David B. Milne

I may as well admit, straightaway, that although I have gone carefully through the Art Gallery of Ontario’s hefty, book-sized catalogue of David Milne: Watercolours, I cannot locate the source of the irritating title of the exhibition it accompanies: “David Milne Watercolours: Painting Toward the Light.”

Well, I find it irritating, anyhow. I suppose “toward the light” means something like “towards a greater and greater transparency of understanding generated from within the numinousness of light’s veiling down upon nature.” The phrase may be, in fact, Milne’s (though I couldn’t find it). As a trope, though it smacks of that sentimental, crowd-pleasing curatorial/PR touch, it is consistent with the kind of transcendentally soaked language Milne enjoyed from his reading of writers like Emerson and Thoreau (such as his statement about the landscape’s bringing him “face to face with infinity where anything might be and anything might happen”). This was found in AGO curator Katharine Lochnan’s press-kit essay. Be that as it may, the exhibition is more real, and thus more enjoyable, than its title.

It’s a big survey. There are 79 works in it (along with Milne-relevant artefacts and, rather oddly, a “reconstructed corner of Milne’s last cabin on Baptiste Lake, Ontario, that reflects his preference for [sic] simple lifestyle close to nature”), culled from the holdings of the AGO, the British Museum (which, along with New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, had mounted the exhibition last year), the Museum of Modern Art, the University of Toronto, the Art Gallery of York University, the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, the National Gallery of Canada, the Art Gallery of Windsor, Museum London, the Art Gallery of Hamilton, the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, the Milne family, and from private collectors.

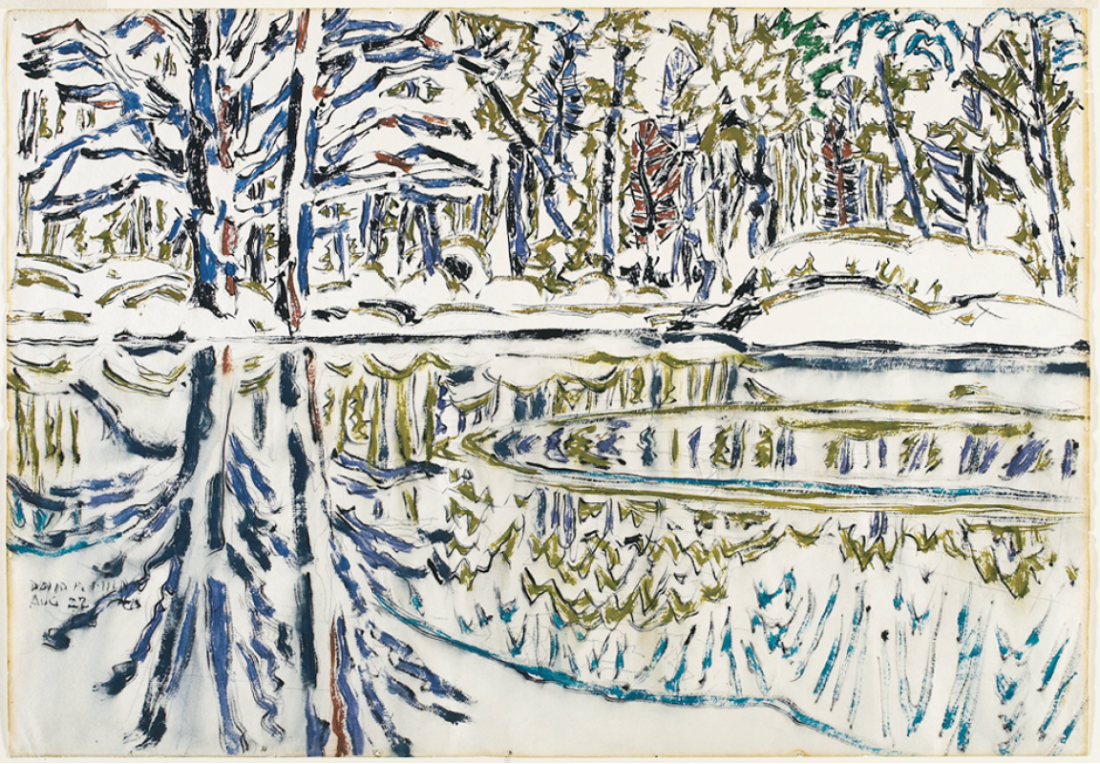

David Milne, Reflections, Bishop’s Pond, August 22, 1920, watercolour over graphite on wove paper, 38.4 x 56.1 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario. Photos courtesy AGO.

