Damien Moppett

Working from home during a pandemic can be a challenge when it means looking at art from home (that is, virtually, online) and writing about it. There is no substitute for the experience of the real thing. Even so, this account of “Damian Moppett: Vignettes” at the Catriona Jeffries Gallery in Vancouver stems from a visit to the gallery’s website, whose virtual features made this possible, plus a Zoom interview with the artist and emails. The excellent site included an exhibition guide, a checklist, a gallery tour and installation shots that accompanied images of the paintings, as well as several large details. Absent the materiality of painting, virtual images and their proximity in virtual space brought ideas implicit in, or triggered by, these works into the foreground. And this artist’s practice has never been short of ideas.

“Damian Moppett: Vignettes” is the 51-year-old Vancouver artist’s first exhibition devoted to figurative painting and the first to contain images taken from the history of modernist photography. In his words, the dozen paintings here are “defiantly a new body of work coming out of a newish way of working.” Conceived of as an exhibition with a tight focus, the paintings have arrived following a two-year hiatus in which Moppett, disillusioned by the art world and the efficacy of art, mostly stopped making art. While his practice includes sculpture, drawing, photography and video, when he began again it was to paint. He painted en plein air, worked through some ideas in landscape and still life and then, in early 2020, started on the vignettes. This is his first exhibition that developed organically from scratch, he says. With it he takes a long-considered step towards making work that comments on social context and the times, as exemplified by Daumier, James Ensor and Otto Dix.

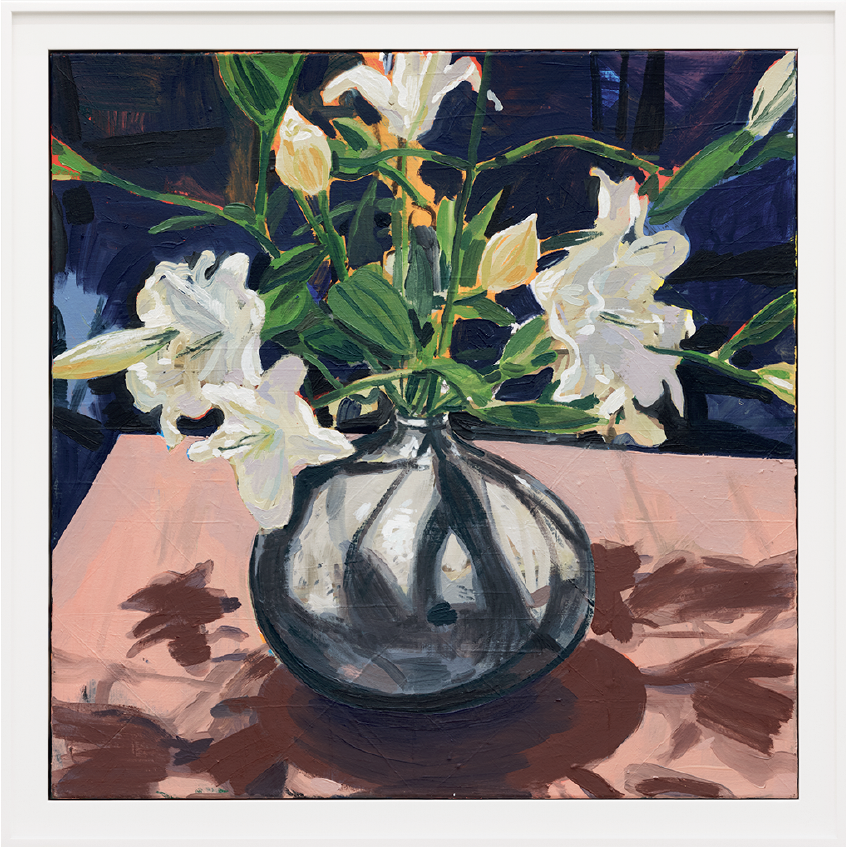

Damian Damien Moppett, Lilies (Pink), 2020, oil on canvas, 34 x 34 inches. Images courtesy Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver. Photo: Rachel Topham Photography.

