Diana Thorneycroft

There is an old saying that wisdom often comes from the mouths of babes. No, not those “babes”—not the Pamela Lee Andersons of our popular culture, that’s just so much shapely hebephrenia—I mean the children. In the case of Diana Thorneycroft’s recent photographs, it issues forth from the mouths of worthier surrogates— plastic dolls—though wordless they are. Upon entering the space in which her “Doll Mouth” series was on exhibit, I literally caught my breath. The response was entirely appropriate to the work on exhibit. It was like entering, from the wings, a transgressive staging of Samuel Beckett’s Not I, a pretty transgressive play in its own right and one that had only one speaker: a disembodied mouth. We were transformed into a surrogate for the playwright’s auditor, and while there was no speaking voice to whom to make compassionate gestures, as there is in the play, the mouths of the dolls were still singularly eloquent, soaking wet cornucopias from which an endless stream of signifiers flooded our own eyes-and open mouths.

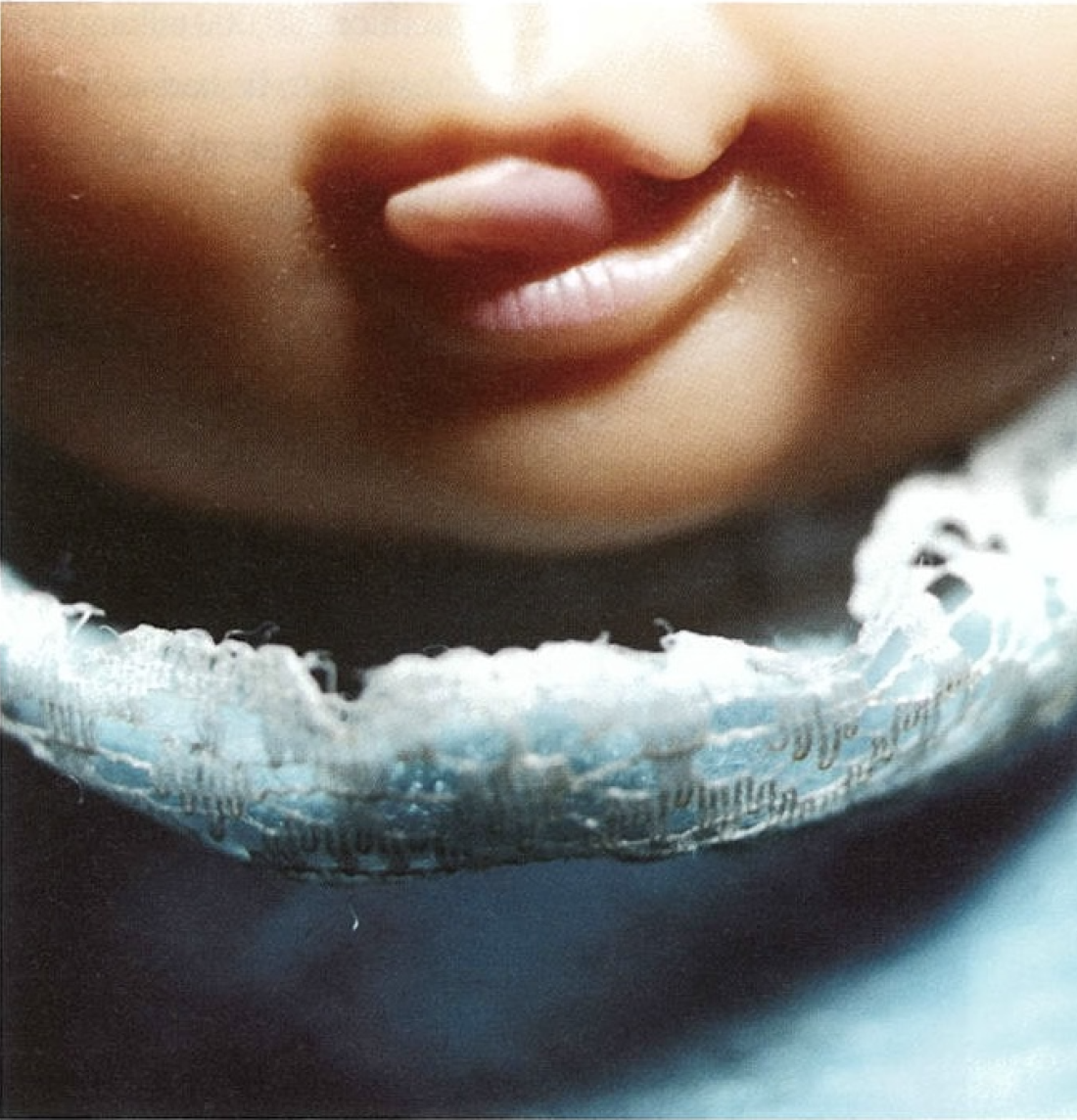

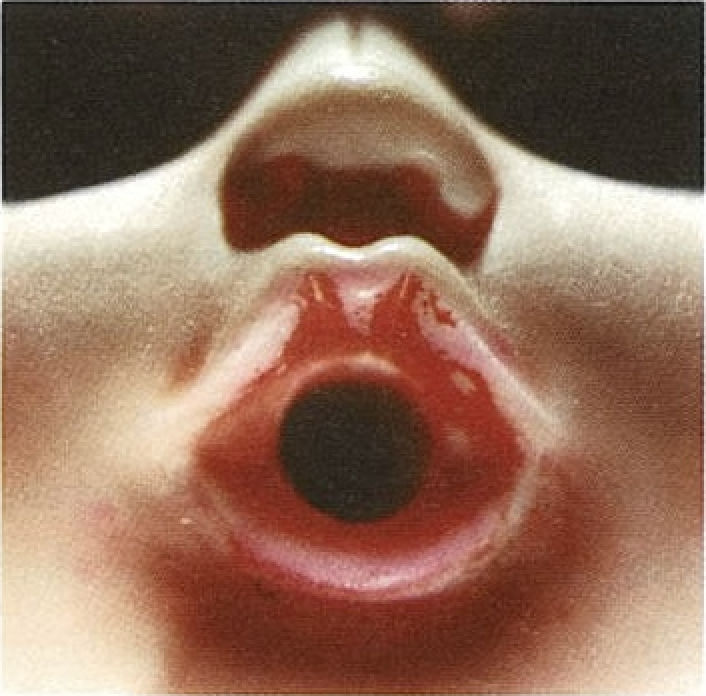

Closely cropped and unavoidably self-present, Thorneycroft’s Doll Mouth portraits are all about wetness. Whether puckered orifice, toothy smile or screaming hole, they are unnervingly, excruciatingly human—and all about alterity at its most liquid.

