Dil Hildebrand

The paintings in Dil Hildebrand’s exhibition “Peepshow,” shown last fall in Montreal, have lost nothing of the dazzling illusionism that brought the painter to fame while he was still in graduate school. But the baroque excessiveness of his earlier paintings is toned down in this new series. Gone are the sheets of paint that he used to re-apply on the canvas as patches or drapery. Gone, too, is the unsettling piling up of surfaces and spaces, destroying and rebuilding motifs, mixing natural with artificial lights, transposing theatre into painting. The new paintings represent views of a single space, the artist’s studio. They are overlaid with a surface treatment of grid-like, transparent panes framed in thick, textural lines of paint in saturated colours.

Hildebrand’s previous work formed a play of misrepresentation, a mischievous untying and redrawing of lines that used to hold things together, things like nature and culture, insides and outsides…and painting. Meaning in these works was found not so much in the content as in the processes of transposing representational codes. Spinning ever further away from reality, the turmoil in these paintings reflected a general sense of the instability that prevails in contemporary art and life. At the same time, sfumato overlays of misty grays and pale blues stirred up a sense of mourning for the loss of coherence.

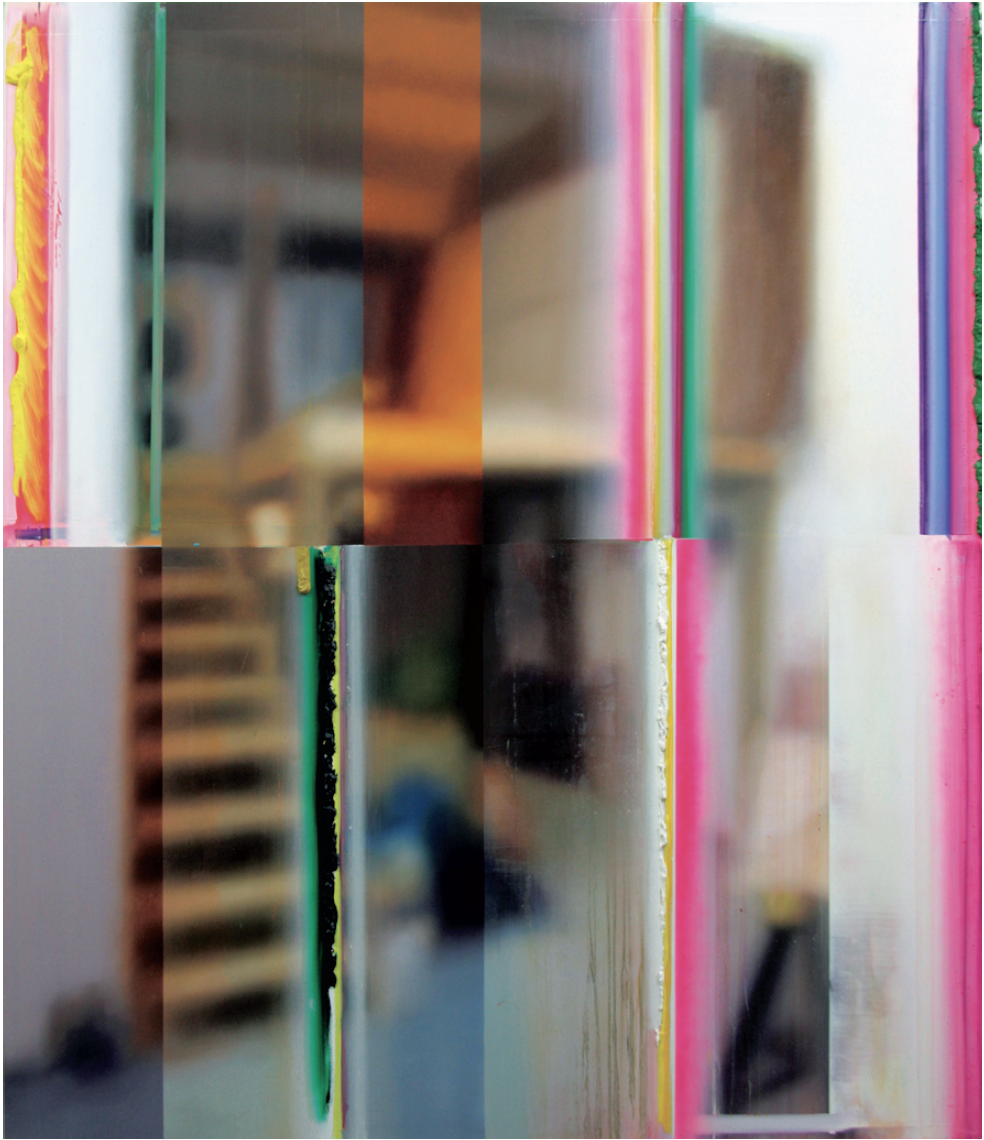

Dil Hildebrand, Studio D, 2010, oil on canvas, 213.5 x 183 cm. Courtesy Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain, Montreal, and the artist.

A feeling of loss persists in the new paintings, but the works in “Peepshow” are muted, simplified. Yearning for unity is brought into sharper focus within a rational, systematic inquiry into a single space, the artist’s studio. The exhibition shows this investigation in three components. The first gallery room is a modern white cube in which a series of large paintings show out-of-focus, photorealist depictions of a large, almost empty room. A painting easel and blank canvases set against the wall identify the space as an artist’s studio. Its bright starkness appears to emphasize the contemplative part of the painting process rather than its tactile, hands-on character. The life-size paintings feign to be an extension of real space, inviting the viewer to step out of the gallery and into the artist’s sanctum, this place of seclusion and reflection. Yet entry is barred by an over-painted, glass-like surface divided in grids. Squeegeed clean of thick paint that remains accumulated at the sides, this surface allows us only to peek in but not to enter.

The second component is a black-box gallery displaying a series of small paintings (30.5 by 26 centimetres) that look like sections of the larger ones and continue the theme of the artist’s studio. Brilliantly lit, the colourful canvases glow in the dark like so many plasma screens in a video installation. Here painting’s illusionism takes on the virtual reality of other, newer media. But the canvases’ tactile surfaces show paint’s skin-thin transparent layers as well as its globby viscosity—a reminder that, in its correspondences to the human body, painting always has an added value over new media.

