“Ecstasy: In and About Altered States”

The most inconspicuous object in the otherwise noisy and entertaining “Ecstasy: In and About Altered States” is a one-page document outlining a paseo by Belgian artist Francis Alÿs called Narcotourism, 1996. Alÿs describes a week-long experience of sampling a different intoxicant each day and its impact on his perceptions as he walked through an unnamed city. The project, writes Alÿs, is about “being physically present in a place while mentally elsewhere.” He describes the clumsiness of alcohol, the giggles of hashish, the paranoia of speed, the “inner warmth” of heroin, the auditory acuity of cocaine, the indifference of Valium, the “visual brightening and erotic impulses” of ecstasy. On the eighth day, and for several days thereafter, he rested in an involuntary depression.

It is this brief, chemical utopia of ecstasy, and its hidden dystopia, that is the inspiration for an exhibition that embraces the phenomenological and representational, grouping together 30 artists who dazzle and daze with works that tweak visual and auditory perception.

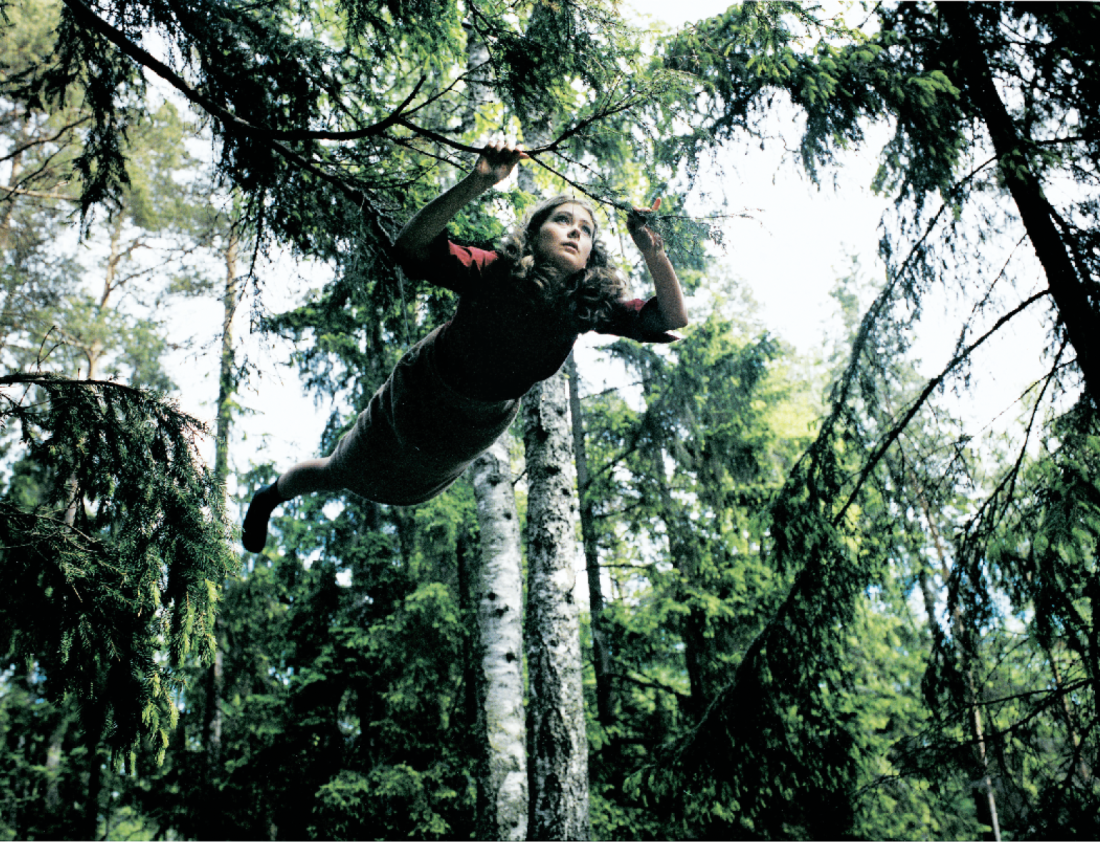

Eija-Liisa Ahtila, Talo/The House, (flying), 2002, joint acquisition of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and The Art Institute of Chicago.

But if Alÿs’s Narcotourism is a voyage of a solitude, the civic-minded German Klaus Weber proposes a communal equivalent in the form of a Victorian lead crystal fountain, which, according to a certificate of authenticity, gurgles with water spiked with potentized LSD “professionally prepared by a licensed homeopath,” tempting the viewer to commit the great museum no-no of dipping a finger into the flowing waters to verify the artist’s integrity and sample the enticements of an altered state. The fountain would be housed in a rectangular building constructed of one-way glass dropped over a city square, providing a safe haven in which to watch the world go by, as if on television.

