Dorian Fitzgerald

I can think of few painting shows in which curatorial decisions on the part of the gallerist and painter contextualized the work so firmly and meaningfully within our culture and our universe that this placement resulted in an actual reduction of the significance of the work on display. Interestingly, this happened at the Clint Roenisch Gallery in April.

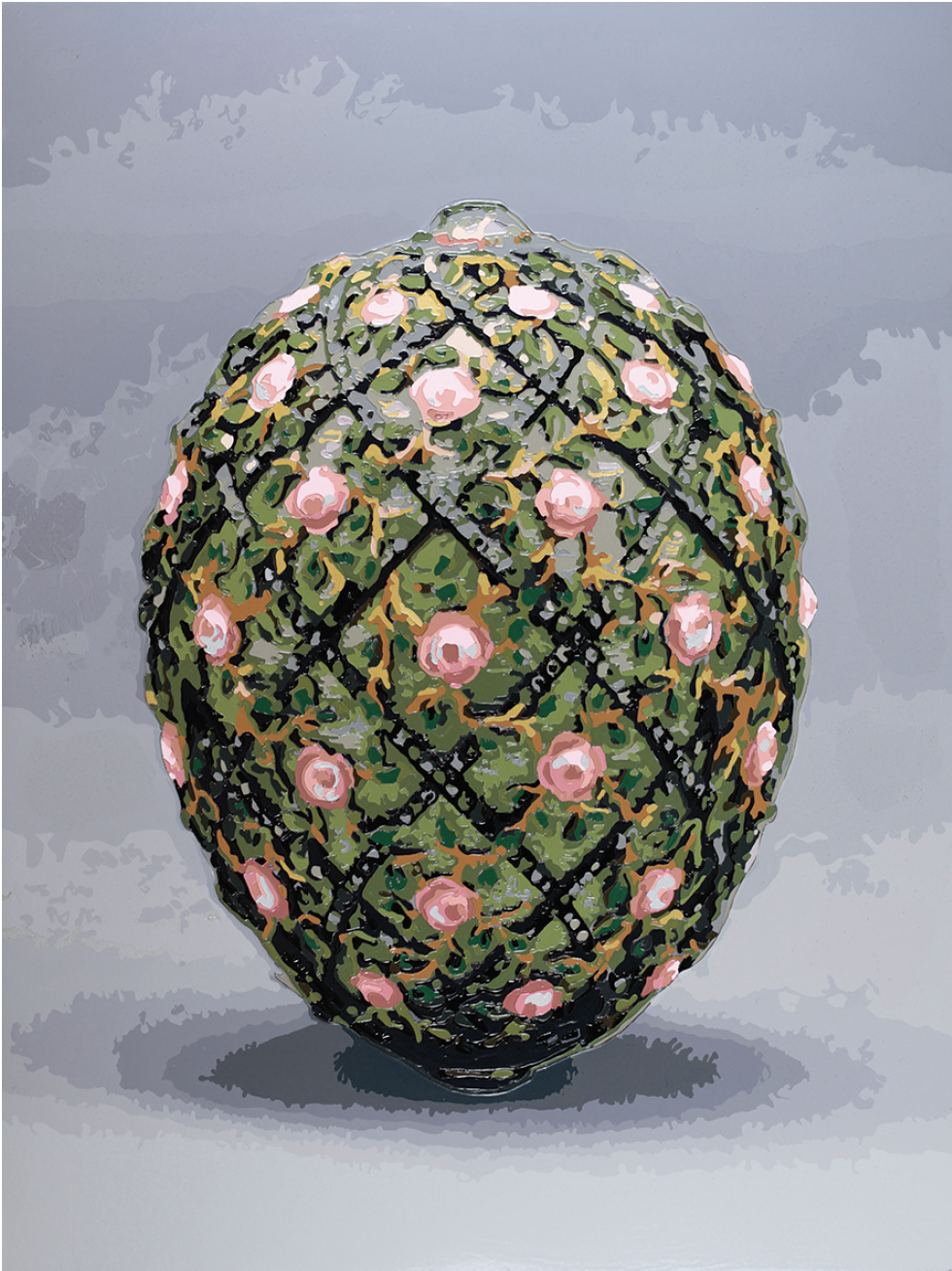

In the front room hung three of Dorian FitzGerald’s most recent large-scale paintings, one on each wall. Near the gallery’s front window was a depiction of a gold Cartier bracelet. Further back in the room, also on the west wall, was a large canvas portraying a Fabergé egg. Facing the egg, on the east wall, hung a nine-by-nine-foot depiction of the floor-to-ceiling display closet used by Elton John for his sunglasses, filled with his many colourful shades.

