Edward Burtynsky

Edward Burtynsky has travelled the world in pursuit of the human-altered or industrial landscape. By his own plain account, his photographs seek to demonstrate where the things we consume come from, where they’re used and where they go after we’re done with them. His subjects have ranged from marble quarries in Italy, coal mines in British Columbia and oil fields in Azerbaijan to freeways in Los Angeles, ship-breaking beaches in Bangladesh and entire towns in China filled with toxic e-waste. He has shot the biggest open-pit gold mine in the world (in Western Australia), the biggest open-pit copper mine in the world (in Chile) and the biggest hydroelectric project in the world (the construction of the Three Gorges Dam in China). The large size of Burtynsky’s chromogenic prints has to do with his desire that viewers have a bodily as well as visual engagement with his work. This experience is, of course, commensurate with the vastness of his subject matter.

The Surrey Art Gallery show in early 2009 focused on images Burtynsky took in Alberta and British Columbia between 1985, early in his career when he was coming to some understanding of what his self-assigned undertaking would be, and 2007, when he travelled to the Alberta oil sands as part of his ongoing, world-wide “Landscape of Oil” project. At the same time, the exhibition celebrated Burtynsky’s gift of 37 photographs to the Surrey Art Gallery.

Edward Burtynsky, Mines 17 – Lornex Open Pit Copper Mine, Highland Valley, British Columbia, 1985, chromogenic print on photographic paper, edition 8/10, 27 x 34”. Image copyright Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto, and Paul Kuhn Gallery, Calgary.

As he discussed in a recent public talk at the gallery, Burtynsky understands full well that the combination of formal beauty and appalling subject matter in his work draws us in and then knocks us out. This experience parallels what he calls “the uneasy place we occupy”: we desire and demand material comfort but we also know that the impact of our overconsumption and over-population on the natural world is hugely destructive, “perhaps irreparably” so. Equally compelling in his art is his skilled register of both vast scale and extreme detail. Burtynsky’s use of a large format camera and, recently, a Hasselblaad with digital back-up means that an extraordinary degree of definition extends from the foreground to the far background, which does not necessarily include a horizon line. Part of the impact of his work is achieved by his high vantage point, which serves to engulf us in a scene whose beginning and end we can’t detect. Burtynsky’s art makes available to us not only landscapes that we urban, over-consumers never see but also a far greater degree of detail than our human eyes could process if we happened to be standing on the spot he was standing on. His images are hyper-rich, hyper-real and, ultimately, hyper-disturbing.

