Eliza Griffiths

Eliza Griffiths’s exhibition “Actes d’amour” at ELLEPHANT in Montreal presented a strong grouping of new and recent works in the artist’s signature manner. Her work has, for years, been a standout practice in figurative painting and drawing in Canada, of the kind that seamlessly marries a mastery of textbook, old-school technique and the tradecraft of experience with complex, imaginative conceptuality. Her recognizable skill set and key visual interests were persuasively manifested in this show, with a wide and visually thoughtful range of touch, delineation, design and rich colour pictorially interconnecting and gelling together within each piece and across the space of the gallery.

Eliza Griffiths, installation view, “Actes d’amour,” ELLEPHANT, 2016. All photos: Guy L’Heureux. All images courtesy the artist and ELLEPHANT.

On closer inspection, though, this series of paintings and works on paper or vellum were subtly differentiated from most of her previous production in their pensive sombreness of mood, atmosphere and scenic propositions. It was as though the volume had been lowered slightly, while the track that was playing had segued to a more soulful delivery than the song before. The work, compared to past series, showed a deepened concern for raw states of intimacy and vulnerability, of and in between her cast of invented characters. As a director of her fictitious ensemble, Griffiths has often aimed at considered, serious commentary and critique on the fabric of our social and psychological lot, and she’s done so with a certain levity and a vacillating but clear sense of ironic distancing. There has always been the impression that she peoples a world that is a projection of our own in a way that is emotionally wholehearted but intellectually skeptical. This is evident from her “Karate Girls” on, through all her related projects: “Dystopic Romances,” “Optimistic Dysfunction” and “Urban Narratives.” Sexiness is something in particular that comes to mind vis-à-vis her work as a notion that has been applied to painting in various different ways, and a quality that Griffiths has often achieved.

But here, as in the small, sketch-like drawings Nose Rub I and Nose Rub II, while risking a possibly ridiculous overdose of cuteness, she conveys in the scene portrayed, and in her making of it, exactly what the title of the show promises— some species of love act, undeniably captured in its emotional music. It’s the same in the very large canvas I have you/Bon secours (which glows warmly despite being in cool colours), where a female figure holds a slumping male figure from behind. Nothing is spelled out about where these people are or what’s happening to them, but it seems impossible not to get it; the characters themselves have an archetypal symmetry but also a quietly personalized sense of pathos and individuality.

In Chaos and Love in the Morning, a woman is either buttoning or unbuttoning her blouse while smoking a pencil-thin cigarette and appearing, in some kind of aside, to address a small, beautiful bird. The viewer is immediately drawn into the weird content of the drama, possibly cast as the woman’s lover, possibly as a voyeur (or both). The diaphanous quality of the atmosphere and the surface of the paint’s skin itself produce a kind of numinous feeling, so that the love and chaos in question have a sense of elation to them. A glowing yellow lampshade anchors the scene, as well as improbably seeming to anthropomorphically observe it with us. Of special note in Griffiths’s work is her chromatic approach. She is strong enough in the deployment of saturated hues to favour a direct appeal to our reactive emotions (and her own) through the use of colour. She can nuance a colour idea in a manner that feels powerful and sensitive, loud and quiet at once.

