David Wityk

This is a curiously uncertain exhibition. It exudes a sense of mild disquietude, hovering tentatively and uncomfortably somewhere between documentation and art. The show comprises 13 montages created from photographs of abandoned industrial and commercial sites in Canada, the us and Eastern Europe. The images are disparate in size, scale, form and presentation. Eight are smaller pieces: prints over-matted behind glass, inconsistently framed in what appear to be retrievals from an art-shop waste bin. There are three larger works, board mounted and unframed, and two panoramic transparencies presented in crudely constructed light boxes. The quality of both prints and transparencies is adequate but not exceptional. The numerous speckles of imprinted dust evidence a failure to clean the original photographic material prior to scanning or printing. One could be forgiven, then, for thinking that there’s little here to engage the mind or, indeed, that is deserving of attention at all. That, though, would be a mistake for, wittingly or not (and I’m disposed more to the former), on a number of levels—historical, cultural and aesthetic—Wityk’s work offers a great deal to think about.

The pieces shown here are a small selection from an extended body of work that has engaged Wityk’s attention for a number of years. Superficially, they could be deemed to fall within the realm of what has come to be called post-industrial landscape or, in some circles, industrial archaeology. As such, they can be seen as a response to the social and political implications of the rapidly expanding rust belts of North America and post-communist, Eastern Europe. Of late, especially in the West, these ruined industrial plants and factories have been attracting increasing numbers of artist-photographers. While what results can be understood to be both an indicator and symbol of a deteriorating confidence and loss of global hegemony, in Wityk’s work especially, I suspect that something rather more complex is going on as well.

David Wityk, Akademie Medizine Centrum – Zabrze, Poland, 2009, photomontage, C-print, 40 x 96”. Courtesy Golden City Fine Art, Winnipeg.

Every civilization creates its monuments. Every monument is a ruin in waiting.

A fundamental characteristic of ruins is their capacity for simultaneous stimulation of both memory and imagination. History bears this out, at least in the West where awakened interest in ruins has seemed always to preface great shifts in humanity’s understanding of itself and its place in the universe. Dante and Petrarch, both Renaissance precursors, were drawn to the ruined grandeur of Rome. Their contemporary Boccaccio described the ancient Roman resort of Baia as old walls for modern spirits. More than a century later, his spiritual descendant Raphael, in a letter, called for the protection of the ruins of imperial Rome as a memory that served to inspire.

The phrase that comes most readily to mind when I look at Wityk’s pieces is “tender cruelty,” Lincoln Kirstein’s wonderfully concise characterization of the photographs of Walker Evans. Interestingly, these are also the words used in 2003 by London’s Tate Modern as the title of its first major photography exhibition, “cruel + tender: the real in the twentieth-century photograph.” The show featured the usual suspects, among them, August Sander, Walker Evans, Robert Frank, Stephen Shore, and Bernd and Hilla Becher, together with their acolytes, Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff and Thomas Struth. It was an unabashed celebration of the documentary tradition, at least as practised in Europe and North America. Ironically, given photography’s inherently postmodern nature, it was an equally unabashed celebration of the so-called “straight” photograph so valued by Modernism. I mention this because I think that whereas Wityk’s contemporary pursuers of industrial detritus, John Davies in England, for example, the Austrian Christoph Lingg or, closer to home, Québecois Jogues Rivard, could have fitted quite comfortably into the Tate exhibition. Wityk, despite what I perceive to be his closer affinity to Evans, could not. The difficulty would be his approach, which is decidedly unrealistic; not for Wityk a singular, selective view but rather a digitally assisted imbrication of dozens, not one moment but many, layered and stitched together in a Hockneyesque patchwork. Bernd and Hilla Becher, with their persistently wilful, if illusory, neutrality these are not.

