David Umholtz

“Recent Work”, Brian Melnychenko Gallery, April 1983

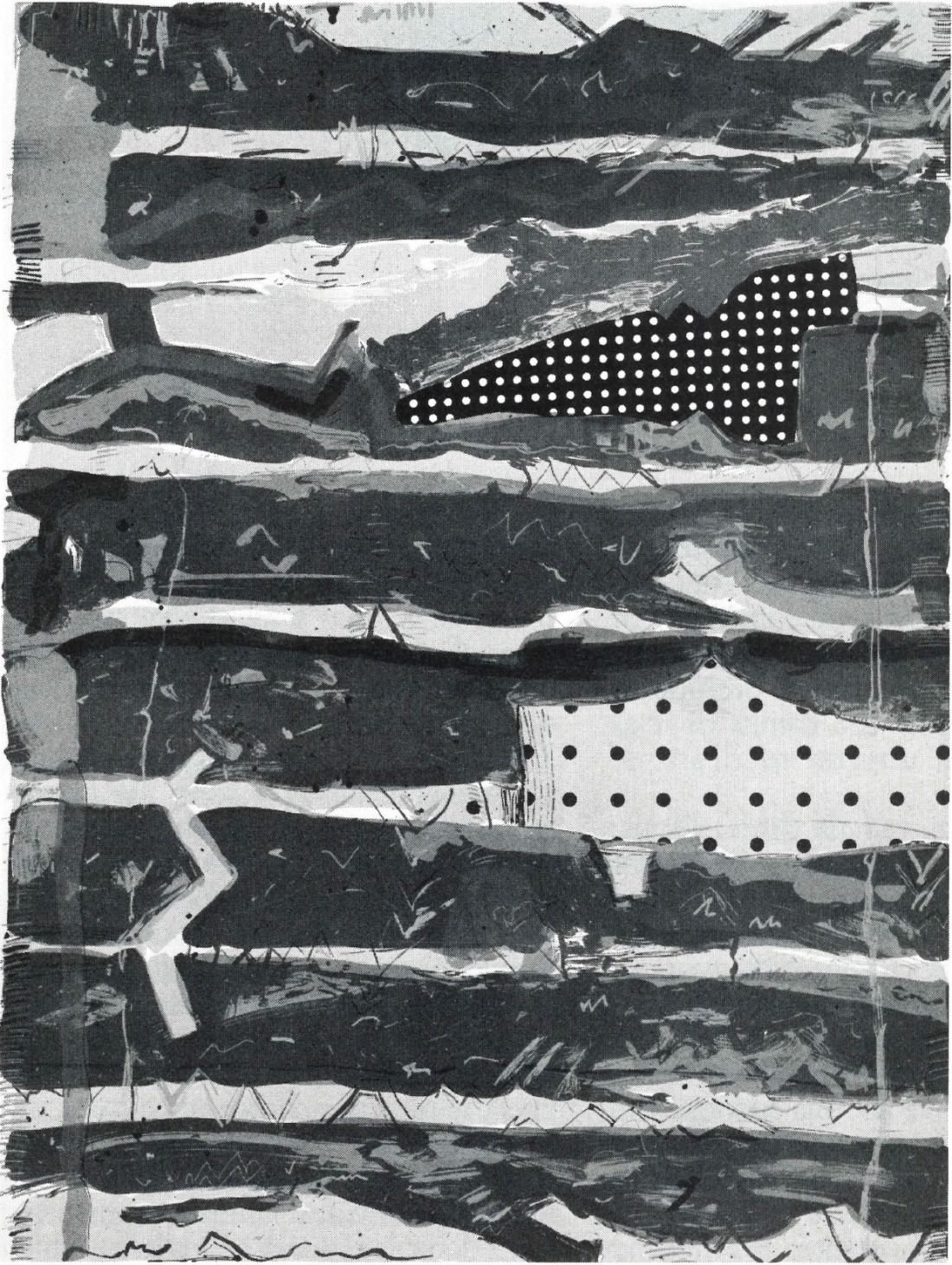

David Umholtz’s works exude bonhommie—exuberance. While the predominant colours in his paintings are sombre umbers and siennas, clear accents of blue, red and yellow effect a striking radiance by contrast. Sometimes, collage is introduced into the paintings, adding a jazzy touch and a textural change of pace. Umholtz’s earlier work struck me as being overly abstract and predictable, but this show is all freshness and spontaneity, and displays unflagging inventiveness. Apart from formal considerations, I think much of this effect comes from the introduction of recognizable subject matter. All the images are derived from an outer stimulus and establish that interesting tension between facture and representation that purely non-representational painting so signally lacks. There is landscape as in Sointula, Lubec Narrows and Beach at Kimono, quasi-symbolic themes like Three Mile Island or humorous whimsey like Cardboard Paris and Old School Tie. It is hard to say which predominates, the abstract or the pictorial, and it is in this very ambiguity that much of the charm of these paintings resides. It is a variation on the Bonnard type of painting in which the figure is hardly distinguishable from the surroundings, a “now you see her, now you don’t” situation, or one of those illusionist sleights where “now it’s a face, now it’s a vase.” I think the exploitation of this kind of ambiguity is an important element in art.

I don’t claim Umholtz is always successful. I think some of his works are stronger than others, but he has found a good approach, or rather an adventurous path, involving the major aesthetic dilemma of modern art.

NORTHERN HARBOUR, David Umholtz, 1983.

Such an approach involves no pat answers, of course, but instead, great risks, as does all true art. Cézanne’s formulaic apothegms are countered in his execution: not contradicted but countered. The geometric framework is overlaid with the rash gestures of involvement. In Umholtz, the prefigured armature is the precondition for freedom of execution. The subject in Three Mile Island or Blue Lake imposes a visual framework that sets the mood and tonality.

Umholtz, then, is no pettifogging formalist. He takes big risks. He splashes paint around. But the final result gives that sense of abandon under control that informs good art, as it does successful athletics. The effect is bold and unexpected. His colour is individual and sure. He sets off, as I have already remarked, vivid tones by sombre darks, greys, browns. In Sointula (acrylic and collage), he does it with pink and green against a murky raw sienna dashed with clear yellow.

I thought that Sointula (both the painting and the large woodcut), Beach at Kimono, Lubec Narrows and Old School Tie were the most successful works in this show. They display a clarity and firmness of image, a well established relationship between subject matter and facture not always evident to the same degree in some of the other works. However, it is hard to be choosey here. A piece like Augusta Northern Lights has an appealing boldness and a charge, but for me lacks the balance and sense of decorum of those I liked best. It is too ‘jumpy.’

I have not said much about the prints, two or three lithos and a few woodcuts, despite the fact that Umholtz is primarily known as a printmaker. Suffice it to say that the prints reflect the kind of sensibility and expertise which I have commented on in the paintings. Nevertheless, from now on it will be primarily as a painter that I will think of Umholtz. One associates colour first with painting and in this domain, this artist can hold his own with anybody. ■

Arthur Adamson is the visual arts editor of Arts Manitoba.