A section of the darkened gallery shows the third component of the exhibition—a series of small charcoal drawings of intimate corners of the studio space, close-ups of tools and backs of canvases. These direct, naturalistic representations create a nostalgic homage to the age-old artisanal aspects of drawing and painting. Were it not for the large paint cans, the cart in one of the chiaroscuro drawings could come right out of a 19th-century studio. But here, too, we find references to painting’s 21st-century occupation of transposing representations from new media. Hildebrand sketched the drawings directly from life but made them appear to be copies of white-edged black-and-white photographs. And among the paper, paint and stretchers, we spot a digital projector case and filing cabinets presumably stuffed with source material.

Installation view of “Peepshow” at Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain in Montreal, 2010. Courtesy Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain, Montreal.

Much paint has been applied since 1656, when Diego Velazquez painted Las Meninas and let viewers peer into his palatial studio, and Hildebrand’s 2010 “Peepshow.” Velazquez’s masterpiece remains a testament to painting’s former status as a unique way of reflecting reality and to the power that the art of painting conferred on its masters. Hildebrand shows that the theme of the artist’s studio remains pertinent in a contemporary inquiry about painting’s relationship to reality. But painting, once the royalty of art, now intermingles with egalitarian modes of representation that no longer rely so much on an individual’s eye, brain and hand but on boxed devices, screens and millions of files and programs created by others. The power of the painter becomes ambiguous in this process.

I see a relationship, the more uncanny because it is probably unintentional, between Hildebrand’s drawing Sawhorses, 2010, and Rembrandt’s The Artist in his Studio, 1626–28, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Where Rembrandt places an empty canvas that appears to glow with possibilities, Hildebrand draws two sawhorses, indicating a less hallowed and less prescribed position for painting. Where Rembrandt puts himself in a dark corner of his studio contemplating the canvas, Hildebrand sets an empty chair. The studio remains, though the master has left. Yet, paradoxically, it is Hildebrand’s individual rendering talent, used so intelligently to question representation and reality in a digital age, that makes this exhibition so unforgettable. ❚

“Peepshow” was exhibited at Pierre-François Ouellette Art Contemporain in Montreal from September 9 to October 16, 2010.

Petra Halkes is a painter, curator and visual arts writer living in Ottawa.