Damian Moppett

Damian Moppett’s work is laced together by a network of relationships that comes into full view in “Collected Works” at the Rennie Collection at Wing Sang in Vancouver. The 42-year-old artist’s relationship to art history, past and recent, the shifting relations among his mediums (painting, sculpture, drawing, photography, ceramics and video), displacement and the kinships he demonstrates between apparent opposites like Modernism and craft, Realism and caricature, autobiography and masquerade, then and now, original and copy, stabile and mobile, balance and falling and art and life—are all here. The slippery double-nature of these relationships is brought to the fore, as well. Moppett’s doubling is both a balancing act and a distancing device, which the artist uses to separate himself from his work and to train our focus on the objects he makes.

This might seem a contradictory claim to make about someone who has produced 140 drawings and watercolours, which he considers a single work (2004–11), that seem to reveal his inspirations, inner thoughts and private life. They do and they don’t, however, and it takes seeing a lot of his work in one place to understand. This is Moppett’s largest exhibition to date. Assembled over a decade by collector Bob Rennie and presented in an elegantly thought-out installation, the 155 works arranged on three floors of the Wing Sang building cover the years 1998 to 2011 in a tightly edited retrospective of Moppett’s work at mid- career. It is remarkable that this has been done by a private collection and in ways that open the door to deeper insights into Moppett’s project. Works not shown together before have been positioned to illuminate each other.

Damian Moppett, 1815/1962, 2003, DVD:NTSC, 15 minutes, 39 seconds; Poster: LightJet print; 2 drawings, graphite on paper. Poster: 61.25 x 49.25”. Drawings: 15.25 x 17.625” and 15.25 x 15.625”. Photograph: the artist. Images courtesy the artist and Rennie Collection, Vancouver.

Six untitled “monster paintings,” 1998, and a yellow stabile with a hanging tray of small clay bowls are shown together in the first gallery, and the juxtaposition is enlightening. It expands on Moppett’s use of caricature. In much the same way that the comically grotesque monsters—paintings of drawings à la Mad magazine’s Basil Wolverton—are caricature dressed up in the tonier guise of portrait painting, the Looney-Tunes stabile is a caricature of a certain kind of 1960s welded-metal sculpture. The monster paintings, seemingly cobbled together from entrails and genitalia, and the mongrel sculpture are each instances of what Mike Kelley, in his 1989 Artforum essay “Foul Perfection: Thoughts on Caricature,” calls “secret cari-cature—an image of low intent masquerading in heroic garb.”

Sacred and profane bound together in Moppett’s work become critique. In relation to notions of high art, caricature and parody are the stones in his slingshot in a David vs. Goliath contest with the conventions of high Modernism, which gives new life to moribund art forms. Judged by the criteria of the Modernist art he lampoons, this is bad art, very bad art indeed. Judged in its own right, Moppett’s work is serio-comic and on target: “a fouled primal form is a caricature of the very notion of perfection,” Kelley writes, “and when we see this…we cannot hold back a shout of glee.” Neither, one imagines, can Moppett, although his ironic strategy succeeds so well partly because he executes it with perfect deadpan.