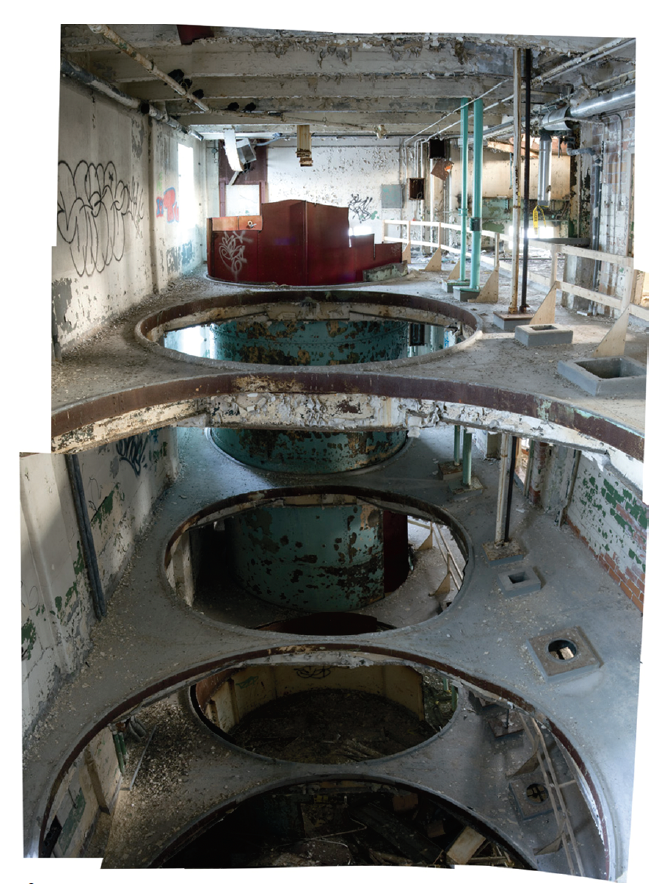

David Wityk, Okeefe Brewery Three Level Tank #3 – Montreal, 2009, photomontage, C-print, 48 x 30”. Courtesy Golden City Fine Art, Winnipeg.

On an aesthetic level, then, it is this oddly schizophrenic character, the distanced documentary impulse fine-filtered through a gauze of artistic ambition, that I find to be the most immediately compelling aspect of Wityk’s work. Since photography, or perhaps more accurately, photographs stormed onto the art scene in a serious way some 40 or 50 years ago, the art and every other world’s steadily growing embracement of celebrity culture has been making it evermore essential that artists seeking success establish a form of identifiable authorship, a style or visual rhetoric that clearly and unambiguously says me, not them. This is a huge challenge and especially so when working with photography, an inherently transparent medium that, when rigorously conformed to its original purpose, reveals to a viewer only the frame and the framed. The photograph itself—that is, photograph-as-object—becomes all but invisible, which, inevitably, makes the photographer all but invisible too. This may be fine for journalists but is utterly unacceptable for artists, whose success depends pretty much completely on being noticed, an imperative too often resulting in work in which these “notice-me” strategies are more interesting than the work itself.

Not that I find this with Wityk; there’s more integrity to his work than that, and although in one or two images he does skirt perilously close to the edge, he saves himself by not adhering too rigidly or consistently to any one strategy, the most obvious of which is subject choice. Analogue artists have long recognized that the illusion of surface produced by photographing the rusty, ruined and wrecked automatically privileges the reference over the referent. This Wityk uses to good effect, supplementing it through discrete employment of a digital stitch program to modulate the intersections of his montage components. Not only does this add an apparently physical dimension to the image surface, it sets up a quivering tension that succeeds admirably in acknowledging both the revelatory and constructed nature of the composite. And finally, Wityk eschews cropping, thereby drawing attention to the rectilinearity of the encompassing frame by counterpointing it with the uncropped, saw-tooth irregularity of the outer edge of the work it contains.

I suggested earlier that this show and the extensive body of work from which it is drawn locates somewhere between documentation and art. More significantly and in a variety of ways, in an uncertain age it sits upon the crest of that wave that is the poise-point between past and future, between memory and imagination. Two hundred and fifty years ago, as the belch of Watt’s steam engine heralded a revolution, the demise of which today so occupies Wityk, the French scholar Diderot assigned value to ruins not for their capacity to generate visions of a lost past but rather because in contemplation of such crumbling remembrances might be conceived the means to countering its repetition. ❚

“Forgotten Places: post-industrial landscapes” was exhibited at Golden City Fine Art in Winnipeg from May 7 to June 7, 2010.

Richard Holden is a photographer who lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba.