Derek Sullivan

This past March the world lost one of its most innovative sculptors with the death of Richard Serra at age 85. Often enormous in scale, Serra’s sculptures are groundbreaking in how they shape interior spaces and interact with landscapes. In Canada Serra’s best-known sculpture is arguably Tilted Spheres in Terminal One at Toronto’s Pearson Airport. Installed in 2004, the sculpture consists of four free-standing, 12-foot-tall steel structures. An hour away, however, is Shift, a less-imposing Serra installation whose locale inspired Toronto-based Derek Sullivan’s recent exhibition, “Field Works.”

Created in the early 1970s, Shift is located on active farmland in Ontario’s King township. Consisting of six concrete slabs of varying lengths and heights embedded in a zigzag formation across the field, the work can’t be seen from any roads or neighbourhoods; reaching it requires a trek through forests and marshes. For Sullivan, however, the catalyst for “Field Works” was less Shift itself than the terrain in which it resides. (More information about the history of Shift can be found in “Richard Serra: Shift” by Heather Robinson in Border Crossings, Issue #93, 2005.)

Sullivan learned of Shift’s existence 25 years ago but didn’t try to find it until 2020. (Unlike some of us, he was successful on his first attempt.) He then visited the site every few weeks over the course of a year to document changes to the landscape and people’s presence within it over an extended period of time.

Derek Sullivan, installation view, “Field Works,” 2024, Susan Hobbs Gallery, Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. Courtesy Susan Hobbs Gallery, Toronto. Background left to right: #170, Field Publications, 2022–23, coloured pencil on Rising Museum Board, 133 × 102 centimetres; #169, Field Publications, 2022–23, coloured pencil on Rising Museum Board, 133 × 102 centimetres; Weathervane, 2008, metal, wood, paint, 37 × 70 × 68.5 centimetres. Foreground: Unfinished Sculpture, 2024, wood, compass, whistle, crystal, cord, 78 × 38 × 38 centimetres.

This aligns the drawings and sculptures in “Field Works” with artists like Richard Long, Nancy Holt and Hamish Fulton, whose practices often involve performative walks and prolonged engagements with a landscape. Sullivan’s projects are usually wide-ranging and research-based, encompassing broad interests such as modernist design, conceptual and abstract art practices and histories, book publishing, and systems of distribution and documentation. Sometimes Sullivan’s art can appear abstruse. On the surface “Field Works” looks and feels like his previous exhibitions, but, after spending time with it, one senses that something slightly different is happening; there is a feeling of openness, something less hermetic. Maybe this is because the locations from which Sullivan drew his inspiration and materials resonate with him on a more personal level: the Shift site is not far from where Sullivan grew up, the sculptures are made with material culled from a rural property he owns, and a mobile sculpture was produced in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, during a residency.