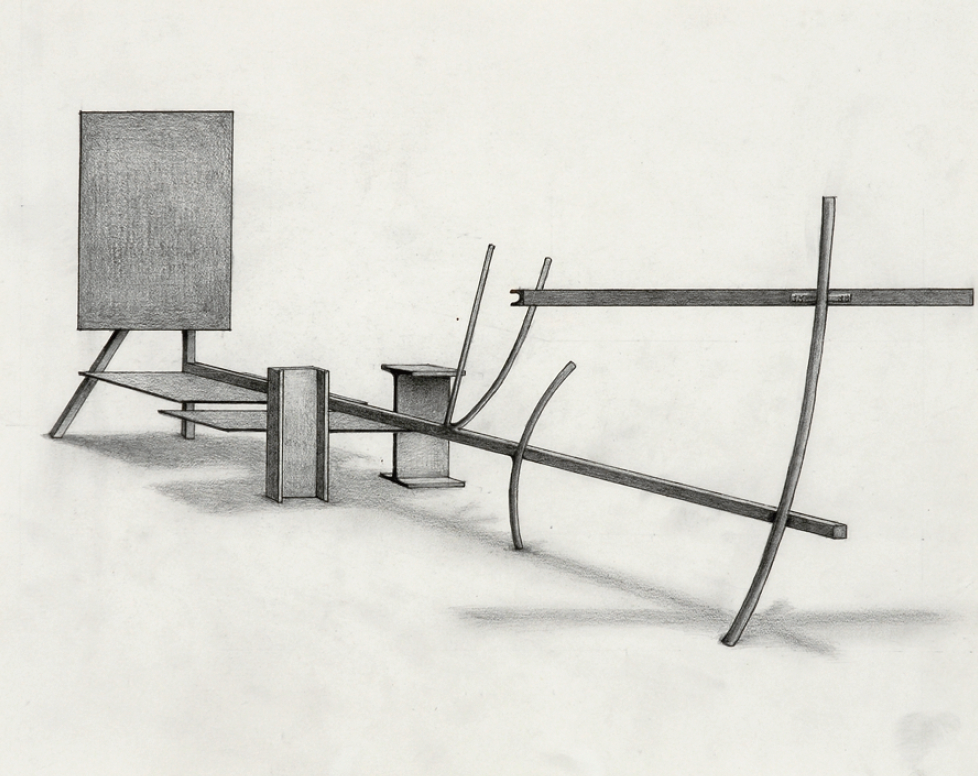

1815/1962, 2003, the 18-minute costume video in which Moppett plays a 19th-century trapper in the woods and two drawings of the compositionally similar models, one for the rustic trap the trapper builds and the other for Sir Anthony Caro’s iconic sculpture Early One Morning, 1962, introduces the idea of a persona and the high art vs. utilitarian craft dichotomy that he proceeds to level. Moppett has pursued these themes in the years since 2003 in such works as the Calderesque stabiles and mobiles, the plaster sculptures after Rodin’s The Fallen Caryatid, 2006, The Acrobat, 2006, the biomorphic abstractions like Figure in Transition, 2007–2008 and the drawings after Rubens, 2002. Thus the basement gallery with the video and drawings, as the artist says, holds the key to what’s above on the Rennie Collection’s top floor.

Damian Moppett, Figure in Transition, 2007–2008, plaster, steel and wood, 45 x 67 x 48”. Photograph: SITE Photography, Vancouver.

Suspended from a soaring, three-story-high ceiling, the show’s newest sculpture, Broken Fall, a colossal mobile composed of Caro-red bars and discs, has dropped an element that lies underneath. Art can be not only comical, it can be dangerous too (Pace Richard Serra). The 25.5-foot-high work’s size and command of space inspires awe, but it is the accident-prone aspect that adds frisson to its physical relationship to viewers, and makes them laugh. Nearby works investigate relationships between sculpture and painting. In Untitled, 2010, it’s as if Moppett has pulled an abstract painting open like an accordion and embodied and extended its components into space to become sculpture, not unlike the horizontal unfolding of Early One Morning, which led to its vaunted vertical sculptural pictorialism.

In Studio at Dawn, 2009, he reprises the composition of Early One Morning in nearly one-to-one scale, but sets the flat, shelf-like elements with glazed stoneware pots and paints the whole structure white. Shown in a white gallery, Studio at Dawn seems almost to disappear, as if flooded with light, making the stoneware the standout feature.

Painting is Moppett’s medium for depicting the studio, shown alternately as a mundane place filled with clutter or a dark, mysterious cave-like space holding works in progress. Among the paintings, Large Red Candle, 2010, a still life in which a burning candle sheds its light on a studio table, could refer to his father, the painter Ron Moppett. In the 1980s, the elder Moppett made some 50 paintings in a variety of styles using this highly symbolic image. He adopted the persona of Vincent van Gogh in his work of 1976–79 and had himself photographed made-up as van Gogh for Self Portrait with a Bandaged Ear, 1978.

Damian Moppett, Broken Fall, 2011, aluminium and steel, 25.5 x.15 x 15’. Photograph: SITE Photography, Vancouver.

The younger Moppett’s drawings and watercolours, which form the core of the exhibition and of this decade’s work, contain references to his mother, the artist Carroll Taylor-Lindoe and to his artist grandfather Luke Lindoe, a family in which everyone’s practice included painting, sculpture and ceramics, simultaneously or at one time or another. The drawings and watercolours also feature two important artistic reference points for Moppett in the filmmaker and photographer Hollis Frampton and the artist Mike Kelley, who are part of his intellectual milieu.