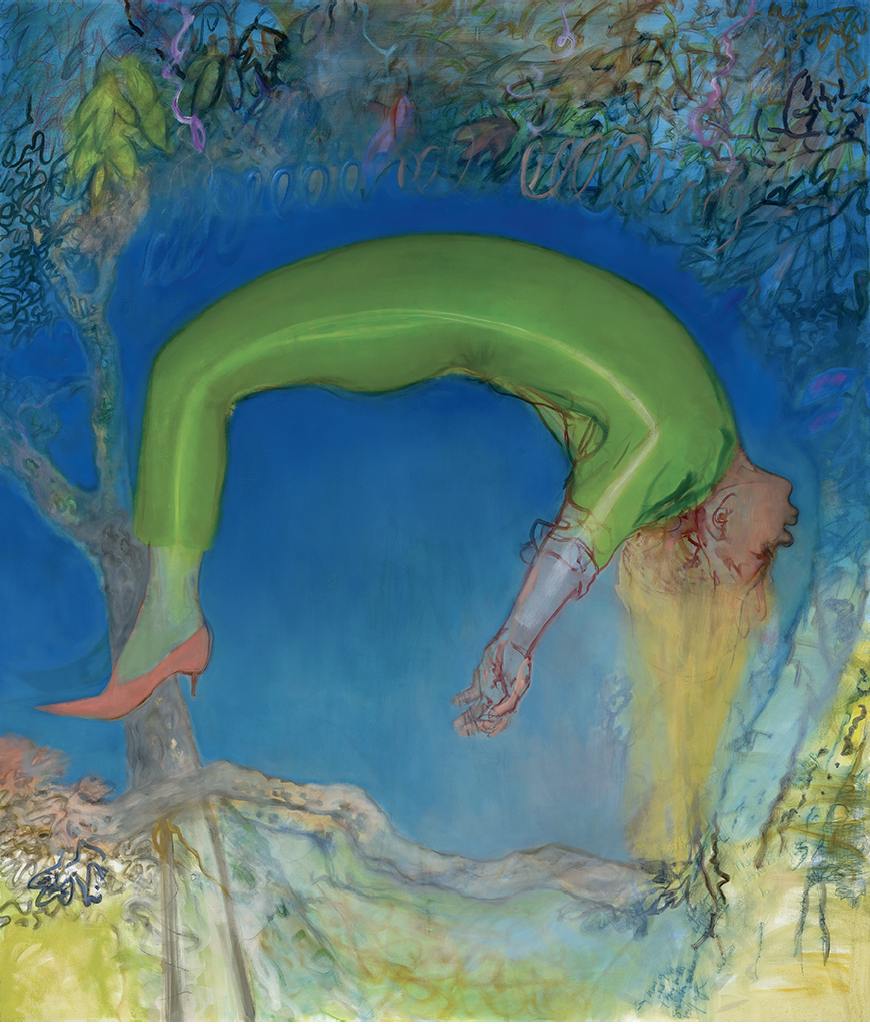

Levitation, 2016, oil on canvas, 172 x 148 cm.

In the mixed-media drawing Party, colour is used in a more garish way than in most of these works, and her style is more blunt and caricatured than is often the case in her drawings. But here these elements add useful pressure to the mix as our eyes start to notice the details of the figures’ arrangement. In this coyly typical setting of a refreshment-fuelled, late-night fête of some kind, the poses and expressions are in every case a fully realized encapsulation of someone’s complexity. Everyone is angry and gratified, happy and depressed to be there. Compressing this very credible social tension into a piece is a tough proposition, one that Griffiths pulls off with finessed ease.

Possibly, though, the killer piece in the show is Levitation, a medium-large, vertical-format painting on canvas whose vibrant luminosity, simultaneous juxtaposition of loose and tight rendering and awkwardly perfect composition come together to kick up the voltage. A female figure in a laser green jumpsuit floats horizontally upward, face up and head back, her long hair, arm and leg dangling down as though the magical force causing her body to defy gravity is centred on her lower back, and the rest of her is floating away only by grace of that. She wears an outlandish but somehow stylish pink high-heeled shoe on her one visible foot, while the landscape around her crackles with heightened energy, as though the entire field of activity here has come to life and is watching the figure floating—and possibly also watching us watch her. It hits hard as a metaphor for loss of control by possibly transcendent experience. Whether this woman is causing her own situation is impossible to say, but she represents the crest of Griffiths’s expressive wave, pulsing up, pulling down, and moving outward. ❚

“Actes d’amour” was exhibited at ELLEPHANT, Montreal, from November 5 to December 17, 2016.

Benjamin Klein is a Montreal-based artist, writer and independent curator.