Dive: David Diviney and Craig Le Blanc

Belgian artist Wim Delvoye describes the situation for male artists: it is, he suggests in Issue #96 of Border Crossings, “a bit like being a German. You’re not wrong, but maybe your father had been wrong.” Such a sentiment resonates for many young male artists dealing with a gallery community that is eager to redress the dead-white-male bias of past exhibition programming. By examining their patriarchal pasts, galleries hope to give voice to those previously ignored, but there are others who benefit: live, white, male artists, like David Diviney and Craig Le Blanc, who actively question what it means to be a young man in our society.

In their recent exhibition “Dive,” Diviney and Le Blanc negotiate the difficult terrain of contemporary masculinity with great wit and humour. Both artists make fabricated and found-object sculpture that incorporates imagery and objects associated with the hyper-masculine. Diviney draws inspiration from the rural middle- American world of hunting, gun culture and backwoods makeshift invention, while Leblanc uses hightech industry’s standard techniques to create enigmatic objects that reveal the profound impact and deeper social and cultural meaning of professional competitive sport.

Le Blanc’s curious array of objects—Caught, a submarine trapped in a fishing net mounted to a wooden trophy shield; The Medal Round, a diving board adorned with a medallion; The Mercy Rule, a corked circus daredevil cannon; and The High Dive, a high diving tower with a pint glass on the floor below—present an intentionally odd mix of scale. The small diving boards, submarine and cannon are contrasted with a real, functional fishing net, pint glass, rubber stopper and medallion. Rather than suggesting maquettes for larger works, Le Blanc’s work alludes to boyhood toys, models and trophies.

Craig Le Blanc, Caught, 2006, high density foam, walnut, fishing net, enamel, 8 x 30 x 17”. Photograph: M.K. Hutchinson, courtesy the artist.

His focus on daredevil activities (high diving, playing human cannonball, etc.) specifically makes reference to young men’s inclination towards risk-taking behavior. The inclusion of dubious symbols of success in sport (the tawdry trophy-shop shield, ribbon and medallion) and the toy-like scale of the work suggests that, from an early age, boys are conditioned to observe and emulate sports stars and daredevil heroes. Le Blanc’s work slyly comments on the culture of commodified spectacles like monster trucks and ultimate fighting. Frustration and failure seems designed into the objects he’s made; corked cannons and diving boards towering over small beer glasses invite a strangely appropriate mix of Surrealist psychoanalysis and looney-tunes-type comedy.

If Le Blanc is overly influenced by Wile E. Coyote’s Acme catalogue, Diviney seems inspired by that same urge that compels hunters to attach antelope horns to stuffed jackrabbits and display them in local saloons. In Diviney’s capable hands, off-the-shelf plastic and galvanized-metal buckets, hunting decoys and cedar shingles are the raw materials for a kind of spontaneous backwoods aesthetic explosion. His choices of materials and fabrication methods are deceptively simple. Blue plastic buckets are transformed into “water.” A ski mask with an inventive application of construction adhesive glue becomes a knothole in a piece of “wood.” The humour is homespun, derived from the simple transformation of materials and from the fact that Diviney plays along with his own jest, and invites us to do the same. His “water” leaks out of buckets and splashes on the floor, while bucket holes can be stopped with a simple cork—but, as with Le Blanc’s cannon, one asks: For how long?

