Douglas Coupland

Few artists can claim as much accomplishment across as many disciplines as Douglas Coupland. A best-selling author whose first novel, Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture, 1991, defined the post-Boomer era, he has written some 16 books of fiction, 10 of non-fiction, and 7 screenplays, together with a swarm of essays, articles, lectures and opinion pieces. He is an award-winning designer of everything from furniture and accessories to parks and pop-up boutiques, and in recent years he has distinguished himself as a sculptor of great wit, with a number of public art commissions across Canada. Since 2000, as his Vancouver Art Gallery exhibition demonstrates, he has also appended painter, printmaker, photographer, collagist, assemblagist and installation artist to his CV.

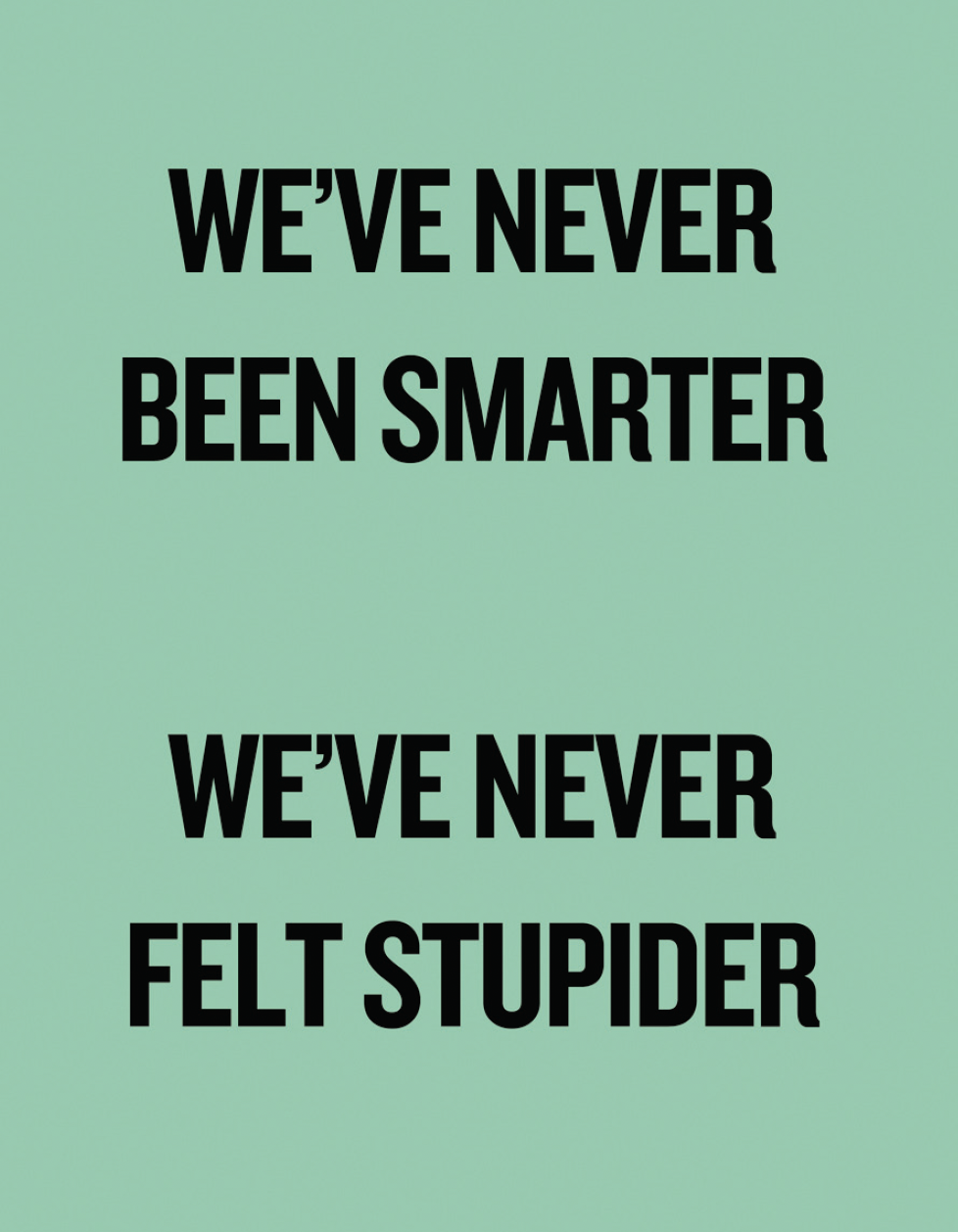

The binding thread in this immense range of expression is Coupland’s compelling ability to identify and describe our contemporary condition. He is one of the most astute social commentators of our day. As with his fiction, his art reveals he is particularly gifted at recognizing, before anyone else it seems, the latest idioms of popular culture and the most recent manifestations of digital technology, especially as they shape our understanding, not only of the world but of ourselves. (Underscoring all this is the contention that computers are reconfiguring our thought processes.) The show’s subtitle, “everywhere is anywhere is anything is everything,” suggests Coupland’s take on globalization, social media and ubiquitous digital culture—and the way they compress time and space. Utopia, dystopia and post-war modernist architecture, along with national identity, terrorism, government surveillance, socio-economic inequities, environmental degradation and the power of language, are also thematic strands that run through this big and diverse 15-year survey. Despite its bright colours, clean lines, shiny surfaces, humorous aphorisms and seemingly upbeat orientation towards children’s toys, the show does much grappling with the dark and the dire.

Douglas Coupland, Brilliant Information Overload Pop Head, 2010, acrylic and epoxy on pigment print. Collection Lucia Haugen Lundin, Courtesy Vancouver Art Gallery.