Seeing a choir of them reminded me that Kathy Acker once said: “Like the mouth, open and poised to speak, unable to make any sound, except to kiss.” Or spit, suck or slobber. But Acker’s is a better way of saying what a dearth of words are extant to express how disturbingly visceral and radically strange is Thorneycroft’s vision. Her use of photography to transmute a plastic doll into a human child is as radiant as it is harrowing. Why?

Diana Thorneycroft, Doll Mouth (little tongue), 2004, colour photograph, 71x 71 cm. Edition of 5. Photos courtesy Galerie Art Mûr, Montreal.

The open mouth is the ultimate membrane between an exorbitant exteriority and an equally exorbitant interiority. It is well known that infants are born with a sucking reflex—they instinctually suck for nourishment using their lips and jaw. (The lips of Thorneycroft’s dolls seem adorned with lip gloss, but that must be just a trick of the light.) Through the mouth we nourish ourselves and express feelings of love and sadness, anger and joy. It is also the orifice of utterance; though Thorneycroft’s dolls are silent, we imagine the screams, murmurs, hiccups and purrs they emit in doll land. As at least one commentator on Thorneycroft has said, and I think it true, the open doll mouth can be at least as complex as the human one. French philosopher Georges Bataille famously argued that all of human life is still bestially concentrated in the mouth. The mouths of Thorneycroft’s dolls here seem endlessly penetrable. Mute reservoirs, perhaps, but infinite registers of wholly human meaning. Thorneycroft’s is an interrogatory experiment without limits. She has never, not once, not ever, played it safe and winsome. And she does not here, in her “Doll Mouth” series, either.

