Dave Heath

“Multitude, Solitude,” curated by Keith Davis, is the first comprehensive survey of Dave Heath’s deeply personal photographic work. The 180 works in the exhibition focus on his black and white photography from 1949 to 1969—the first 20 years of his career. The exhibition fills a gaping hole in the survey of American photography and serves to define the aesthetic and emotional potency of Heath’s work.

Dave Heath’s personal narrative and work are not as well known as that of his contemporaries. Inspired by great photographers like Edward Weston, Robert Frank and W Eugene Smith, Heath’s work is held in numerous collections such as the Museum of Modern Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, George Eastman House and the National Gallery of Canada.

Heath was born in Philadelphia, abandoned by his parents and left an orphan when he was a small boy. He was raised in an orphanage, served in the Korean War as a gunner and appeared almost overnight as a photographer with a sharp eye, impeccable framing and unstoppable dodge-and-burn darkroom skills. As a young photographer he was the recipient of a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship and his photographs were published in periodicals such as Modern Photography, Camera 35 and Popular Photography. Despite his success in the photographic art world, once he moved to Canada and began teaching at Ryerson University, he was no longer producing the same iconic style of black and white photography.

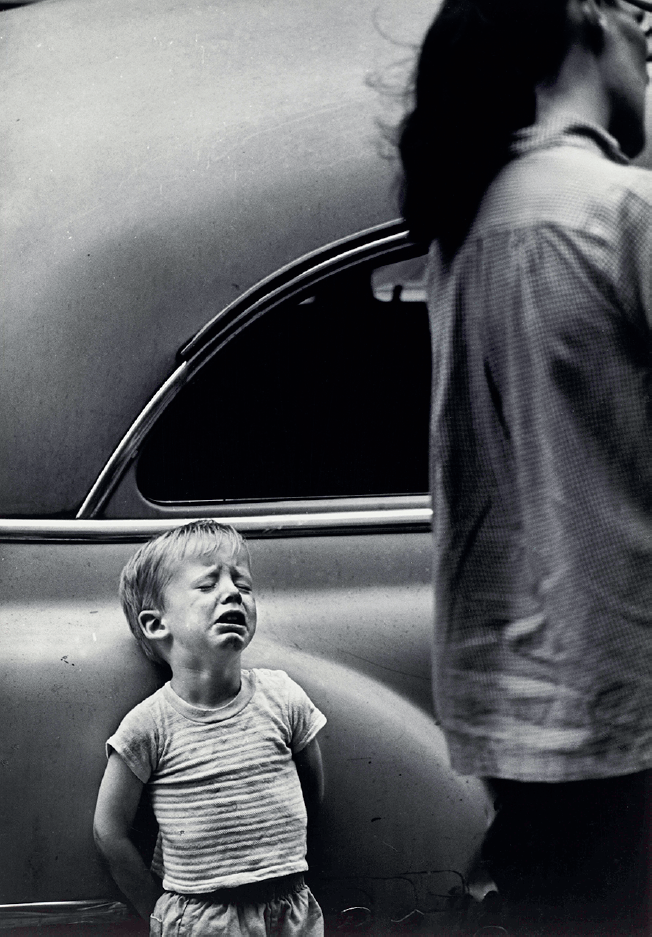

Dave Heath, Rochester, New York, 1958, gelatin silver print, 16.5 x 24.7 centimetres. The Nelson- Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of Hallmark Cards, Inc., 2005.27.1428. © Howard Greenberg Gallery and Stephen Bulger Gallery. Images courtesy the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

Heath was never a household name, but he became an influential figure in photography. James Borcoman, curator emeritus at the National Gallery, has said that Heath’s 1965 book, A Dialogue with Solitude, was “the most important book produced by any photographer in the 1960s.” A Dialogue with Solitude is the centrepiece of the Heath exhibition. The maquette of the book is framed and displayed like a shrine to the medium and to the man.

Heath was inspired by Life magazine and the pages of black and white photography from the photo essays that dominated the pages. The photo essay reigned supreme as a method of storytelling in the 1940s to the 1970s, and Life magazine had a formula to captivate audiences. The stories and method were perfectly illustrated by W Eugene Smith, Edward Weston and the legions of American photographers working on assignment for the magazine. Photographers would tackle stories that were of wide-ranging human interest, working with a framework of illustrative storytelling. The story would move from wide-angle establishing shots to medium-range shots and then tightly framed close-ups and portraits that were key factors in the magazine’s signature style.