Moppett made photographs as art in the 1990s and always works from photographs as part of his painting process. He enters the longstanding art-historical conversation between painting and photography with “Vignettes,” and complicates it. Three subjects common to both painting and photography—the figure, still life, swimmers—are in the image mix, but 1970s photographs by Lee Friedlander, in particular, offered contextual subject matter that Moppett was looking for. Among the 12 paintings in the show, five are based on photographs of people at parties, openings and a fashion shoot by Friedlander; two on solitary swimmers by André Kertész and Dorothea Lange; one on a 1917 advertising photograph by Edward Steichen; and three on Moppett’s own photos of stacked towels and two vases of lilies. Unifying the whole, Moppett’s idiosyncratic cartoonish painting style adds layers of allusion by bringing up a host of painters he looks at closely: Philip Guston; the British artist William Nicholson (1872–1949), who must have looked closely at Manet; van Gogh; Alex Katz; Fairfield Porter; Alice Neel; and always in the back of his mind, Maxwell Bates.

All of the paintings are based on photographs that in turn were all shot in black and white. As if to make the point, the gallery’s mailer for the show held, instead of the customary invitation card, three black and white photographic prints of source images for paintings. Transcribing a photograph into painter’s language, Moppett has added colour, surface texture and an array of different kinds of drawn lines, marks and broken strokes. A painter like Guston might be invoked by a colour (carmine-reddish pink), a detail (an eye in profile shaped like a wedge), an image (a blonde who recalls Guston’s paintings of his wife Musa) or a distinctive way of drawing (a hand with angled fingers outlined in pink). The hair and eye in Little Blonde Head, 2020, call up Guston in a painting based on Friedlander’s photograph Los Angeles, California, 1970. Moppett has altered the photo image with a tight crop on the blonde woman in the foreground talking to an avid man in the middle distance, with the closely present figures in the crowded background cloaked in dense shadow. A similar blonde woman in profile appears in the painting Hand and Head, 2020, again based on Friedlander.

_2020_Vignettes_CJ_2021_01_1100_1466_90.jpg)

Damian Moppett, Patron (White Dress), 2020, oil on canvas, 50 x 58 inches.

Each of the paintings based on a Friedlander has three clearly demarcated zones that compress pictorial space and push it forward to exert heavy pressure on the picture plane, which is considerably larger than that of the photographs. The viewer thrust into the midst of the action is positioned where Friedlander was when he took the photograph and where Moppett was when he addressed the canvas. In Hand and Head, foreground colours are blown out as if by the light of a flash. The enlarged source images, vivid colour palette and acute spatial compression raise the levels of intensity and immediacy in the paintings. Figures, some larger than life, become exaggerated comic characters. And if the feeling of a moment snatched out of time is held by the eager expression on a character’s face, Moppett compounds the notion of time embodied in painting with resonating allusions to other painters and photographers of other periods. Painting, even on one canvas, is a durational process, let alone in the four or five layers of older paintings that Moppett laid down first underneath these new works. Hints and bits of the old paintings appear on the fresh surfaces. Histories concealed and alluded to pile up. In addition to Nicholson, lilies bring up Katz and Robert Mapplethorpe, swimmers point also to Hockney and Edward Weston, exaggerated figures recall Weegee and Alice Neel.

The compressed intensity of the paintings is, for Moppett, the “Vignettes’” step towards social commentary. The definition of a literary vignette as a vivid description of a moment in time that suggests a larger narrative suits these paintings well, as does its application in film and television as a brief but powerful scene. When I looked at the installation as a whole, the linked vignettes suggested if not a narrative then an allegory. Alternating with the figure paintings, Moppett’s still lifes brought personal moments of quiet domestic life into the gallery scene, with a nod in the stack of towels to sculptors Liz Magor and Andreas Slominski, who have been important to his practice. Two paintings, whose figures echo one another, held key positions. Man and Woman in Mirror, 2020, based on Steichen’s bizarre photograph of two figures posed in front of a mirror-covered pedestal topped by a vase of lilies and positioned by itself in a side galley, functioned as a kind of ur-text that contained the added idea of reflection. Patron (White Dress), 2020, based on Friedlander’s New York City, 1971, was flanked and set off by the two paintings of face-down swimmers seen from above, the dark Untitled (Green Swimming) based on a photograph by Dorothea Lange and the lightfilled Untitled (Blue Pool) based on a Kertész, which acted like arrows pointing in opposite directions.

The syntactical arrangement, ripe with potential for reading-in in the context of the art gallery, indicated a closed circulatory system in which the art world and its rituals and the artist’s private and public journey through them were reflected; here is where the allegory lay. ❚

“Vignettes” was exhibited at Catriona_Jeffries, Vancouver, from February 13 to March 27, 2021.

Nancy Tousley, recipient of the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts in 2011, is an art critic, writer and independent curator based in Calgary.