David K Ross

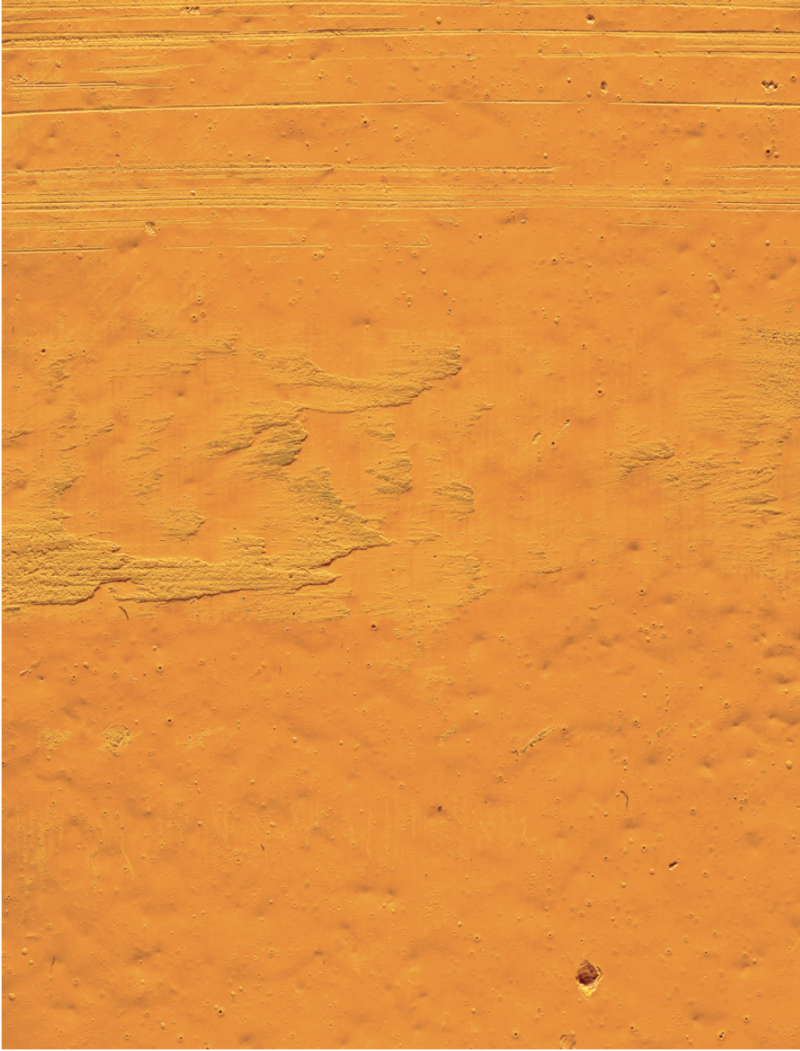

Colourful flat rectangles hanging on art museum walls are usually paintings. In the exhibition “Attaché” at the Musée d’art contemporain in Montreal, David Ross presents eight such colourful rectangles, yet their presence is enigmatic. The process of their production is hidden, as if they have arrived here all at once by magic. Close attention to these surfaces reveals what appears to be the texture of wood panels without their being actual wood but, instead, some kind of plastified image. Approximately a metre by a metre and a half, and six centimetres thick, these objects are titled with initials such as mbac/ngc or mnbaq, which some might recognize as the logos of various public museums. Each is basically a single colour, leaving a strong reference to the monochrome painting of the ’60s. On the other hand, a close look at the surface fails to detect brushwork or handcrafting at all. The resulting ambiguity of medium and referent is amplified by uncertainty as to the size of surface incident: while the literal surface of these objects is more or less smooth, there is a pictorial dimension in which depicted surface details flicker between the minute and the immense. This leaves us with a strong sense of that uncanniness that is part of today’s lexicon of photography. There is, however, no shortage of detail on these surfaces; in fact so much detail is available that it outran the capacity of my sight to take it in. The camera can capture more than the eye can see, processing and compressing a world into a format or a program. And so we have this experience of a tremendous excess, a surfeit of colour, surface and detail, a demonstration of immense technological power that has resulted in an encounter with visuality so emphatic with its “realism” that it is nearly impossible to see.

