Ed Pien

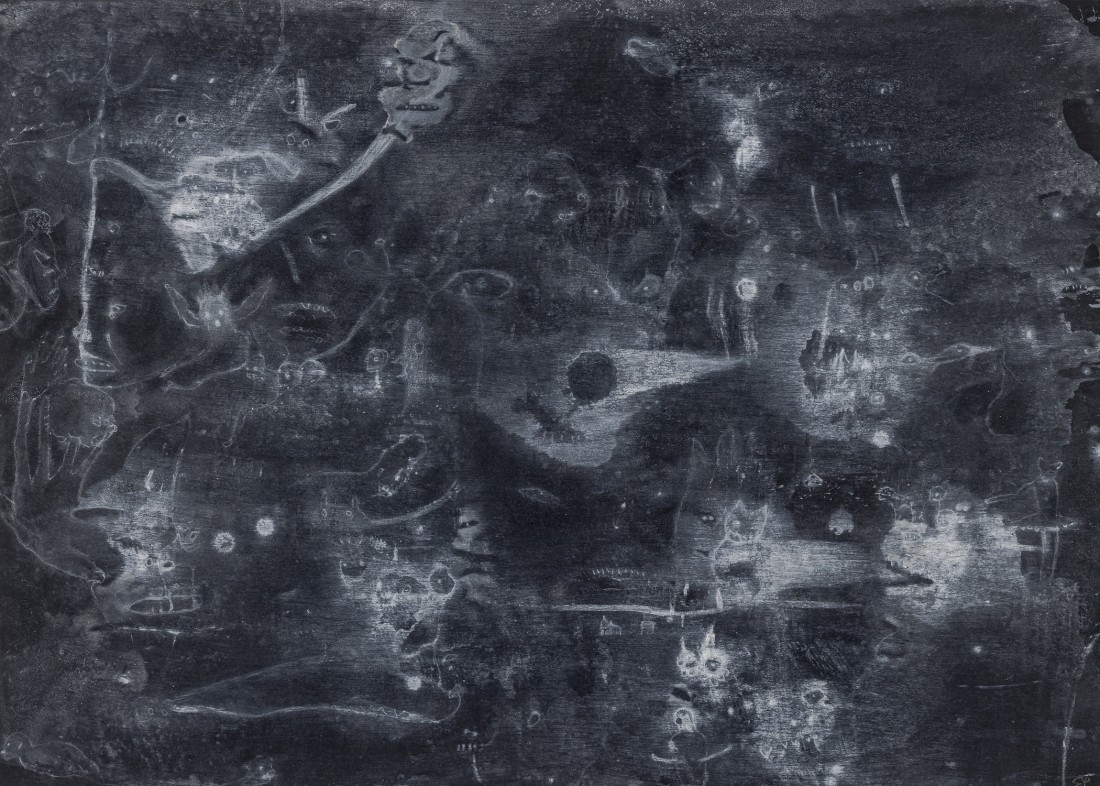

It is tempting to separate Ed Pien’s immersive installations, projections and wallsized drawings from his smaller works on paper, but the 26 ocean water drawings in his most recent exhibition at Birch Contemporary have a conceptual reach far beyond their modest scale. When I first went to the show, I walked straight to a relatively small figurative drawing that immediately resonates with Pien’s long-standing interest in otherworldly creatures and with my own art historical fascination with Bosch’s eccentric concoctions. Here on a piece of rectangular 11.65” x 16.5” black paper, the remains of ocean water and white ink generate a panoply of febrile lines and shadowy greys. Some of the patterns are the traces of dilution, evaporation and other more mysterious tactical manoeuvres in the ink; other elements, especially the sly eyes, reveal the artist’s hand. What we have here is a collaborative practice. As Pien states, “Ocean drawing is a series of works on paper that incorporates white ink mixed with ocean water. Ocean drawing presents my ongoing celebration of water’s sentience, that water has co-agency, creativity, and liveliness. This drawing collaboration shows the marks and images I make in responding to the images that water leaves as it escapes from the surface of my paper.” I will return to the political and aesthetic decision of not only attributing sentience to water but also recognizing its present and historical agency, but for the moment I want to go back to the aforementioned act of viewing. I was aware of the other drawings. I even took some of them in, but my attachment to the first drawing I encountered intensified. I started thinking of Bosch and then about the myriad ghosts I had seen in Pien’s other work. Former experiences of viewing came rushing back, affirming the sense that the process of world-making is always haunted by prior worlds. One drawing opened a channel to a host of other works seen in other places and other times.

