“Down Singing Centuries: Folk Literature of the Ukraine” translated by Florence Randall Livesay

Down Singing Centuries: Folk Literature of the Ukraine, compiled and edited by Louisa Loeb, with the assistance of Dorothy Livesay, is a collection of Ukrainian literature translated by the late Florence Randall Livesay. The book includes historical dumas (oral ballads), long works by Storozhenko and Ukrainka, a section on Ukrainian traditions, and a glowing essay on Florence Randall Livesay herself, outlining her work as a translator and as a “champion of Ukrainian culture.” The poems, tales, and descriptions are complemented by beautiful, colourful illustrations created by Stefan Czernecki: the result is an aesthetically exciting collection.

Florence Randall Livesay (1874-1953), of British descent, became intensively interested in Ukrainians and their culture at a time when most established Canadians were more hostile than friendly to the Ukrainian mass immigration. Initially unable to read Ukrainian, she made contact with Paul Crath, a Ukrainian intellectual, who provided her with literal translations of the poems and tales, translations which she rendered into poetic English. Eventually, she equipped herself with a reading knowledge of the language, although she never was able to speak it. Her first collection of folk tales, called Songs of Ukraine with Ruthenia Poems, was published in 1916; her repeated attempts; to have the rest of her translations published met with failure. It was only through Loeb’s extensive research, originally undertaken as a Ph.D. project, that the majority of Livesay’s work was rediscovered and published, bearing her envisioned title, Down Singing Centuries.

The translations, while generally interesting and enjoyable to read, are, at moments, weak and uneven. The dumas, originally spoken or sung, lose something through translation and through the act of confining them to written form. The individual poems included in the section entitled “Traditions and Folklore,” are often fresh and vital, as Livesay captures the emotion and spirit of the particular speaker:

I sat spinning, spinning, dead tired from the beginning—

Could I rest my weary head on my little white, low bed,

I might fall asleep.

Comes my husband’s mother (serpent, she—no other!)

‘Lazy girl, you good-for-naught! You don’t work! At last you’re caught!

All you want is sleep.’

Comes my husband’s father (comes the thunder, rather!)

And he roars: ‘You good-for-naught! You don’t work! At last you’re caught!

All you do is sleep.’

Came my lover like a dove, smiled and cooed with words of love

‘You must go to sleep.’ he said,

‘Far too young were you when wed,

You must go to sleep.’

I sat spinning, spinning…

The description of marriage customs, itself slightly patronizing, expresses too much amazement at the “quaint picturesqueness” of the ritual. Still, it contains a number of traditional ballads and songs which reveal a unity of theme and a clear sense of voice that is often lacking in other parts of the work. Ukrainka’s “Song of the Forest,” a strong, dynamic tale, is also beautifully translated, and Storozhenko’s “The Devil Fallen in Love” is the most exciting tale in the collection. Here Livesay’s gifts as a poet and translator are most noticeable; with a strong sense of both language and story, she captures the delightful mischieviousness of the work, recreating a unique, charming tale.

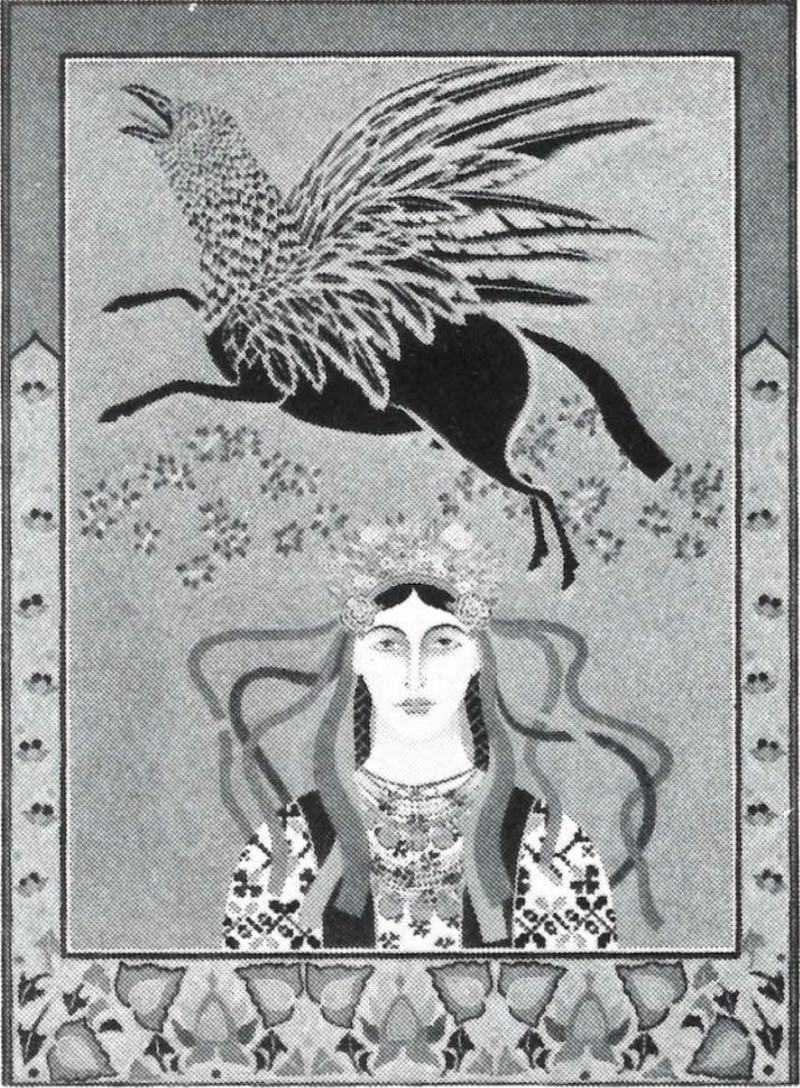

Czernecki’s illustrations, complementing the poems and tales, are exquisite. His intense, clear forms reveal the central meaning of the tales; his precise, vibrant colours evoke the movement held within them. The illustrations, celebrating the harmony of form and colour, add a dimension to the tales and to the collection as a whole, vitally expressing the mythic elements of this cultural, literary heritage.

Loeb’s final discussion, containing a biography of Livesay, and an extensive description of her interest in, and contributions to, Ukrainian culture, is informative, if somewhat gushy. Unfortunately, her insistence on portraying Livesay as a “champion” of Ukrainian culture underlines this gushiness, just as it serves to heighten the slight patronization found in some sections of the collection. Blinded by gratitude, Loeb refuses to recognize the voyeuristic quality that emerges from within the work and instead of exploring this, and working with the way Livesay’s biography relates to her art, she simply retreats into sentimentality. By ignoring the fact that Livesay was an outsider looking in and discovering a foreign culture, she dismisses the complexity of her personality, and in the process, does her a tremendous disservice.

At its best, Down Singing Centuries presents some remarkable tales and some gorgeous visual art. The book, as I suspect Livesay would wish, stands on its own. As a tribute to her life and work, it unwittingly expresses Livesay’s sincere discovery and poetic recreation of a foreign culture. In this respect, it is a beautiful book. ■

Kathie Kolybaba is the literary editor of Arts Manitoba.