Dana Claxton

The Vancouver Art Gallery’s (VAG ) s t e l l a r D a n a Claxton exhibition was, in many ways, a first. It was the first major survey in the acclaimed multimedia artist’s 30-year career and the first time many of her significant works have been exhibited in Vancouver, the city in which Claxton has been based since the mid-1980s. At the same time, the show consolidated our understanding of her dominant and recurring themes, including Indigenous history, culture, beauty and spirituality. While her art often alludes to the destructive legacy of colonialism, it also celebrates the contemporary resurgence of First Nations’ presence and identity. What emerged through this engrossing selection of Claxton’s photographs, videos, mixed-media installations, text works, banners and performances was the sense of an artist maturing into her creative prime, honing her voice and vision along with her forms and strategies and delivering works of ever greater power and conviction.

The show’s subtitle, “Fringing the Cube,” is a reference to the traditional fringed clothing of Claxton’s Hunkpapa Lakota (Sioux) ancestors and to the “white cube” model of the contemporary art gallery. It is an assertion of Indigenous claim to an institutional space—“white” signifying much more than the colour of the walls—and was made palpable by the presence of an exaggeratedly fringed deer-hide garment mounted in the show’s first gallery. Made by Claxton’s sister, Kim Soo Goodtrack, this garment had been worn by the artist in a performance at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2015. It exuded both beauty and drama, qualities that Claxton often employs, drawing viewers into her work while also challenging social assumptions, critiquing cultural stereotypes and asserting First Nations’ resilience and survival—what the Anishinaabe theorist and poet Gerald Vizenor has termed “survivance.”

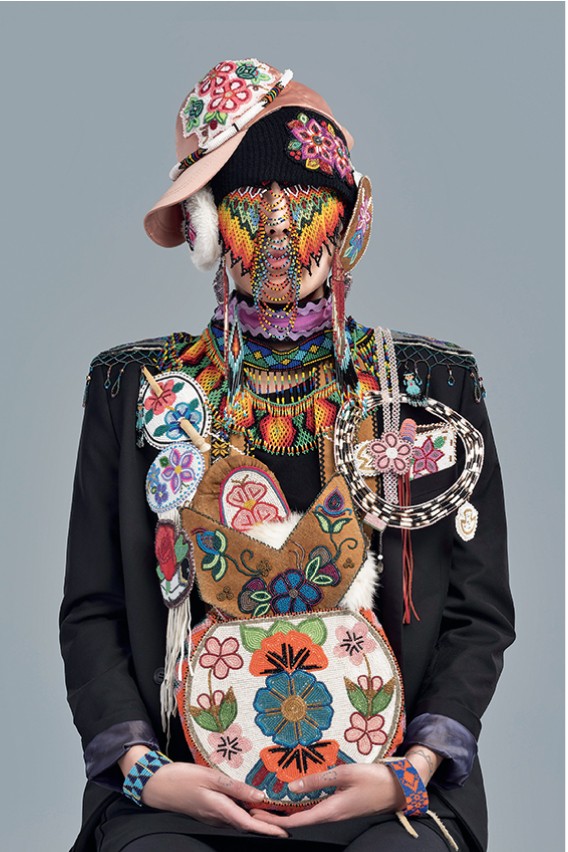

Dana Claxton, Headdress–Jeneen, 2018, LED firebox with transmounted chromogenic transparency. Collection of Cathy Zuo. All images courtesy the Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver.

A number of Claxton’s themes are entwined in Cultural Belongings, the large-scale, backlit, colour transparency installed at the exhibition’s entrance. (Claxton uses the term “firebox” instead of “light box” and “windbox” instead of wafting silk “banners” printed with text or photographic images. Such word play provokes us to reconsider the dominance of certain white male artists’ forms, and conventions in mainstream galleries, and also to recognize the power of language to shape cultural understanding.) My first encounter with this work, which was used by the VAG as the signature image for “Fringing the Cube” and as the cover image for its catalogue, was in 2016. At that time, it was part of a Simon Fraser University exhibition in which Claxton asked us to consider the ways in which Indigenous women have long been represented in museums and galleries—that is, as the anonymous makers of countless cultural belongings. Such objects, Claxton reminded us, have too frequently been displaced from their original contexts, stripped of their meanings and their “use value.”

The photo depicts a woman with long black hair dancing confidently forward against a flat, black ground. Wearing a short, sleeveless dress, high heels and a densely beaded veil, she holds a horse-head dance stick in front of her while pulling behind her, on a long deerskin robe, quilled, beaded, embroidered and woven objects, including belts, bags, drums, a bark basket and a parfleche. On first viewing, the image conveys an uncomfortable ambiguity. It forges a connection between the past and the present and makes a proud declaration of gender and heritage, but at the same time, the face-obscuring veil seems to be a critical reminder of the anonymity imposed upon the women who created these “cultural belongings.” Or at least that’s what I thought when I first looked at this work. Only later did it occur to me that the veil might be a refusal of the colonizing gaze of the viewer, shielding identity rather than erasing it.