In fact these “paintings” are reproductions, something like the mass-produced items Duchamp selected for designation as art, a logic of the readymade Rosalind Krauss has applied to photography. There is a sense in which such “magic” is familiar: these “units” on the wall exist thanks to it—that is, to some process of technical reproduction. This sense is further enhanced as we consider the implication of reproducible paintings, of paintings without aura, something along the lines of Allan McCollum’s cast plaster “Surrogate Paintings” of the early ’80s.

Installation view of “David K Ross: Attaché” at Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, 2010. Photograph: Richard-Max Tremblay.

Or, could we go in the other direction to say that this is a post-anthropomorphic form of painting—that is, abstract photography? Consider Frank Stella’s shaped paintings in which shape can be said to equal form. Writing on Stella, Michael Fried divides space into “literal space” (bodily) against “pictorial space” (purely optical), and describes Stella’s canvas in the way it continues from the surface of the paintings around the stretcher bars. For Fried, Stella’s procedure maintains a consistency of spatial configuration in this wrap where, in the words of Stella’s famous dictum, “what you see is what you see.” In Ross’s treatment of the canvas surface, it wraps around the stretcher but with a different outcome: the literality of the canvas and stretcher support and the virtuality of the photographic surface no longer co-relate. In Ross’s work, a photograph of a flat surface is turned 90-degrees at the edge of a rectangle, thereby continuing that frontal surface onto a new plane. As a result, surface and depth, image and appearance contradict each other. What we perceive as a frontal virtual space becomes conflicted when it continues around the side of the stretcher bars. According to the logic photography sets out, we should be seeing a cross-section of a slab, but we don’t; what we see is an image wrapped around some kind of package.

What happens when a device such as Ross’s magnifying close-up camera lens and commercial production technique is incorporated into the mix? Strangely, what initially seemed so “visual” arrives by its own path to a point where that dimension is deemed inadequate, or even irrelevant, as a perspective from which the work can be considered. Without the anthropomorphic perspective, we are left to consider the work in its existence as a disembodied system. That is, there is a systemic correlation between the museum and photography that intersects in what was once understood as “memory,” especially in its common sense definition as “storage place.” This memory-storage place is now what we call “technics.” This leaves us in a curious situation: we are looking at many coloured rectangles hanging on walls just as this exhibition is showing how irrelevant is the perspective of aesthetics to understanding the thing we are doing.

David K Ross, MBAM, 2010 latex print on canvas, 223.5 x 170.2 cm. Courtesy Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

Included in the exhibition is a video projection that takes as its subject the function of the museum as a system for storage. We see museum shipping crates being walled away in a room, the very room in fact that is on the other side of the wall on which the video is projected. The projection fills the wall top to bottom, left to right. This video, in documenting the process, is of course itself another storage activity, recording and containing the “memory” of this process.

The museum, being a modern entity, functions according to a linear historical time, and thus clings to the model of an “authentic journey,” and this leaves it sadly “out of touch” with it’s own mode of operation. In the current context of electronic time, the here and the now relate in terms of displacement and deferral, and the museum, to be true to it’s function of preservation, is condemned to bring us to the scene “too late,” in the mode of “after.” Does this post-historical (technological) condition lead us to a definition in which what memory once meant is now forgotten? We might ask if it is still memory if it no longer remembers itself but has come to be literally what common sense has taken it to be, a place of storage.

This confluence of photography—that is, technical reproducibility—with the museum is the context within which David Ross locates his exhibition. In this case, the debate indicated by this question of surface and limit-edge is not that of painting vs. sculpture but the larger one concerning the contemporary status of memory in the time of electronic abstraction. Even more, there is posed in an exhibition foregrounding technological power, as this one does, the question regarding the status of anthropomorphism as anything intrinsic to art: in other words, does art need human beings? ❚

“David K Ross: Attaché” was exhibited at the Musée d’art contemporain in Montreal from May 21 to September 6, 2010.

Stephen Horne is an artist and writer based in Montreal.