peyton’s cultural rabble-rousers could very well become canonical, eventually equalling in stature portraits painted by Courbet or Van Gogh. This possibility is in part Peyton’s allure. Her portraits highlight the inherent arbitrariness of history’s finicky graces; what of this cultural white noise will be remembered in 10, 20, or even 100 years? In a sense, Peyton’s Pop cultural memorializing raises this much more serious quandary pitting the Warholian truism of 15-minute fame against the possibility of enduring cultural heroes. Here, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Daniel Day-Lewis and Maurizio Cattelan keep pace with Frida Kahlo, Beethoven and Delacroix. The effect of Peyton’s even-handedness in choosing whom she paints veers toward an irreverent, transhistorical free-for-all.

Elizabeth Peyton, Jarvis, 1996, oil on board, 11 x 14”. Hort Family Collection. Courtesy New Museum, New York.

What is inarguable in this 15- year overview is the fact of Peyton’s mastery of her medium. Though there are some paintings on canvas in the exhibition, most are on small boards; and hardened paint extends beyond the surface to create beautiful, uneven edges. (This crude edge can be viewed through an art historical filter—the paint ceases being a means to an end and instead represents illusionism’s end, though this isn’t necessary.) Peyton’s palette is chromatically bright: unexpected instances of yellows, greens, pinks, and blues appear in these paintings. Jarvis on a Bed, 1997, for example, is filled with a luminous lemon yellow; in Nick (La Luncheonette, December 2002), 2003, purple neon light uncannily reflects off the side of Nick’s face.

Elizabeth Peyton, installation view, New Museum, New York, 2008. Photo: Benoit Pailley.

In general, the composition and colour relationships upset the traditional compositional structures expected from portraiture. In some cases, subjects’ faces are completely obscured by brightly coloured objects in the foreground (a bouquet of flowers, a can filled with pencil crayons); in others, the subjects, seen close up and sometimes from odd angles, are cropped, no doubt the ingrained influence of wanton digital photographic framing.

In Art and Illusion, EH Gombrich refers to realistic illusionism as a “willed, hard-fought achievement of our culture.” These works are a welcome reminder of this important tradition, and of the skill and sensibility required to tame paint into universally recognizable form, no matter how non-traditional they can be. Even with their tauntingly hip subjects, Peyton’s portraits situate the viewer within a discernible art-historical trajectory. It’s a useful exercise in self-reflexivity.

Elizabeth Peyton, Keith (From Gimme Shelter), 2004, oil on board, 10 x 12”. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Courtesy New Museum, New York.

Interestingly, it is in the aftereffects that Peyton’s work ceases to feel memorable. Colourful and compositionally unpredictable, historically questioning, and skillfully rendered as they may be, one is left with little to no impression of them at all. They are momentarily worthy and then forgotten. Perhaps satisfaction can be found in the internal logic of this reaction: like her subjects, Peyton may require many more years in order to leave a significant lasting impression. ❚

“Live Forever: Elizabeth Peyton” was exhibited at the New Museum in New York from October 8, 2008, to January 11, 2009.

Julia Dault is a New York-based artist and writer.