Ideally, a museum is just such a container with its art as the vehicle for mind-expansion, and this exhibition is nothing if not a series of magic chambers, each offering its own enchantments. Massimo Bartolini confounds our most basic perceptions of space by rounding the corners of a brilliant white room, blurring the distinction between horizontal and vertical, anchoring the horizon with a glowing, highkey landscape painting in a gold frame, which pulses as if animated by video pixels. Danish-born Olafur Eliasson uses a blackened room to reverential effect, luring viewers into the dark by the sound and smell of falling water, where they stand clustered and hushed around a wet hearth of brightly illuminated raindrops falling into a trough. Ann Veronica Janssen’s Donut, 2003, flashes a white strobe in concentric rings in a pitch black box. The afterglow on the retina turns the eye into a projector of a phantom image. Erwin Redl uses a cavernous black space as the backdrop for a glittering array of tiny green LEDs suspended on vertical wires that place the viewer inside a virtual architecture of lines and vectors. These are all technological updatings of the light-and-space artists Robert Irwin and James Turrell, who thrived in Los Angeles in the 1960s.

Other room-sized installations encourage the lingering communal spirit of ecstasy, a drug engineered to produce an empathetic response. The collective, assume vivid astro focus, contributes a techno dance hall with mirrored floors, flashing lights, music and a model of a large female stripper spanning the room in a backbend, her bearded face pierced with needles. The atmosphere is a disco after the crowds have gone home, but one that remains bustling with the potential of ecstatic communion. A chain-mail curtain emblazoned with an image of the Pope blesses the transgressive sanctuary, the fertile ground of the creative process. Pierre Huyghe produces the aesthetic opposite in L’expédition scintillante, Acte 2 (light box), 2002, a dimly lit room with cushions on the floor, where visitors gather around a pair of white boxes, one suspended above the other, from which emanates a smoky light-show arranged to the gentle strains of Erik Satie, all setting the stage for a transcendent experience.

Pipilotte Rist, Related Legs (Yokohama Dandelions), detail, 2001, one mirror scanner and computerized control box, 2 DVD players, 1 audio system, steel cables, lace curtains, children’s chairs. Dimensions variable. Collection Adam Sender.

Rather than creating environments to alter the viewer’s perception, other artists such as Rodney Graham, shown in a Halcion-induced slumber, present filmed images of their intoxicated selves without letting the viewer in on the mysteries of their altered states. In contrast, Finnish artist Eija-Liisa Ahtila includes the viewer in the disorientating nature of psychotic perception. In Talo/The House, 2002, a three-panel video projection with a non-linear narrative, a woman haunted by the slippery boundaries between her inner and outer world narrates her predicament. Janet Cardiff’s and George Bures Miller’s The Muriel Lake Incident, 1999, shifts the viewer into an even more disorienting posture. With headphones attached to a 4- by-4-foot diorama of a miniature cinema, the audio places the viewer spatially in the seats, watching a film whose violent theme spills from the screen to the audience, neither of which is the space of the viewer who is in the museum, eavesdropping on both imaginary realities.

Other works are less intoxications than representations of intoxicants. Roxy Paine’s Psilocybe Cubensis Field, 1997, is a profusion of botanically correct mushrooms sprouting from the grey concrete floor, evoking the horror of biological creep—a possible hallucination of someone under the influence, or merely the mind-altering fungi run amok. Adjacent is Takashi Murikami’s Super Nova, 1999, a seven-panel painting of benign, brightly coloured anime mushrooms set against a metallic silver ground. These adorable fungi are less mushroom cloud—the image of apocalyptic defeat of the belligerent imperial nation—than the mushrooming effects of culturealtering post-war consumerism. A third mushroom piece, Carsten Höller’s Upside Down Mushroom Room, 2000, an inverted room with red and white mushrooms spinning from the ceiling, is a Go Ask Alice version of Alice in Wonderland.

Carsten Höller, Upside- Down Mushroom Room, 2000. Mushrooms: polystyrol, polyester, wood, paint, metal construction & electrical motors; ca. 9 revolutions per minute. Room: plasterboard, wood, neon lights, glass, acrylic paint, iron structure, 40 1/4 x 24 x 15 3/4”. All photographs courtesy Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, Los Angeles.

More literal still, Tom Friedman directs the mind-altering effects of obsessiveness toward a minuscule playdough rendition of the tiny time-release pills in a gelatin capsule. Fred Tomaselli exploits the pharmaceutical palette to eye-bending, rather than mind-bending, effect in his familiar but always dazzling resin-coated collages. The slick surface of the paintings offers the same promise of a bright shiny day as the pills locked inside.

“Ecstasy” makes a lively case for a generation of artists who embrace the controlled, plugged-in artifice required to produce a temporary transcendence amid the cacophony of the technological age. One cannot but wonder how much more captivating it might be if one were to dip a finger into Weber’s fountain. ■

“Ecstasy: In and About Altered States” was exhibited at the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, Los Angeles. It was organized by Paul Schimmel with the assistance of Gloria Sutton.

Susan Emerling is a writer living in Los Angeles. Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, ARTNEWS and Art in America. She is currently working on a collection of short fiction.