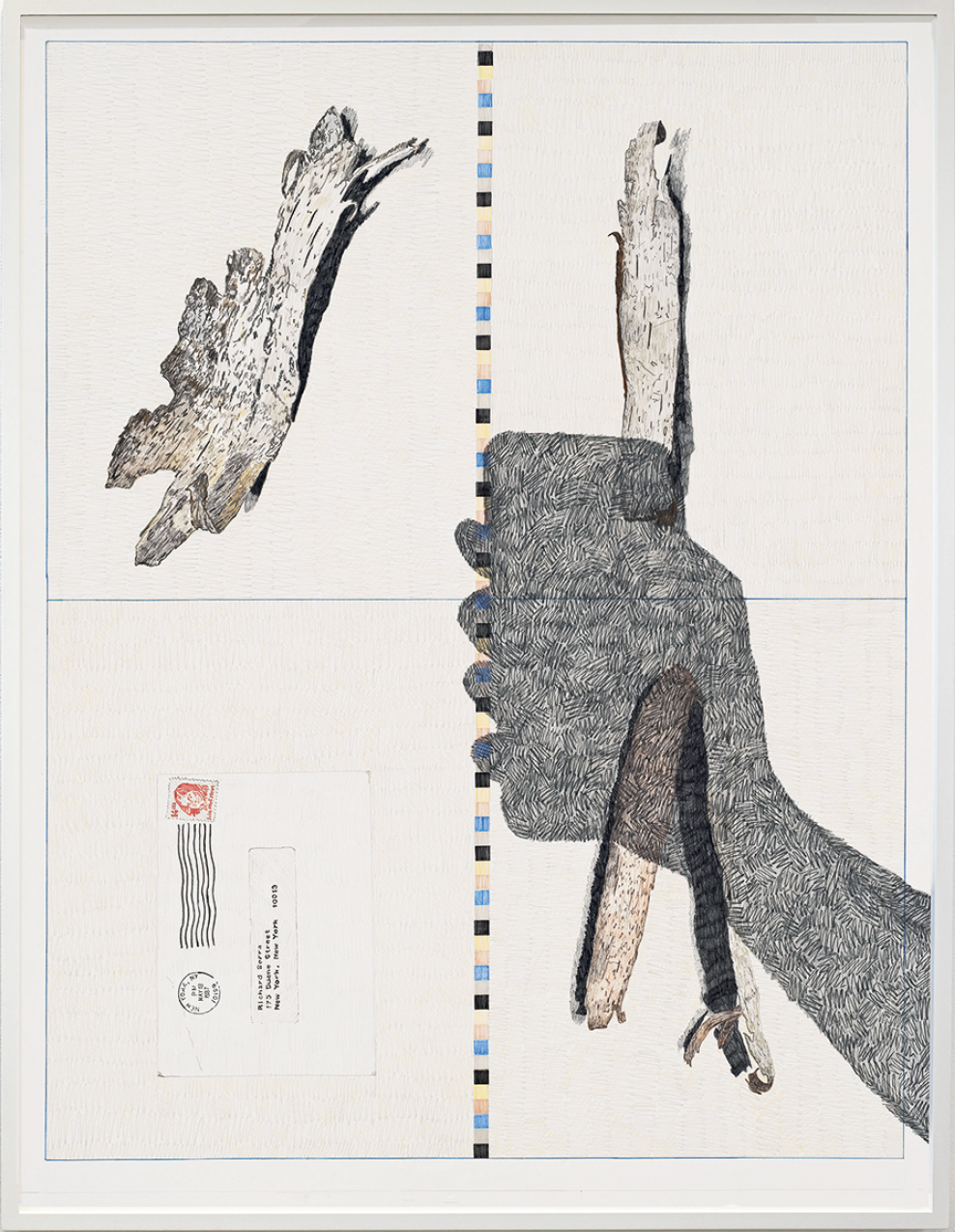

The first of four drawings in the show, #170, Field Publications, all 2022–23, is a key to the exhibition. It depicts pieces of tree bark, an envelope addressed to Serra and the shadow of a hand holding a cellphone. The composition is bisected horizontally by a thin rule and vertically by a colour bar, like those found on a four-page signature of a book prior to publication. The bark (along with rocks, feathers and other natural detritus) was collected by Sullivan during perambulations to and from Shift, and the cellphone, used to photograph the site, is his; both represent modes of documentation. The envelope comes from a bundle of exhibition invitations sent to Serra that Sullivan acquired from a dealer. This commonplace item is simply addressed to Serra. However, its resale speaks to how accrued value—in this case, through ownership by a famous person— leads to redistribution. The implication here, perhaps, is that Serra’s affiliation with an otherwise unremarkable plot of land has similarly imbued it with a rarefied quality. Does this mean that bark or stones taken from the site possess a unique aura? The depiction of the envelope and the tree bark within the same drawing seems to suggest so, if in a tongue-in-cheek way.

Derek Sullivan, #168, Field Publications, 2022–23, coloured pencil on Rising Museum Board, 133 × 102 centimetres. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. Courtesy Susan Hobbs Gallery, Toronto.

Sullivan’s shadow reappears throughout the show. His self-portrayal is a visual bridge between the drawings and viewers, but it also suggests his, and by extension our own, imposition on landscapes. Sullivan was interested in determining how Shift’s locale was being used and how often by people, through documenting traces left behind, such as cycling tracks, discarded food and drink containers, or foot and paw prints. Rarely did Sullivan encounter someone else during his visits. Indeed, depending on the time of year and the weather, he could sometimes tell that several days had passed without any human presence or when farming work had started on the field.

This idea of our presence/absence within, and the impacts on, environments also informs six untitled sculptures, all 2024, that resemble precarious mid-20th-century modern-style chairs. The wood comes from trees on the artist’s property outside of Tamworth, a small community north of Belleville. Once a thriving mill and farming town, the area went into decline when much of the forest was cleared, which subsequently diminished soil quality. On Sullivan’s property an invasive species of beetle is ravaging the birch trees, wood from which the artist used to make the sculptures. On the ‘seat’ of each structure lies an arrangement of tools— a compass, whistle and crystal prism—useful for navigating landscapes (and for seeking rescue if lost).

Rotating languidly from the ceiling is Weathervane, 2008, produced during the Scotland residency. Like collecting pieces of tree bark or stones, taking photographs and writing notes, observing a weathervane is a means of tracking changes within an environment that are unending and often imperceptible. This notion of the constant mutability of spaces and how we affect them is at the crux of Sullivan’s engagements with the Shift and Tamworth sites. Even the removal of something as seemingly innocuous as a rock or tree signals a change. ❚

“Field Works” was exhibited at Susan Hobbs Gallery, Toronto, from April 18, 2024, to May 25, 2024.

Bill Clarke is a Toronto-based writer and curator who has also contributed to ArtReview, ARTnews, Modern Painters and Canadian Art.