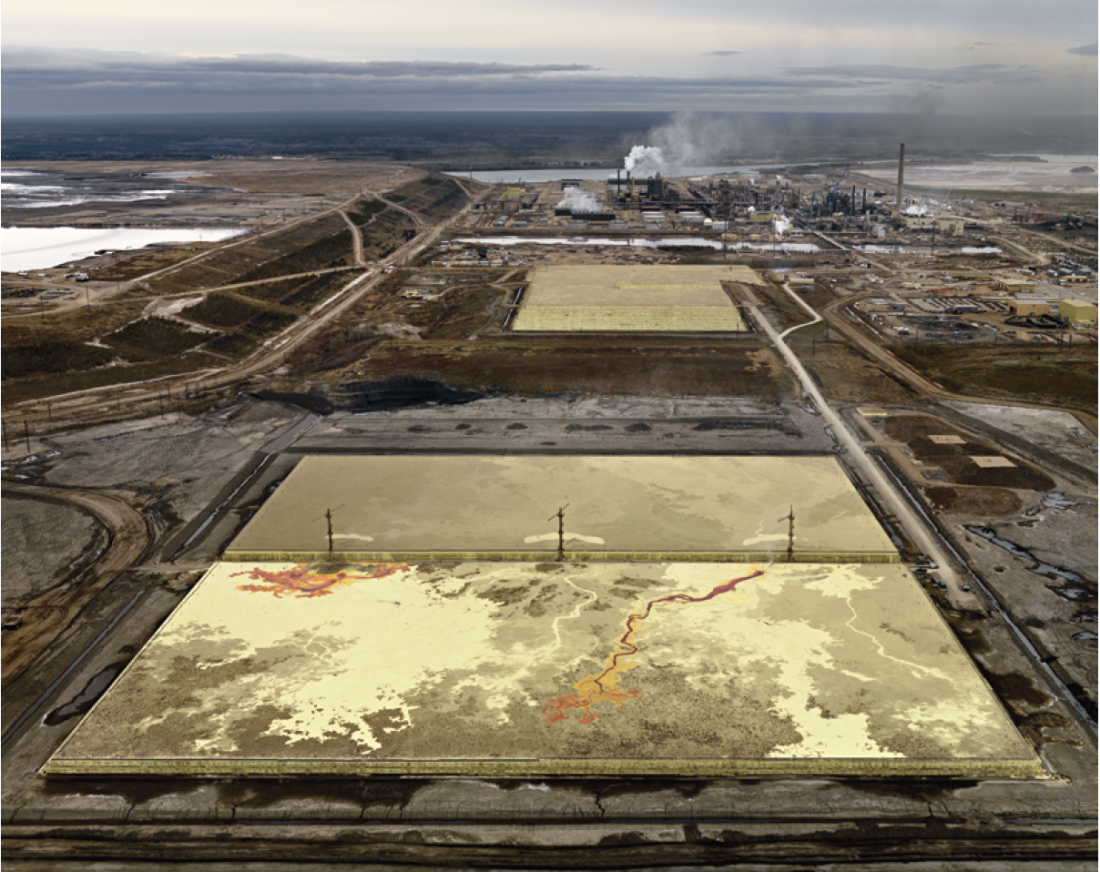

Edward Burtynsky, Alberta Oil Sands #2 – Fort McMurray, Alberta, 2007, chromogenic print on photographic paper, edition 2/6, 48 x 60”. Image copyright Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto, and Paul Kuhn Gallery, Calgary.

The earliest of the work on view, the “Homesteads” and “Railcuts,” were taken on a road trip in the mid-1980s when Burtynsky was defining his interest in the impact of “progress” on the landscape. Both series signify to Burtynsky the push westward—the conquest of nature, the taming of the wilderness—by waves of colonizers, but both are also more understated than the industrial landscapes we usually associate with him. In “Railcuts,” railway lines are depicted as thin, black, horizontal threads laid across the frame-filling faces of granitic mountains. These works seem to address the Romantic landscape tradition, in which nature far and fearfully overwhelms the human presence. Despite our historic knowledge of the engineering, particularly the blasting, that occurred in their construction, the train tracks and snow sheds look small and vulnerable against the enormity of the rock face.

Edward Burtynsky, Alberta Oil Sands #6 – Fort McMurray, Alberta, 2007, chromogenic print on photographic paper, edition 2/6, 48 x 60”. Image copyright Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto, and Paul Kuhn Gallery, Calgary.

The “Homesteads” series evokes the pastoral rather than Romantic landscape tradition. In one work, Homesteads #40 – Between Merritt & Princeton, Highway 5, British Columbia, an unpaved road winds through rolling hills of sagebrush and dry grass in the foreground, ending at a big, contemporary house in the middle ground. In the background, lush, green, irrigated fields reveal the ways in which humans have cultivated the land, overturning natural conditions to their advantage, at least in the short term. Subtle as it is, the incursion of the road into the rural landscape hints at the dependence of modern-day farmers and ranchers upon oil and automobiles and their—our— inexorable link with the globalized economy.

Edward Burtynsky, Oil Fields 25 – Fort McMurray, Alberta, 2001, chromogenic print on photographic paper, edition 4/5, 40 x 50”. Image copyright Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto, and Paul Kuhn Gallery, Calgary.

The link between globalization, the landscape of oil and the industrial sublime is perfectly realized in Burtynsky’s 2007 “Alberta Oil Sands” series. Again, the images employ a large scale and a calculated formal beauty to engage us in the controversial subject. Aerial shots taken in the Fort McMurray area, these works show us immense, alien landscapes stretching to the far, smoggy horizon. Filled with steam plants, tailing ponds, diverted waterways and uncountable square kilometres of ploughed-up earth, Burtynsky’s oil sands images confront us with a reality that most of us would prefer to deny. They also epitomize the industrial reversal of the romantic sublime. The terror we experience standing before this work is not from the 19th-century sense of ourselves as tiny and inconsequential in the face of an immense and unknowable universe, but rather from the realization of our astonishingly destructive powers. Burtynsky’s art shows us that we can level mountains, excavate craters the size of canyons and create vast lakes of toxic waste. Suddenly, the natural world seems small and vulnerable and humankind assumes the role of a violent and unappeasable god.❚

Edward Burtynsky: An Uneasy Beauty: Photographs of Western Canada was exhibited at the Surrey Art Gallery from January 17 to March 22, 2009.

Robin Laurence is a writer, curator and a Contributing Editor to Border Crossings from Vancouver.