David Altmejd

In his first major Canadian show outside Montreal, David Altmejd’s sprawling, fantastical sculptures occupied three rooms of the Gairloch Gardens gallery in Oakville, Ontario, giving a compact but evocative look at an extremely prolific young artist. Altmejd’s representations of decaying werewolves and other mythical monsters have brought him fame in New York City, London, Brussels and Istanbul, and now his work will appear in the Canadian pavilion at the Venice Biennale, in June 2007.

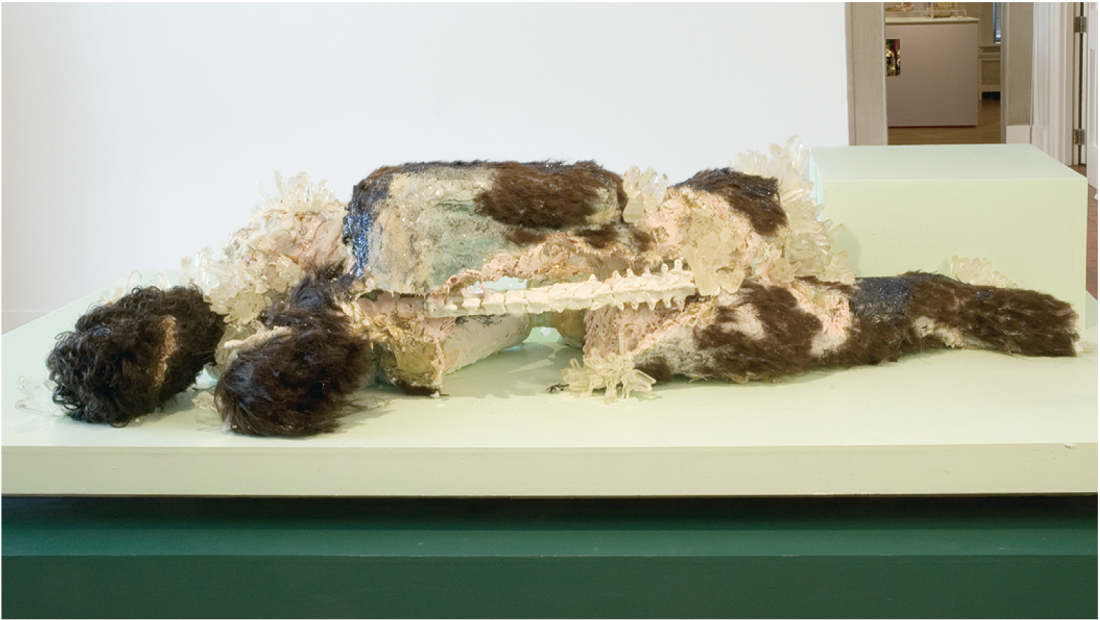

Always interested in transformational energies, Altmejd began to fix his attention on werewolves several years ago. His guiding image, he has said, is that of a man/wolf killed in the process of metamorphosis, its brutal death releasing tremendous power. Decomposing, the creature sprouts crystals, mirrors and jewellery, turning death into sparkling surfaces bedecked with craft-shop glitter and gold chains. In Altmejd’s versions of death and transfiguration, there is no messy rot, only the clean gleam of inorganic shards. The sculptured remains are admittedly hideous, with their snarling fangs and matted (polyester) hair. But they are no more terrifying than a B-level horror movie and all these depictions of glamorous and exuberant corrosion are displayed within acrylic vitrines or on painted platforms that could come straight from Ikea. Fetishistic flourishes include fake flowers, sex toys and sadomasochistic gear.

David Altmejd, The Lovers, 2004, Plexiglas, mirrors, lighting system, plaster, foam, resin, synthetic hair, jewellery, wire, chain glitter. All photographs: Cheryl O’Brien. Courtesy Oakville Galleries, Oakville, Ontario.

