“Diabolique”

Given that curator Amanda Cachia was seeking to explore the impact of war and violence on the human psyche, it was not inappropriate that “Diabolique” was divided into two parts—“Diabolique i” and “ii,”—a function of logistics more than anything, in that the gallery couldn’t accommodate the work of all 22 artists at once. When we think of famous wars in recent history, the top two, both in terms of casualties suffered and money spent, are World Wars I and II.

Fawad Khan, Datsun Sunny Discordance, 2009, gouache, acrylic and ink on paper, 2 panels, each 40 x 60cm. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Cachia took the title for “Diabolique” from a classic 1955 French horror movie called Les Diaboliques that in English translates as “The Devils.” It may not have been intended, but a certain amount of irony attaches to that decision. Set in a French boarding school, the film sees the abused wife and mistress of the mean-spirited headmaster conspire to murder him. Things take a turn for the worse for the women when the man’s corpse mysteriously disappears from the pool they dumped it in to make his death look like an accident. Rarely when it comes to war and violence, are women thought of as perpetrators. That’s not to say that they don’t have blood on their hands, at least metaphorically. During WWI, for example, it was not uncommon for Canadian women to approach seemingly able-bodied men in civillian dress and strike them with powder puffs to mark them as cowards for not enlisting, as their own fathers, husbands and brothers had done. To the extent that war and other forms of state-sanctioned violence are typically used to gain and preserve privilege, women benefit just as much as men—even though it is men who have traditionally done the dirty work.

Douglas Coupland, The Gorgon, 2003, aluminum and fiberglass, 187 x 119 x 50 cm. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

That’s no longer true, of course. In modern armies (and police forces), women are on the front lines, just like men. That point is driven home in three photographs by Althea Thauberger that Cachia included in “Diabolique.” In March 2009, Thauberger travelled to Afghanistan under the Canadian Forces Artists Program, where she spent time with women stationed at Forward Operating Base Ma’Sum Ghar. Bleak doesn’t even begin to describe the landscape southwest of Khandahar City. True, the giant Canadian flag that “our” troops created by spray-painting gravel piled near the base is a nice touch. But otherwise, the area looks as hospitable as Mars. Afghanistan’s strategic value doesn’t lie in its topography, though. It’s alleged that, with its ties to Pakistan, it is a breeding ground for radical Islam. Although, as Rebecca Belmore suggests in a video documenting a March 2008 street performance she did in Vancouver called Making Always War, to sustain itself, the military-industrial complex is continually dredging up new bogeymen. National security is a legitimate concern, certainly, but it seems when nations invest heavily in the machinery of war, less weight is given to diplomacy in resolving disputes.

Following its Dunlop run, “Diabolique” will be exhibited at Montreal’s Galerie de l’UQAM from January 15 to February 13 and the Military Museums in Calgary July 22 to October 2, 2011. In curating the exhibition, Cachia, an Australian native who moved to Regina in 2007 from New York (in her catalogue essay, she recounts being in a midtown Manhattan hotel room when 9–11 occurred), has done an admirable job of addressing various facets of what undoubtedly is a complex human dynamic.