A great admirer of Andy Warhol, whom he directly acknowledges in his framed series of fur and nylon, Wigs in the Style of Andy Warhol (slightly creepy, they’re reminiscent of large, hairy, biological specimens—or worse, human scalps—pressed under glass), Coupland is in many ways a Pop artist for the 21st century. He is immensely alert to the tropes of contemporary consumerism, as is evident in the oversized and unlabelled but still familiar plastic containers and the QR code paintings in the section of the show titled “The Pop Explosion.” Tokyo Harbour, an assemblage comprising 108 bottles for (but emptied of) Japanese housecleaning products, reflects not only the artist’s simple, design-based delight in their appearance but also his fondness for the country and culture of Japan, where he has spent time studying, working and deeply observing. Coupland also mimics Roy Lichtenstein in paintings like Better Living through Windows and Mirror No.1, drawing formal parallels between the dot-matrix printing techniques of the 1960s, which Lichtenstein so effectively enlarged and exaggerated, and the accommodating pixels of contemporary computer-generated imagery.

Coupland’s approach to information technologies and social media is equal parts fluent and ambivalent. (The most popular word painting in his show is probably “I miss my pre-Internet brain.”) On the one hand, he ably employs digital tools and references. On the other hand, his work is firmly lodged in the material realm. Still, when read through viewers’ cellphones, his colourful QR code paintings communicate messages to viewers. In the section titled “The 21st Century Condition,” his series of Op-art- esque paintings—seemingly abstract compositions of black dots on white grounds—make sense, that is, become representational when viewed through the lens of a smartphone or tablet. They’re hugely pixelated images of people falling or jumping to their deaths from the World Trade Center towers on September 11, 2001, and they reflect not only upon how that tragic day is burned into our collective memory but also the now ubiquitous processing of emotional experience through handheld digital devices. (Coupland has remarked, too, that had smartphones been invented before rather than after 9/11, we would have had a myriad of photographs of the first plane hitting the twin towers, rather than the scant few that incidentally came into being.)