Milne (1882–1953) was a really quite radical painter—or, at least, he became so. In the early days, from the time he left his native Bruce Peninsula in northern Ontario, journeying to New York in 1903 to become an illustrator and to study at the Art Students League, until he moved to Boston Corners in upstate New York in 1916, he painted well enough in that jostling, shimmery, richly patterned, light-dappled, American Impressionist style reminiscent of painters like Maurice Prendergast, William Merritt Chase and Childe Hassam (though he was never to become as adventurous as Joseph Stella, John Marin or Marsden Hartley, all of whom were also more or less his contemporaries). It is important to remember that Milne was represented in the infamous Armory Show of 1913.

He strikes us now as having always been a more modern painter than the members of the Group of Seven were (they were also his contemporaries), probably by virtue of his increasing fondness for uninflected space in his pictures (as opposed to their fat-paint plenitude), the accelerating severity of his palette (he seemed increasingly at home with greens, blues, browns and blacks, as opposed to the Group’s long sojourn in “hot mush”), and that scratchy dry-brush technique of his by which he rasped out distances and the formal disposition of things in a way that still seems a compelling admixture of tentativeness—almost anxiety—and authority.

Milne’s watercolours were always finer than his oil paintings, and this exhibition is a more valorizing look at Milne than it would have been in full-tilt retrospective mode, with his oil paintings blaring away, sinking under their own weight. Carol Troyen, in her essay in the AGO catalogue titled “A Welcome and Refreshing Note, Milne and the New York Scene, 1903–13,” cites the artist as proclaiming that “[Watercolour] is so direct, so powerful, even brutal … it should be the painting medium because it is faster, and painting is the instantanous art.” I love the characterizing of watercolour as a “brutal” medium. Milne sounds here like a homespun futurist.

David Milne, Storm over the Islands III, November 10–20, 1951, watercolour over graphite on wove paper, 28.0 x 36.9 cm, Art Gallery of Windsor.

The Boston Corners pictures, 1913–17, are almost uniformly superb. There isn’t much in his work that’s better than—or as good as—his black and cream Reflected Forms, November 1, 1917, or his stunning, turbulent The Mountains (Catskills III), September 7, 1917. And the war paintings—or, rather, the immediately post-war paintings, since Milne didn’t get overseas until September of 1918. His sociological war paintings (impromptu concerts and soldiers writing home, etc.) are useful enough documents, but his bleak vistas of ruin and hopeless, endless elegy—such as his astonishingly reverberant Montreal Crater, Vimy Ridge, May 17, 1919 and his Loos from the Trenches on Hill 70, August 23, 1919—still make your blood run cold.

Then he gets back home to Boston Corners (and Lake Placid) and the great black paintings follow—postwar, all-passion-spent pictures if ever there have been some: now, the grounds grow black, and the picture is imposed as white. Or, contrariwise, the pictures are fully, haughtily creamy, with drags of dry black watercolour chewing at them like an infection (Reflections, Bishop’s Pond, August 23, 1920, or the violently resigned Dark Shore Reflected, Bishop’s Pond, c. October, 1920).

There isn’t much space left here to discuss the later paintings. Many of them are brilliant, especially the still lifes, some of them are ragged and goofy and, for Milne, hysterical (Goodbye to a Teacher III, 1938, and Resurrection III, 1943), while some of them are wet—among the wettest watercolours ever made (Bay Street at Night, November 4, 1941).

What happens at the end, however, is extraordinary. At the top of his form, say around 1919, Milne is poised like an acrobat on a tightrope of line and light. By 1951, two years before his death from cancer, he throws himself, procedurally speaking, into a strange arena of pure feeling, the matrices of which seem to have been water and weather. It is painting as exhalation and as withstanding. There are four last watercolours, as plangent as Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs, that are so dismaying they are both balm and cataclysm: the four Storm over the Islands paintings. In their appalling fullness of being, there’s almost nothing there. ■

“David Milne Watercolours: Painting Toward the Light” was exhibited at the British Museum, London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in 2005, and at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto from February 25 to May 21, 2006.

Gary Michael Dault is a critic, poet and painter who lives in Toronto.