The Oakville show offered three works, dating from 2000 to 2006. In the strongest piece, The Lovers, 2004, two werewolves are enfolded into death, coupling as they died, and even their fangs and fearsome claws don’t lessen the sense of tenderness and sorrow of their passage. The small golden chains threaded through their plaster bones represent, Altmejd says, the nervous energy connecting them in death, as in life. There’s an inherent sexual charge in our understanding of the werewolf—or of any man-to-creature shape shifter—stemming, it’s presumed, from our fear and fascination with the power and shameless eroticism of animals. The Lovers presents us with a romantic notion of death as transformation, while giving the monsters an inalienable dignity. What weakens the piece is Altmejd’s characteristic use of boutique-style display. His use of reflective panels, plastic cases with cut-out windows and sprinkles of fake flowers, is a deliberate part of his process. Yet, in The Lovers, Altmejd’s insouciant presentation of tragedy undermines its majesty.

The Hunter, 2006, is the newest sculpture in the Oakville exhibition and continues Altmejd’s examination of decay and rebirth, although, in this case, his sexy beast is a gigantic head. Lying on one side, empty-eyed, its mouth parted in a toothless grin, the creature is slowly returning to the earth. This transformation is hinted at through taxidermied squirrels capering about the head, by artificial flowers and other signs of “nature.” A mirrored staircase runs along one side of the creature; in order to see inside its hollow cavity, the viewer has to stoop and peer through various window-like openings. Appearing within are a black “gimp mask” and leather bindings, both used in S&M sex play. Other cavities within the structure hold crudely handmade phalluses.

These campy references seem to have no particular purpose, other than to bump up the piece’s ambiguous sexual power. But then, it is part of Altmejd’s method to let his work go wherever it wants, a fact he articulated in an interview with C magazine in 2004. “I want my works to have an intelligence of their own, not just be slave to my meaning,” he said. It is not Altmejd’s laissez-faire approach to creating that is unusual, but rather his confident and self-referential optimism. His influences, he has said, include Sol LeWitt, Lucas Samaras, Kiki Smith, Matthew Barney and Louise Bourgeois, but now he adds that he considers his work sufficiently dense that it can carry its own weight.

David Altmejd, The Lovers, detail.

Giants are Altmejd’s latest passion; his Venice exhibition will incorporate an enormous foam sculpture of a chopped-up behemoth—along with werewolves and the sculptured birds that he has used in other work. His 2006 Giant, a huge foam and resin figure 290 centimetres tall, is a capering yet crumbling figure that resembles a Matthew Barney figure dipped in wax. It was recently shown in London, and, judging from photographs, the piece may represent a new and tougher vision, at the same time jaunty and sinister.

Altmejd’s fascination with mirrors and labyrinths—inspired, he says, by Jorge Luis Borges—was most apparent in the oldest of the sculptures shown in Oakville. Loup Garou II, 2000, is an architectural structure similar to a department store’s display of goods such as cosmetics. Within its base is a small window through which can be seen a single werewolf head, reproduced, through a cunning placement of mirrors, in a kaleidoscopic pattern. The upper cases contain plastic flowers and a half-rotted, crystallizing werewolf haunch. It’s decoratively baroque, fussy and lacking rigor. Altmejd engages his viewers to peek through labyrinths and cutouts, distracting them with their own mirrored images, but the mystification process is also offputting. He said, at the opening of the Oakville show, that he likes the “disco-ball” effect of the kaleidoscope and that the kitschy flowers are there just because it’s not the sort of thing a modern artist should do. This naughty-boy attitude could wear thin, especially when it reduces the considerable impact of his imagery.

Because Almejd is so productive, these three sculptures gave only a hint, although a strong one, of his methods and evolution. He is as well known for his complicated architectural structures as for the dying lycanthropes and other creatures imprisoned within them. His work is most compelling when he maintains a tension between terrible beauty and its coolly detailed enclosure. ■

“David Altmejd” was exhibited at Oakville Galleries in Gairloch Gardens from January 27 to March 25, 2007.

Kate Regan is a Toronto-based arts writer.