Despite his able use of and articulate reflections upon contemporary technologies, Coupland is not what you would describe as a “computer artist.” (Kyra Kordoski’s review of Coupland’s show in Whitehot Magazine is particularly astute and probing on this point.) He is a maker and assembler of things, a believer in the histories that objects carry with them. In an Art Forum interview, he said, “There’s an enormous amount of stuff in the show. Density and strategies for accumulation are very important to me.” Certainly, his art confirms that he is an extreme collector, perhaps edging towards the hoarding end of the collecting spectrum. (In this, he resembles Warhol.) Still, he puts the thousands of things he intuitively gathers together to far better use than any of the hoarders you see on TV—those anxious and depressed individuals with newspapers piled to the ceiling and dead cats rotting within impenetrable heaps of cardboard boxes, telephone books, shopping bags, margarine containers, tin cans, torn clothing, broken furniture, unopened mail, automobile parts and black mould. Coupland has an uncanny knack for converting his collecting compulsions into fascinating installations.

Slogans for the 21st Century, 2011–2014 (detail), pigment prints on watercolour paper, laminated onto aluminium.

Some of his found objects are vintage, others are new, some banal, others collectable and all are reimagined through art. In the section titled “Growing Up Utopian,” for instance, countless Lego sets have been assembled to realize the once-and-future shape of our built environment. In The Brick Wall, a kind of three- dimensional mural has been created out of hundreds of pieces from various toy and construction sets, such as Duplo, Fiddlestix, Playskool, and Tinkertoys. Writing in the show’s accompanying monograph, the Vancouver Art Gallery’s Daina Augaitis asserts that “simply shaped and brightly coloured cubes, poles, spheres and other types of blocks lie waiting, poised for action in the work of constructing a new world.”

In the section of the show titled “Secret Handshake,” Coupland’s paradoxically fond and satirical reading of Canadian identity (which also includes geometricized reworkings of iconic paintings by Emily Carr and the Group of Seven), plywood shelves are lined with dozens and dozens of consumer items particular to us. Hockey masks, hockey pucks, a box of Kraft Dinner, a can of Pacific evaporated milk, a Crown Royal bag, an Ookpik, a miniature kayak, a miniature snowshoe, a miniature seal pup on a miniature ice floe, an old Royal Bank of Canada calendar, all function like the words and idioms that Canadians use and understand but Americans do not. Hutches placed throughout the Canadiana-themed galleries (which evolved out of Coupland’s 2003 installation, Canada House, and his photoessay books, Souvenir of Canada and its sequel) are constructed out of everything from Ontario highway road signs to Japanese tsunami debris washed ashore on Canada’s West Coast. Natural and political disasters speak through a scaled-down sculpture of a collapsed hydro tower (ice storm) and a charred and broken model of the CN Tower (Rob Ford).

Coupland’s collecting habits are most conspicuously revealed in his “still life” installation, The Brain, a vividly imagined cabinet of curiosities that includes considered arrangements of found and altered objects that the artist has been collecting—without fully understanding why—for some 15 years. Included here are plastic fruits, vegetables, ice cream cones and corporate mascots, and miniature plastic horses, dogs, trees, cars, soldiers and robots together with ceramic bowls, vases, fish, seashells and hillbilly figurines, and a Japanese screen, a faux- colonial rocking chair, a tree stump, tatami mats, links of German sausage, two underwear mannequins and a make-up mirror. The Brain is, of course, Coupland’s brain, organized to represent his memories, dreams, desires, reflections, nightmares, neuronal impulses and the childhood seeds of the artist he would become. It is a visually intriguing exercise in autobiography and at the same time (although perhaps subtextually) speaks to the ways in which we define ourselves through material objects. This work is not about conspicuous consumption—not about collecting valuable objects like art and antiques and vintage cars—yet it still suggests how we as a society attach meaning to having rather than being. As Randy Frost and Gail Steketee observe in Compulsive Hoarding and the Meaning of Things, the pathological collecting and hoarding habits of individuals can be seen as a function of the overarching commercialization of culture and society’s potentially planet-destroying drive to over-consume. The personal was never more political. ❚

“Douglas Coupland: everywhere is anywhere is anything is everything” was exhibited at the Vancouver Art Gallery from May 31 to September 1, 2014. It will appear in Toronto at the Royal Ontario Museum from January 31 to April 26, 2015 and at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art from January 31 to April 19, 2015.

Robin Laurence is a Vancouver-based writer, curator and Contributing Editor to Border Crossings.