Claxton has repeated the beaded veil motif in some half-dozen backlit transparencies, the most recent in the show being Headdress–Jeneen, a 2018 image of the acclaimed young performance artist Jeneen Frei Njootli. She is portrayed extravagantly draped in some 15 beaded objects from her own collection, including hats, bags, bracelets, necklaces, moccasins, barrettes and a small curtain of coloured beads that covers her eyes and cheeks. Here, the deflection of the viewer’s gaze is immediately understood, so that Frei Njootli is not the object of the portrait but the subject, collaborating with Claxton to maintain control of her image—an image of feminist, cultural and spiritual power. Claxton has spoken about the “transformative” nature of working with Indigenous women—friends and colleagues—in creating the “Headdress” series. She has also remarked on the unsettling impact on the viewer of covering the sitter’s eyes, which are, she said, “a place of spirit.”

With equal parts heart and mind, form and content, beauty and criticality, Claxton has taken on a succession of social, cultural and political concerns throughout her career. In the performance-based, mixed-media installation Buffalo Bone China, 1997, she deplores the US government’s extermination of the buffalo, a cruel policy designed to undermine the culture and destroy the livelihoods of the Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains. The exile of the Lakota people (including Claxton’s maternal greatgrandparents) from North Dakota and their prolonged encampment in southern Saskatchewan following the 1876 Battle of the Little Big Horn is spotlighted in the four-channel video Sitting Bull and the Moose Jaw Sioux, 2004. The surveillance and repression of the American Indian Movement is examined through large photographs of heavily redacted FBI documents in the 2010 “AIM” series. (With a certain degree of art historical irony, Claxton has pointed out that some of the redacted documents resemble Rothko paintings.) Stereotypical and popular culture notions of “the Indian,” especially as constructed within the context of “the Wild West,” are explored through the “Indian Candy” series. This body of work, which consists of appropriated photos and documents, copied, enlarged and tinted in paradoxically sweet colours, was produced in 2013.

As well, what curator Grant Arnold has described as “complex questions regarding history and the performance of identity” are evident in the large colour photographs of an Indigenous “family” in the Mustang Suite, 2008, and of a woman’s subtly shifting cultural identification in Onto the Red Road, 2016. Arnold also points out that Claxton’s emphatic use of the colour red—red clothing, shoes, accessories, furniture, bicycles, car—in these works alludes to both “Red Power” and the sacred nature of that colour in Lakota belief. Claxton’s background in theatre, television and fashion photography contributes a bright, crisp, highly directed aesthetic to her art. Her own performances, videos of which were shown on monitors throughout the show, also inform the dramatic presentation she coaxes from her models.

Cultural Belongings, 2016, LED firebox with transmounted chromogenic transparency. Collection of Rosalind and Amir Adnani.

The most recent works in Claxton’s show are wonderfully celebratory. Spanning large-scale photographs, a commanding firebox and an engaging “video flipbook,” they feature a group of fit young men drawn from Vancouver’s community of Indigenous ironworkers. Completely defying any of the cultural stereotypes that might be assigned to them, they daily undertake demanding, dangerous and well-paid labour in the construction industry. NDN Ironworkers, 2018, depicts a line of eight young men, kitted out in their work gear, striding toward the camera and exuding what my fellow critic Beverly Cramp has identified as “pride, confidence and autonomy.”

Claxton, who is an accomplished Sundancer, returns repeatedly to the subject of Indigenous spirituality. Through photographs and videos evoking Lakota beliefs and ceremonialism, she creates art of inspiration and affirmation, a kind of formal and thematic counterpoint to criticism and admonishment. One of the most moving works in the show—the one that closed the circle of belief laid out at the VAG—was Rattle. A four-channel video that Claxton has described as “a visual prayer attempting to create infinity,” it was projected large-scale in a darkened gallery, inviting the viewer to sit and become fully immersed in its visual and aural rhythms. The soundtrack included peyote songs sung by Verdell Primeaux and Johnny Mike and ethereal electronic music composed by Claxton’s long-time collaborator, Russell Wallace. Abstracted passages of symbolic blue were succeeded by close-up shots of animal hide rattles being rhythmically shaken, the left-hand imagery mirroring the right. To watch and listen to this work was to give oneself up to the shifting forms and colours, the chant-like singing and the gentle, repetitive shushing of the rattles. The effect was both meditative and mesmerizing. I didn’t want to leave.

“Dana Claxton: Fringing the Cube” was exhibited at the Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver, from October 27, 2018, to February 3, 2019.

Robin Laurence is a Vancouver-based writer, curator and contributing editor to Border Crossings.