Edmund Alleyn

The Edmund Alleyn retrospective at the Montreal Museum of Contemporary Art covers a comprehensive swath of the artist’s unique and idiosyncratic career. Alleyn was born in Quebec City in 1931 and passed away in Montreal in 2004. Curated by Mark Lanctôt, the show centres on Alleyn’s painting practice but also includes numerous works on paper in different media—sculptures, a video and several intermedia pieces, finding and pursuing a persuasive through-line that follows the artist’s progress from the 1950s to the early 2000s. There is also some supporting historical material in the exhibition as well as a finely informative documentary film downstairs in the foyer, called L’Atelier de mon pere/My Father’s Studio, by his daughter Jennifer Alleyn. This show accomplishes a difficult task to begin with, in executing a holistic installation of the work and productively arguing an overarching logic to and of Alleyn’s multivalent creative history. He was a protean artist, ever evolving and profoundly heterogeneous—he twisted and turned in multiple directions, producing results that were frequently virtuosic and somehow classical in composure and assurance, but also challengingly personal and expressively urgent, even esoteric in the breadth of his research. By turns acerbic and elegiac, tightly controlled and intuitively unfettered, Alleyn made a lot of very interesting work.

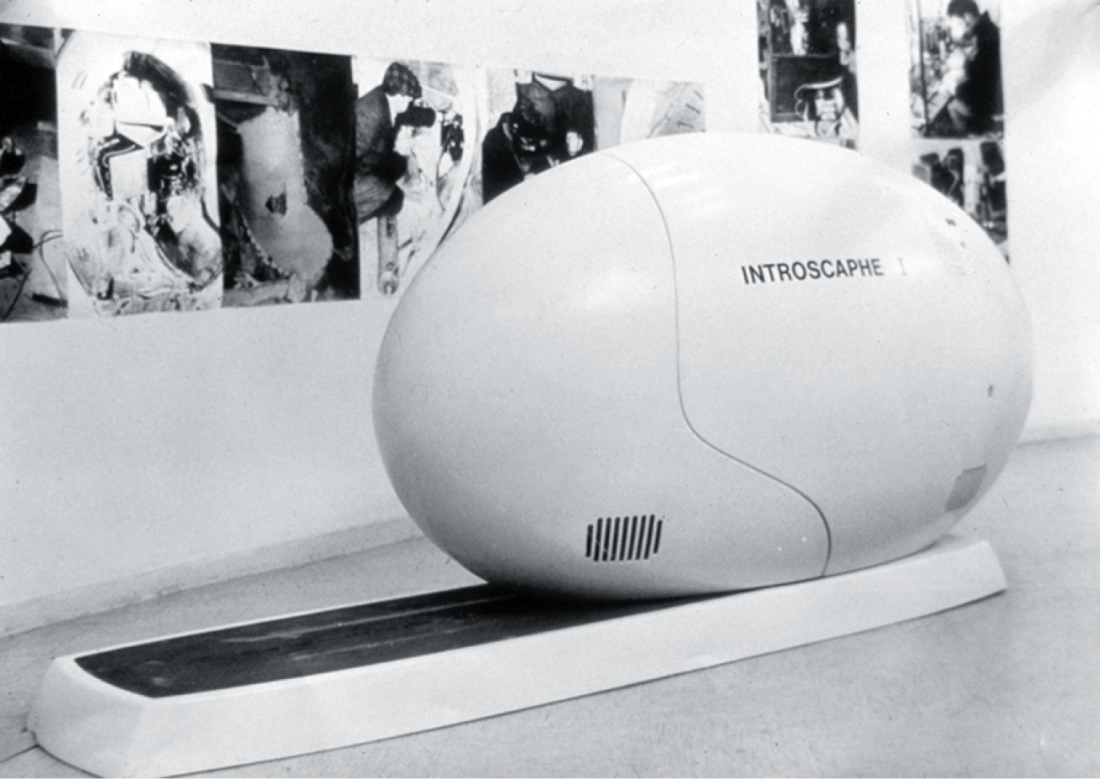

Edmund Alleyn, Introscaphe I, 1968–1970, wood, fibreglass, paint, electric and electronic circuits, projection system and other materials, 155 x 365 x 105 cm. Collection of the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec. Gift of Jennifer Alleyn. Courtesy Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

He moved to France in 1955 as a young man. Returning to Canada after 15 fairly successful years abroad, he became an influential professor at the University of Ottawa in 1972. He retired from teaching in 1991, but was extremely productive in the studio all his life, a tremendous, even obsessive maker and formal innovator in many respects, intellectually curious and restless. This show, which fully documents that restlessness and searching intelligence, is the first major overview of his work since his death. It reveals an artist who was in many ways ahead of his time, a prognosticator in a science fiction-like mould. If the exhibition has a centrepiece then it must be Introscaphe I from 1968–1970, into which Alleyn poured all of his resources, both imaginative and financial, producing a unique work in his oeuvre—in fact unique, period. It is a deceptively large, modishly utopian, oblong egg structure that lies open to reveal a cockpit-like space in which a single viewer could sit enclosed and be bombarded by part of Alleyn’s surreal ’60s film Alias, 1969 (exhibited full-length on a video screen in a separate room). It is now installed as a sculpture of sorts, remaining turned off, and is perhaps even more poignant in semi-retired dysfunction. It reads like a ghostly message sent from a possible future of the recent past, perhaps retrieved by archeology or from outer space. Alleyn’s imaginings, in all their forms, convey the sense of time’s wobble, that the future never really comes, just the past, which arrives with the present moment—while simultaneously generating the feeling that we have yet to entirely catch up to the most interesting ideas from 40 or 50 years ago.