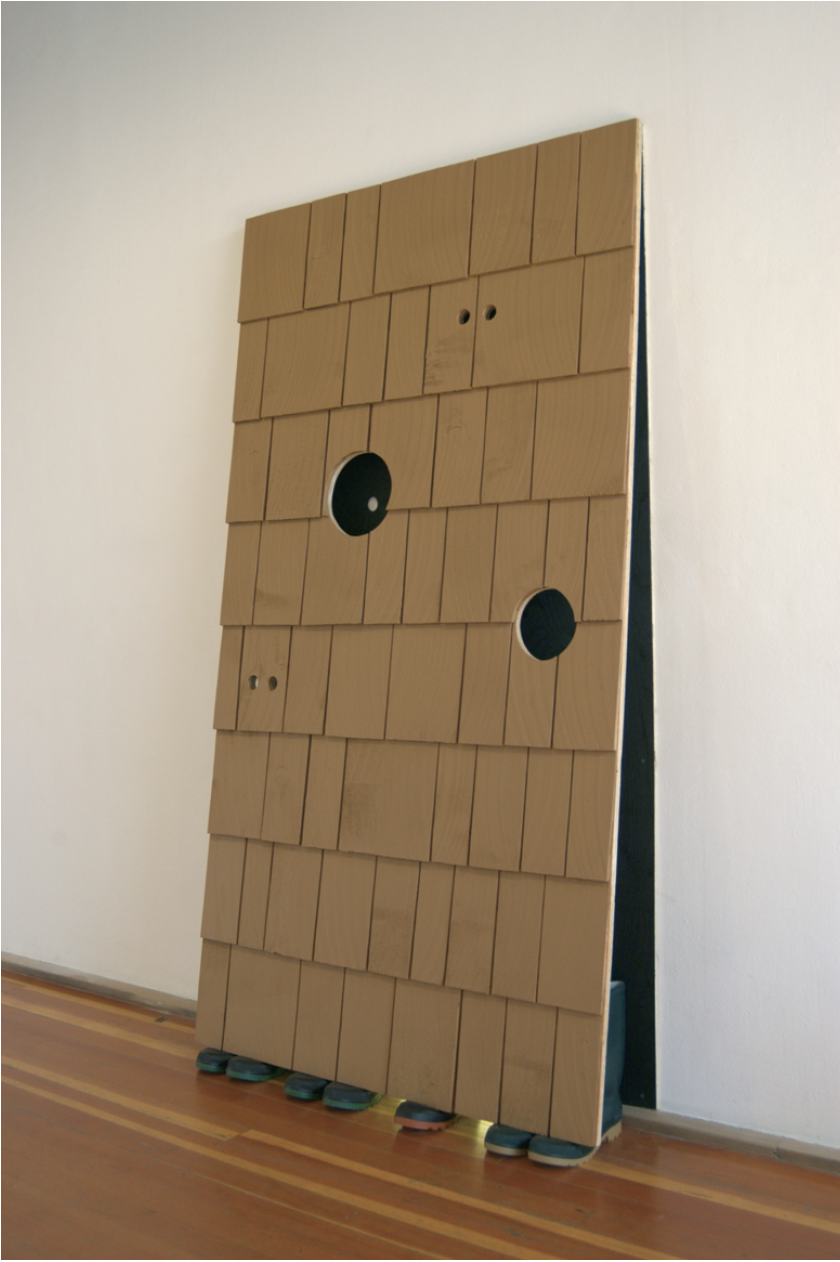

Diviney’s largest work, Blind, is a cedar-shingled panel penetrated by ominous, yet simultaneously comical, eyeholes. The toes of rubber boots or hunting hip waders stick out beneath the panel. The title Blind is a pun on the eyeholes and hunting blinds that hide the hunter from the game. Here, Diviney’s absent game or “trophy” is nicely contrasted with Le Blanc’s kitschy awards. There is the frightening (at best, Dick Cheney; at worst, Deliverance) prospect that the owners of these boots are armed. The work is edgy, but simultaneously manages to look like a three-dimensional version of the travelling-salesman-stays-the-night-in-the-barn type of joke.

David Diviney, Blind, 2006, plywood, cedar shingles, rubber boots. Photograph: Craig Le Blanc, courtesy the artist.

Diviney’s Decoy includes a plastic Canada goose cut in half and presented tail-up in a galvanized- metal tub of blue plaster “water.” The hollowness of the decoy is as obvious to viewers as it would be to any passing goose; but, more importantly, Decoy shares the same aesthetic as those backyard Madonnas displayed in makeshift bathtub mandorlas. Diviney challenges our stereotype that “jackelopes,” fences lined with bleach-bottle whirligigs and backyard shrines are the meaningless pastimes of trailer-park hillbillies with too much time on their hands, or lone neighbourhood kooks. For Diviney, backwoods crafts, folk art and their linguistic corollaries— from neighbourhood gossip to tall tales—are important symbols of culture, class and gender.

Though there is not collaboration in a conventional sense, there is a significant connection between Le Blanc and Diviney. Both use humour to disarm viewers and to better understand their own social role in regard to conventional masculine stereotypes. If you’re chuckling to yourself about those holes in the side of the duck blind, or what will happen when someone jumps from that high-dive platform, you’re not likely to call Diviney or Le Blanc “dirty macho patriarchs” (again quoting Delvoye), but what men do and how they do it are precisely the issues that are at stake in their work. ■

“Dive: David Diviney and Craig Le Blanc” was exhibited at Stride Gallery in Calgary from June 2 to July 1, 2006.

Blair Brennan combines his writing and art practice from his home in Edmonton.