A Dialogue with Solitude was a stylistic homage to the photo essay. Heath’s passion for photographic expression and the characteristic feelings of the Beat Generation—the social and literary movement originating in the 1950s and centred in the bohemian artist communities of New York and the West Coast— had a clear impact on Heath’s work. Living in Philadelphia at the time, he adhered to the “beatniks’” expressions of alienation from conventional society. Though not necessarily indifferent to social problems, Heath advocated personal release, purification and illumination through a heightened sensory awareness in art, and seemed to find the joylessness and purposelessness of modern society sufficient justification for both withdrawal and protest.

He also sought to incorporate poetry into his writing, and deliberately selected poems and quotations to support the “disenchantment, strife and anxiety [that] enshroud our times in stygian darkness” (preface). Citing the same anguish of having been born into an unsettled society that tormented great men like Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Shakespeare, Goya, van Gogh and Kafka, Heath includes himself amongst these tormented creatives. All that he would convey in his work was backed by the feeling that pleasures were less than pains and joy was fleeting but despair ominous. His own Dialogue with Solitude was to reveal and catalogue the dark and haunting sides of the human condition.

Throughout the main exhibition are photographs that Heath took around the United States and in Korea. Whether of individuals or situations, they are almost invariably tightly cropped, as if the artist had tightened his focus on the subject to better understand the people, the situations, the world he was inhabiting.

The exhibition opens with portraits of American soldiers in Korea. His portraits of young soldiers, expressionless and held within the frame, are immediately beautiful and carefully crafted to be timeless; the images could be of any war, of any time. Heath photographed the idleness and stillness of war in a way no other photographer had yet to accomplish. He was inspired by Robert Frank and found many ways to capture the human condition on the streets of his hometown of Philadelphia. He produced intimate but desperate moments of loneliness—a man passed out on a bus or a couple sitting on a park bench staring into space. These moments seem abstract and somewhat disconnected.

Heath stopped printing black and white photography in 1969. At that time he began to focus on audiovisual slide shows. Included in the exhibition is a digital version of his first slide show entitled Beyond the Gates of Eden, 1969. This period also marks Heath’s adoption of the Polaroid format. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s he took thousands of Polaroid photos and produced elaborate, mixed-media journals (some of the original journals were on view in the Canadian installation of the exhibition curated at the National Gallery by Andrea Kunard).

Dave Heath, New York City, 1962, gelatin silver print, 23.8 x 21.6 centimetres. The Nelson- Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of Hallmark Cards, Inc., 2011.67.32. © Howard Greenberg Gallery and Stephen Bulger Gallery.

In the early 2000s, working as a photography archivist at Library and Archives Canada, I was charged with processing the mixed-media journals of Dave Heath. Until this point, I knew only his vintage black and white work from A Dialogue with Solitude. This book, as many would agree, was one of the most substantial photographic books of the decade in which it was published. Heath’s journals are abundant. These works of art— inner thoughts, self-examination, Polaroid photographs and collage— are carefully glued and staged. Heath curated his own daily life through his obsessive and prolific creation. Seeing a few pages of the journals displayed alongside the exhibition of vintage prints allows the audience to think of Heath as a photographer who continued to create beyond the work covered in the main exhibition. This is helpful because he never stopped creating; he just changed completely the output from his early handmade books to the slide shows and Polaroids to copious numbers of journals. The themes dominant in the vintage black and white photographs are present throughout his journals and into the final phase of his production: digital photography and colour printing. His work, spanning his lifetime, exists without his voice framing it in any way other than as a dedication to the human condition replete with suffering and shadow. Some have said he was eternally lonely, and certainly in the pages of his journal he laments his career and his own significance. This exhibition allows for that wonderful significance to shine through. ❚

“Multitude, Solitude: The Photographs of Dave Heath,” a touring exhibition, was at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, from March 14 to September 2, 2019. The tour included the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth and the Nelson- Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City.

Joanne Stober is a curator and historian of photography currently working as the historian of War and Visual Culture at the Canadian War Museum.

To read the rest of Issue 152, order a single copy here.