Another standout piece is the awkwardly threatening sculpture The Old Seawolf from the early ’60s. Possessing a weird hybrid presence, its skeletal form and sickly colouration are both winning and seductive, while embodying a symbolically anthropomorphic figure of chaotic darkness and menacing conveyance. But it is in the exhibition’s paintings that the artist is most comprehensively represented. Alleyn’s work always generates a complex feeling of ubiquitous unease, a melancholy, as though every project he chose to do left him with a bad conscience towards all the other things he wasn’t undertaking as a result, an obsession with time, its passage and loss. Even his most pastoral scenes of family leisure and repose in the country are a touch sad, suffused with light and atmosphere that seems to be waning even at its brightest.

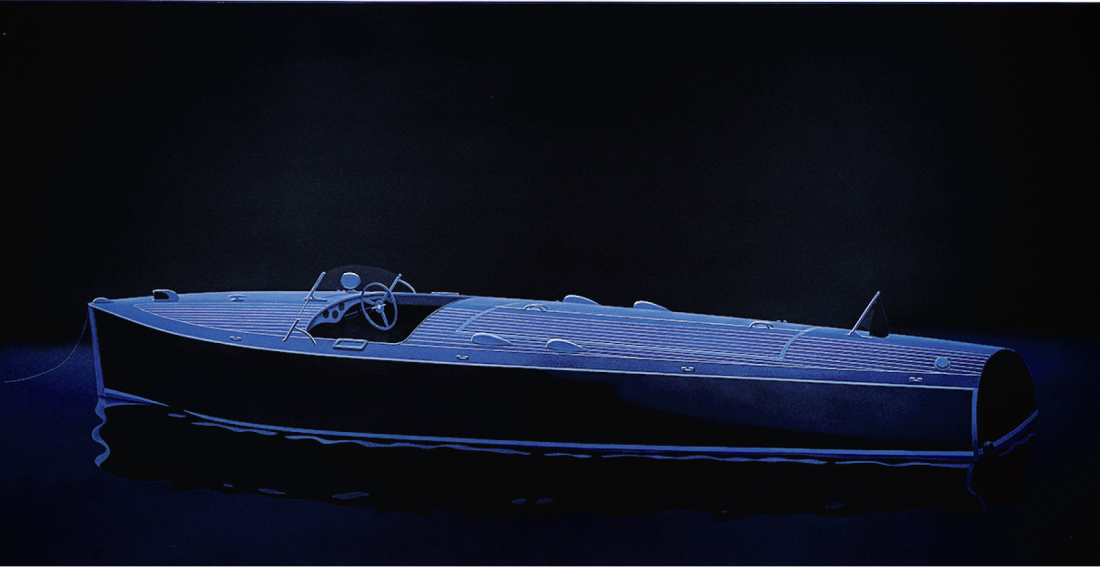

L’Invitation au voyage, 1989–1990, oil, alkyd resin on canvas, 236.5 x 467.5 cm. Collection of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Purchase, given by Horsley and Annie Townsend and the Arthur Lismer Fund.

His 1988 oil on canvas Edge of Silence depicts a vacant tennis court, laid out on the canvas like a nearly symmetrical, impeccable, post-painterly abstraction. Except, as our eyes acclimatize to the painting in an almost mimetic manner, as though we are there ourselves, outside at night, we become aware of the gorgeous painting-ness of the piece, the fluid, breathing surface and jewel-like colour. The borderline between abstraction and figuration has been made a great deal of, almost at times done to death as though it were the central concern of contemporary painting, and not a rhetorical convenience—but paintings like this forcefully bring home the issue of the formal versus the subjective, the manner in which the graphically ornamental or decorative and the putatively illustrative or anecdotal can elementally merge within painting’s compass. That Alleyn can do so in depicting a seemingly left-field subject like a tennis court is both particular and impressive, before it slowly dawns on the viewer that the tourney of to and fro in tennis, the process of hitting the ball back and forth, is possibly the perfect metaphor for exactly the elusive fusion of depiction and non-objectivity. It’s a quietly spectacular piece.

Another central gem of the show is L’invitation au voyage, probably the best known of all Alleyn’s paintings, but it feels like a new experience here. Another night piece, it is a massive canvas that has often been installed at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, in one or another of the permanent collection rooms. Known to many people as the “boat painting,” it is suffused with the feel of warm night-time, of the summer heat, of the hazy meaningfulness of watching the ebb and slosh of lake waters glimmering with reflections and semi-hidden meaningfulness. The boat is clearly supernatural in some way, although it utterly prevents our being able to say why on any closer examination; up close it immediately becomes formal and impersonal to look at. A piece this suggestive can only be made by a genuine seer, someone who uses a magic that is at once simple legerdemain but also transcends slight of hand to reveal something summoned, a kind of clairvoyance. ❚

“Edmund Alleyn: In my studio, I am many” is on exhibition at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal from May 19 to September 25, 2016.

Benjamin Klein is a Montreal-based artist, writer and independent curator.