Ed Pien, A Boschian Universe, 2018, ink and ocean water on black archival paper, 11.63 x 16.2 inches. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. Courtesy Birch Contemporary, Toronto.

Ed Pien, Reflections, 2018, ink and ocean water on black archival paper, 11.63 x 16.2 inches. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. Courtesy Birch Contemporary, Toronto.

When I returned to the show with an eye to reviewing it, I was more insistently aware that A Boschian Universe is part of a cluster of similar compositions. Myth World, Faeries Dreaming, The Seers and Ancient Creatures are dispersed carefully throughout the exhibition space to remind us that there are always already alternative worlds haunting this one. In this show the menagerie feels more vaguely northern European than some of Pien’s earlier explorations of Chinese and Asian ghosts, but I also began to suspect that this partitioning of traditions may be too much of this world. Within Pien’s practice all of these apparitions seem wellacquainted with each other. With the recognition of this cluster comes the realization that the entire show is built of sets of comparable drawings: some are adjacent to one another, most have migrated to other walls. There are a number of celestial spaces that remind me of Vija Celmins’s drawings of the night sky. Although Celmins is deeply invested in the stubborn magic of the real and Pien is explicitly welcoming places and figures beyond our ken, the comparison here is helpful because the evocation of the strangeness of space and the power of imagination is achieved through almost diametrically opposite means. Celmins manually evokes whites and greys from a black charcoal ground with erasers, but the telescopic photograph remains at hand; Pien, through the agency of the physical properties of salt water and ink, establishes the conditions for water to activate our visual memory of photographs of deep space. Interstellar, Celestial Clouds, Falling Star, Celestial Crown, Galactic Clouds, Nebulas and a pair of Sky Glyphs send me back to a set of Time-Life books on astronomy that I loved as a child. The “space” cluster is matched by another biomorphic set that almost indexically evokes forests of kelp and blooms of algae and plankton.

As the clusters proliferate, the worlds expand and start to overlap into a layered whole whose dimensions are unlimited. The bardo, the liminal world, deep space, the vast oceans, all surround and pass through us. The full import of this exhibition lies with the saline solution whose traces are before our eyes, the same solution that courses through our bodies, that sustains our planetary life, that is our constant companion. To use Pien’s term, salt water is not only a collaborator in the process of drawing, it is the collaborator in the process of living. And from that recognition a whole series of crucial political injunctions about the interconnectedness of aesthetic and political practice, human and non-human life, are realized. Accorded sentience, water knows this, and the drawings invite us to learn its mysterious ways. The subtle move here is that the ghosts that populate my favourite drawings in the show are no less beholden to the water. Because they encapsulate our fears and desires, these shadowy vestiges of the social currents that define us are left behind for our contemplation “when the water escapes.” Two sets of paired drawings make this manifest. In Gathering Souls and Gathering of Souls, grey oblong cells are arranged in columns and rows. For a poet like Emily Dickinson, who regularly passes from this life to the next, or for those trying to figure forth resting places for the children whose souls were abandoned by residential schools, there are little graves here. Hope seems to erupt from the white points of ink in the top rows of the former drawing while the latter seems to be still in a dormant state interrupted by horizontal strips of deposited salt. Likewise, in Luminous Bodies 1 myriad eyes transform the grey blobs into eerie revenants. The formally related Reflections eschews eyes for more geometric ovoids, and the revenants are gone. Except, when you step back you see that multiple blobs cohere into one fearsome ghost as if out of nowhere. Images emerge and fade, memories are blended and distilled, and the entire show affirms that the practice of drawing and viewing are suspended in one life-giving solution. ❚

“Ocean Drawings” was exhibited at Birch Contemporary, Toronto, from April 28, 2022, to June 4, 2022.

Daniel O’Quinn is a professor in the School of English and Theatre Studies at the University of Guelph