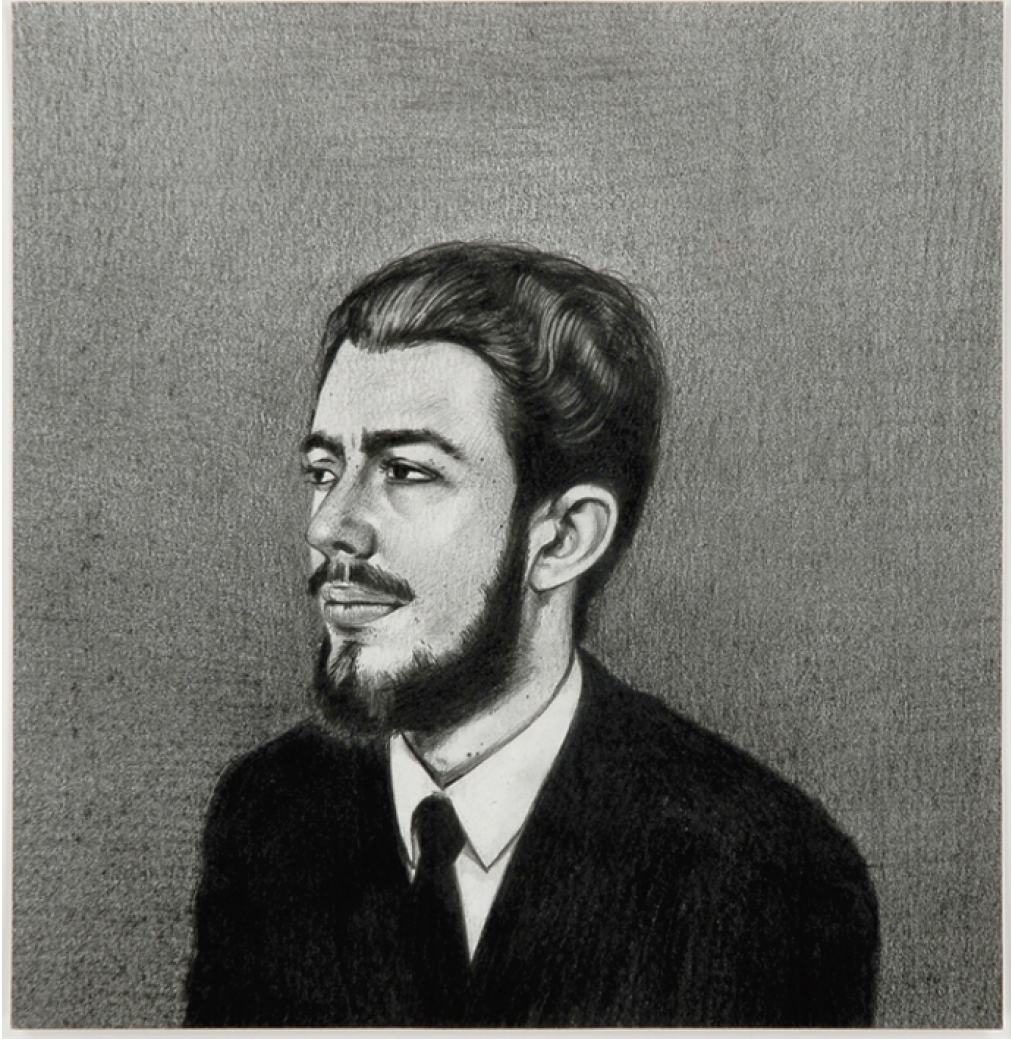

The drawing Artforum with Mike Kelley’s “Foul Perfection: Thoughts on Caricature” signals Kelley’s significance to Moppett’s subversive thinking. The Frampton connection appears in several drawings. Moppett directly adopts Frampton as a persona in Self Portrait as Hollis Frampton, 2004, a drawing of a photograph of himself made up to look like Frampton as he appears in the photograph Self Portrait, 1959. Moppett takes advantage of a physical resemblance, but there is also an intellectual kinship between the two men and, perhaps, a model in Frampton’s practice and writing for achieving the distancing self-awareness that Moppett, who practised photography in the 1990s, seeks in his work.

Frampton’s early photographs and those he burns in the film (nostalgia), 1971, mirror the primary categories of images in Moppett’s drawings and water- colours: fellow artists, artworks, the darkroom or studio, places, his self-portrait, etc. Frampton writes about distancing of the camera, making him “not, as it were, the person hovering behind the artifact but rather behind the thing that made the artifact.” In the essay “Erotic Predicaments for Camera,” 1982, he writes further about a photographer (Les Krims) photographing himself: “the maker of the piece, synonymous with its prime watcher, is watching himself… performing the act of making.”

The sense of a persona at work in Moppett’s post-2003 oeuvre, especially in the sculpture and the drawings and watercolours, takes such strong hold that this observation might be extended to “performing the act of being an artist” (performing a career), as indeed Moppett portrays himself as artist/performer in the headless figure of The Acrobat. Moppett has said he prefers the term “inhabiting” to “quoting.” He is not simply an artist who quotes other artists and artworks in the brilliantly done drawings and watercolours. These works taken as a whole are the construction of the persona “Damian Moppett,” more than of an artist/self or a diaristic archive. They do not have the intimacy of the diary or sketchbook. They are not “based on photographs” so much as they are drawings of photographs, some, like the one of Frampton’s photographic portrait of Carl Andre, rendered subtly in every realistic detail. They are illustrations that accumulate into an illustrated history not unlike that found in art magazines and artist monographs.

Perhaps the supreme irony of the drawings and watercolours, which Moppett completed as a series not long before this exhibition opened, is its parody of the work of art historians and critics for whom his career becomes an archaeological site. He is laying it all out before us as parody but, because his work is so affecting, having his cake and eating it, too. ❚

Damian Moppett, Self Portrait as Hollis Frampton, 2004, graphite on paper, 7 x 7”. Photograph: the artist.

“Damian Moppett: Collected Works” is exhibited at Rennie Collection at Wing Sang, Vancouver, from November 26, 2011 to April 21, 2012.

Nancy Tousley is an art critic, journalist, independent curator and Critic-in-Residence, Alberta College of Art and Design.