The narrative voice of Sylvia Plath’s “Morning Song” came unbidden to the threshold of conscious thought as I stood there before them: haunted by the voice of a depressed, underwhelmed mother for whom her newborn infant is “like a fat gold watch.” Her baby’s mouth, “clean as a cat’s,” that “Whitens and swallows its dull stars.” The mouth of her newborn, eternally hungry, becomes an unforgiving orifice, indeed. We reflect on the sad and terrifying pathos that inflects the mother’s voice.

When Thorneycroft speaks of her encounter with the collector who owned the dolls, it sounds at once outlandishly episodic and pure serendipity, but then we reflect on how lightning-like her eye must surely have seen and seized what we see now: a brilliant metaphor, a harrowing humanness and the ever-present spectre of transgression.

Viewing these works means crossing into strange states, as Acker said, like laughter or love, well, strange laughter, indeed. I laughed at the self-consciousness of my response as I tried to impede a sense that these faces were somehow more, not less, than human, and, as I was transformed into their strange state, I caught the whiff of genuine uncanniness. Thorneycroft challenges us and invites us into open dialogue with our own presuppositions.

Diana Thorneycroft, Doll Mouth (black eyes), 2004, colour photograph, 71 x 71 cm. Edition of 5.

The attempt to make dolls increasingly humanoid has been going on throughout Modernity. Two 18th-century automatons were created by Frenchman Jacques de Vaucanson, one of them an automatonic duck that was capable of both eating and defecating. Then, there was Thomas Edison, whose attempts to create the first talking doll, aptly named Eve, were doomed to fail. (In the wake of successfully inventing both light bulb and phonograph, Edison tried to create a factory that could produce 100,000 talking Eves a year. Years later, he had sold only a paltry 294. Apparently, they were deemed by the wider public to be just plain “creepy.”)

It is startling to realize that Thorneycroft, using a simple Minolta camera in a darkened room, has made dolls more alarmingly lifelike than Jacques de Vaucanson’s, Edison’s stillborn Eve, those by today’s ingenious inventors with all manner of doll patents pending, and even those by computer Dollers earnestly at work to create the perfect computer doll across the vast breadth of the Net. We know that Thorneycroft uses no Web-enhanced technology or cybernetic tricks to “humanize” her dolls. She simply shot them in the dark—and they came undone.

The name of the other who challenges my preconceptions—and my unconscious—through the vehicle of the mouth here is phantasmatically written in light exposures: what seems like saliva or other ejecta is simply a fortuitous effect born of this tried and true technique. A photographer who is not afraid of the dark uses a plastic doll to test existing definitions of what it is to be human. This strange hybrid of the doll and the human is very disquieting, after all, and has ethical implications no sensitive observer could possibly ignore. Diana Thorneycroft’s reputation is as a fearless explorer of the dark side, and one utterly unafraid in her ongoing pursuit of issues of gender, childhood sexuality, the teachings of Father Freud and, more significantly, those of Julia Kristeva, memories real and suppressed, and the multifarious forces that mould our identities identities and the condition of being in an intersubjectively shared world.

Thorneycroft’s work, it has been suggested, prods the marrow of subconscious memory and desire. The “Doll Mouth” series marks her most courageous headlong flight into strangeness—and sameness, reminding us that, as the philosopher once said, a mouth may open for screams, cackles or speech, but the closed mouth—well, the closed mouth is at once beautiful and safe. Notably, the mouths of Thorneycroft’s dolls are mostly open. So, if the mouth is elsewhere understood as latent evidence of the animal nature of man, it is here, and most compellingly, evidence of the irreducibly human. ■

“The Doll Mouth Series” was exhibited at Galerie Art Mûr in Montreal from August 19 to September 23, 2006.

James Campbell is a writer and curator based in Montreal.