Dorian FitzGerald has an appealing and individual way of applying paint. He works from a photograph, first drawing a map that blocks off areas of colour, as in a paint-by-numbers book. Then he draws this map onto canvas using clear caulking, which raises itself about half a centimetre from the canvas, creating enclosed regions like a stained glass window before the glass is placed in. FitzGerald then pours paint into the enclosures and lets it set. The effect is somewhat sculptural, the small daubs of colour resolving into a comprehensible image only if the viewer stands far enough away.

In the back room was a large, wide, black-framed glossy print of the star-birthing region in our solar system known as the Eta Carinae Nebula NGC 3372—an image taken with the Hubble telescope that the artist found in an online databank, then digitally manipulated. In this piece, our universe appears magnificent, its beauty asymmetrical and completely mesmerizing. One could stare at it for hours and not begin to untangle its patterns. Orange and brown gases swirl like in a piece of marble. The area is dotted with stars. Some deep, incalculable harmony is being expressed—a beauty of far more complexity than the symmetrical, material objects portrayed in the front room.

It was gallery director Clint Roenisch’s idea to hang—on a nail on the south wall of the front room—FitzGerald’s soiled painting rag, crusted over with daubs of paint. This rag is reminiscent of props used in early studio photographs or 19th-century society portraits, in which the subject holds an object that symbolizes his or her work or hobby: a telescope, a violin. The addition of the rag transforms the show into a portrait of the artist—the rag being the object that best represents FitzGerald.

Dorian FitzGerald, Faberge Egg (Rose Trellis), 2010, acrylic and caulking on canvas mounted to board, 96 x 72”. Photograph: Toni Hafkensheid. Courtesy Clint Roenisch, Toronto.

It suggests that the artist, like the people who created the objects he is depicting, is part of the labouring, not leisure, class. And it comes as no surprise to learn that FitzGerald spends a long time making each work—his early paintings each took a year to complete. His process is precise and painstaking, as laboured as the production of a Fabergé egg. This perhaps says something about his lack of cynicism: he is making work he hopes will last. But a Fabergé egg is also meant to last and what does it mean for the present?

Expensive sunglasses, a Cartier bracelet—these are exquisite objects made with the primary intention of adorning the egos of their wealthy possessors—much like a painting sold in a gallery. FitzGerald’s status as just artist or craftsman is furthered by his artist’s statement in which he refers to himself as “a contemporary court painter, documenting on a grand scale the material and spatial excesses of our time.”

One might say of court painting, nice work if you can get it. But the photograph of the star-birthing region suggests that court painting is not such nice work. The universe outside the court possesses such profound and incomprehensible beauty that even the most imaginatively designed Cartier bracelet is no match for its wild magnificence, which—from the back room, just out of sight—mocks and minimizes the pretensions of the court objects.

If it weren’t for that photograph and rag, I might not have left the show wondering: why does the world need another court painter? And why has FitzGerald adopted this role? He was not appointed a court painter but, rather, made that choice. The material excesses of our time are already well documented. We all know the excesses of the rich are excessive.

What would FitzGerald—an obviously talented and ethically concerned individual—find if he ventured outside the court, into life’s more nebulous regions? It’s the right of even the most humble artist to paint what he, with his whole heart, finds worthy of our awe. ❚

“Dorian FitzGerald: Property of a Gentleman” was exhibited at Clint Roenisch in Toronto from March 12 to April 17, 2010.

Sheila Heti is the author of the forthcoming novel How Should a Person Be?, House of Anansi Press, Toronto.