Dorothy Knowles

“Asked to draw a man, a house, a tree,” writes art historian Max J Friedlander in his unfailingly stimulating book, Landscape, Portrait, Still-Life: Their Origin and Development (Oxford: Bruno Cassirer, 1949), “a child will set to work without misgiving … If, on the other hand,” he continues, “I ask the child to draw a bit of country, it will get all confused and fail.” This, Friedlander claims, is because, on “the primitive level,” art is absolutely restricted to “isolated things.” And of course the “things” of landscape, the objects and passages making up “a bit of country,” are not isolated things but are all relational and busy with elision. Landscape is about accumulation, about what Friedlander calls “details arranged according to space-logic.”

This enjoyable exhibition by veteran painter Dorothy Knowles (the artist is now 82) is called “A Sense of Place.” “A sense of place has always been important to me,” Knowles is quoted as saying in the show’s catalogue and “is also important to my audience. People connect with and are curious about the location of the images in my paintings.”

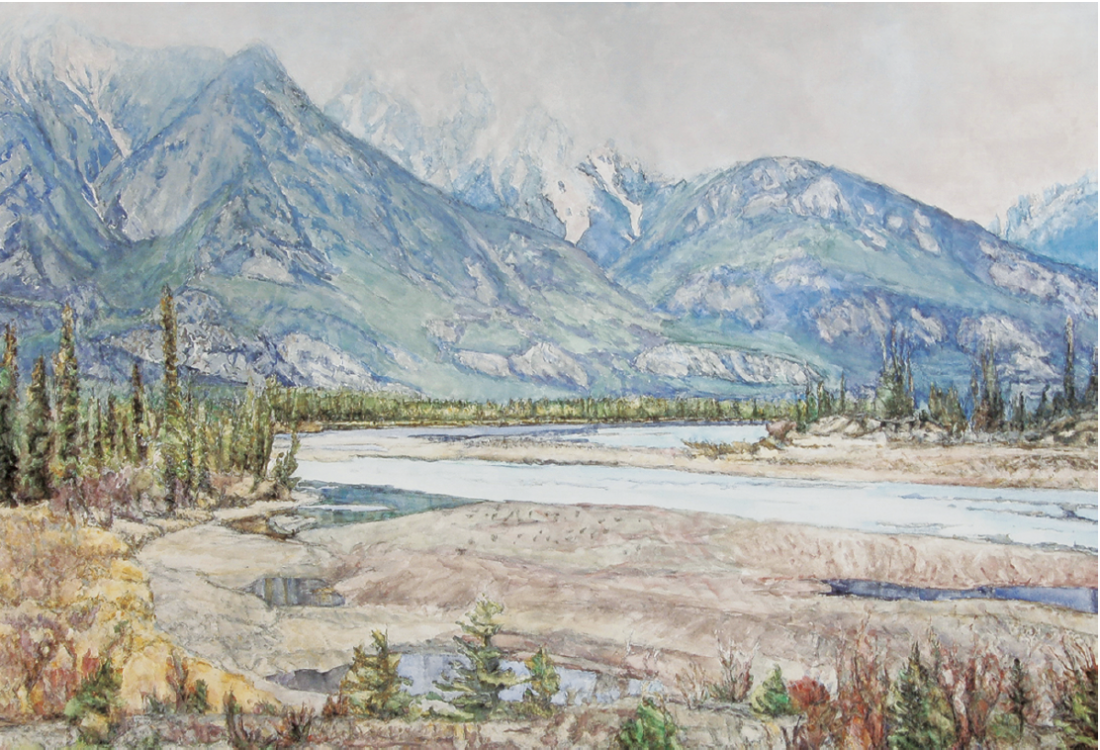

Dorothy Knowles, Clouds Touching the Mountains (AC-002-08), 2008, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 72”. Courtesy Miriam Shiell Fine Art, Toronto.

I am not one of those curious people. My delight in Knowles’s landscape painting—and surely this is true of a great number of her admirers—lies in her delicate disposition of incident and void, of her bestowing upon paper or canvas radiance, effulgence, and its strategic withdrawal or withholding. The paintings in this particular exhibition, unlike those generated by her usual forays into northern Saskatchewan, are, for the most part, painterly evocations of Tofino, British Columbia, but it wouldn’t matter much to me if they were from studies of the mountain landscapes of Tibet or the interlacing flora of the Brazilian rainforests: it is what Knowles offers the eye that counts. Furthermore, if Knowles can convince me that what she is looking at is what she sees, then I too can afford to give myself up to her chosen sense of place without ever wanting to trek there myself. As Samuel Butler reminds us in his Note-books (London: AC Fifield, 1913), in an entry called The Credulous Eye, “Painters should remember that the eye, as a general rule, is a good, simple, credulous organ—very ready to take things in trust if it be told them with any confidence of assertion.”

And Dorothy Knowles is all confidence of assertion. Some of her paintings—such as the fluttery Tangled Foreground—come perilously close to being busy and piecey, and yet never quite to the extent that they lose form and crumble into bits. Sometimes, as in the shorescape Lilies and Reeds, there doesn’t really seem to be enough going on at first to sustain the viewer’s interest. But then the work’s icy, all-pervasive grey-blue colour takes over and smoothes the ordinariness of the picture’s incidents into a muted tone poem about cool air and slow but unstoppable growth. This sense of anecdotal uneventfulness grows so forceful in exquisite little watercolours like Murray Point with a Strong West Wind and Reeds at Emma Lake that you begin to feel that Knowles is at her strongest when she is at her simplest. Indeed her paintings of—well, of nothing—seem downright profound in their openness and emptiness. In a brilliantly half-touched watercolour like A Sheltered Bay on a Windy Day, there is no landscape to look at (only a rudimentary far shore), no lakefront (it is the same colour as the sky), no Constable-interesting clouds. What you have here is only organized light, deftly applied by a woman who knows how.

Dorothy Knowles, Tofino Series #3 (AC-005-08), 2008, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 72”. Courtesy Miriam Shiell Fine Art, Toronto.

There are two large acrylic paintings in “A Sense of Place” that seem to me unusual not only in the Knowles canon but also in the realm of landscape painting generally. One is the remarkable Mountain Lake, which looks as if Knowles had dutifully painted the painting and then scoured most of it away so that it gleams with the muted ivory light of an old bone. The other is the majestic Tofino Series #3 in which a string of humped mountains in the background—though, in reality, nothing seems “behind” or “in front of” anything else—seem to have caught and are holding a soft, fading orange light. We view them through a delicately miasmic foreground—which is, again, not “before” anything—of line-thin twigs and branches, some of which bear spotty green leaves, sparsely organized bits of green punctuation that have a great deal more to do with the canny distribution of colour over the painting’s surface than they ever had to do with botany. Tofino Series #3 is a strange and masterful painting, awkward with relentless beauty, tireless and insinuating in its push-pull pictorial energies. “Sketching from nature,” writes Samuel Butler waggishly in Note-Books, “is very like trying to put a pinch of salt on her tail. And yet many manage to do it very nicely.” Dorothy Knowles manages it very nicely indeed. ❚

“Dorothy Knowles: A Sense of Place” was exhibited at Miriam Shiell Fine Art in Toronto from April 25 to May 23, 2009.

Gary Michael Dault is a critic, poet and painter who lives near Toronto.