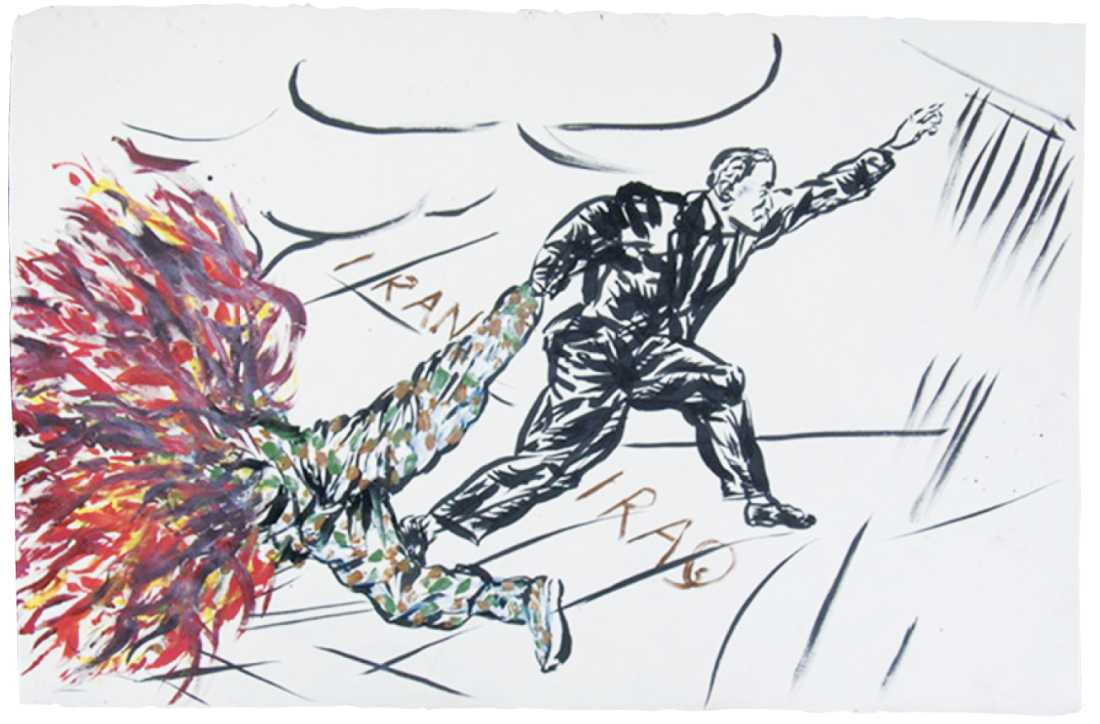

Raymond Pettibon, Untitled (Iran, Iraq), 2007, pen, ink and gouache on paper, 66.7 x 101.6 cm. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Technically, through our involvement in NATO’s International Security Assistance Force, Canada has been at war in Afghanistan for eight years. For the families and friends of soldiers stationed there, the war is very real. But for the rest of Canadians, it could be argued, it’s had negligible impact. Yes, we can watch the news reports, and perhaps even participate in the ceremonies that are held when the body of a fallen soldier is returned home for burial. But no bombs are exploding on the streets of Canadian cities. No armoured personnel carriers race through the countryside. No civilians are caught in the crossfire between soldiers and insurgents.

Through her judicious inclusion of artists with roots in countries with a history of regional conflict like Iran (Matilda Aslizadeh, Shirin Neshat), Romania (Bogdan Achimescu, Dan Perjovschi), Libya (Fawad Khan) and South Africa (William Kentridge), Cachia injects a visceral sense of the true toll war can take. In *stan, for instance, Achimescu presents hundreds of gestural portraits of nameless individuals strung from the ceiling of the adjacent library. Refugees? Victims of genocide buried in mass graves? Political prisoners “disappeared” by totalitarian regimes? Given the turbulent modern history of eastern Europe, all are valid readings.

Dana Claxton, Gunplay (Part Two), 2007, DVD 1:30, Video Still: courtesy of Video Out.

That’s not to say that war in some form doesn’t occur on Canadian soil every day. Class, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation—all, unfortunately, are battlegrounds where casualities are regularly incurred. It’s impossible to view Belmore’s performance video, for instance, without being reminded of our country’s sad history of colonization. That’s a theme David Garneau reinforces in his 2006 painting Evidence that uses as a base image an autopsy photo of 17-year-old Neil Stonechild, who died of exposure after being driven to the outskirts of Saskatoon and dropped off by police in November 1990.

Rather than focus on actual incidents of violent conflict, other artists explore the broader socio-cultural disconnect between our professed abhorrence of war and the many ways in which we glorify, even eroticize, it and condition youth to accept it as a normal part of life. In The Gorgon, 2003, Douglas Coupland, himself the son of a Canadian soldier, presents a human-size sculpture incorporating three green plastic toy soldiers that were once, and perhaps still are, a staple of every boy’s toy box. In four book works, Scott Waters augments the covers of Harlequin Romances with images of Harrier jets and Blackhawk helicopters to underscore the link between war/power and virility in patriarchal society.

Lest We Forget, indeed. ❚

“Diabolique: Part i” was exhibited at Dunlop Art Gallery in Regina from July 17 to August 30, 2009. “Diabolique: Part ii” was exhibited at Dunlop Art Gallery in Regina from September 4 to October 18, 2009.

Greg Beatty is a Regina-based writer with an interest in arts and culture who also works as a staff writer for the independent news magazine prairie dog.