“Crack the Sky” - La Biennale de Montréal #5

“Crack the Sky,” the fifth edition of La Biennale de Montréal organized by the Centre international d’art contemporain de Montréal (CIAC), and ably curated by Wayne Baerwaldt, was as interesting for what it included as for what it conspicuously left out. Despite much expectation and hoopla, Baerwaldt, who has something of a reputation for being a curatorial tightrope walker and maverick, and who was recently appointed as director of the Illingworth Kerr Gallery, Alberta College of Art + Design, did not emcee anything like a lollapalooza of a show. But, then, neither was he found sprawling senseless on Saint Antoine Street West after nimbly performing a high-wire act between the grandly eclectic (and ambitiously global) in scope and the often achingly intimate, emotional (and likely to get lost in the shuffle, low key) in tenor.

Despite much discussion of border crossings in the more obvious sense, and the curator’s own persuasive remarks concerning ideas of post-nationalism or boundaries, the real crossing of borders here meant a host of inward journeys, and the borders that were crossed were mostly between the inner psyche and the exterior firepower and suggestiveness of the artworks for each viewer. In any case, as far as Baerwaldt’s curatorial performance goes, the real question begs to be asked: just how commanding a curatorial voice is necessary to hold in check a hectic clamour of artistic voices, which, despite all that laudable talk of national and international “borders,” seldom gelled into a unified or even coherent choir but mostly sprawled across several venues downtown like the eloquent remains of the day?

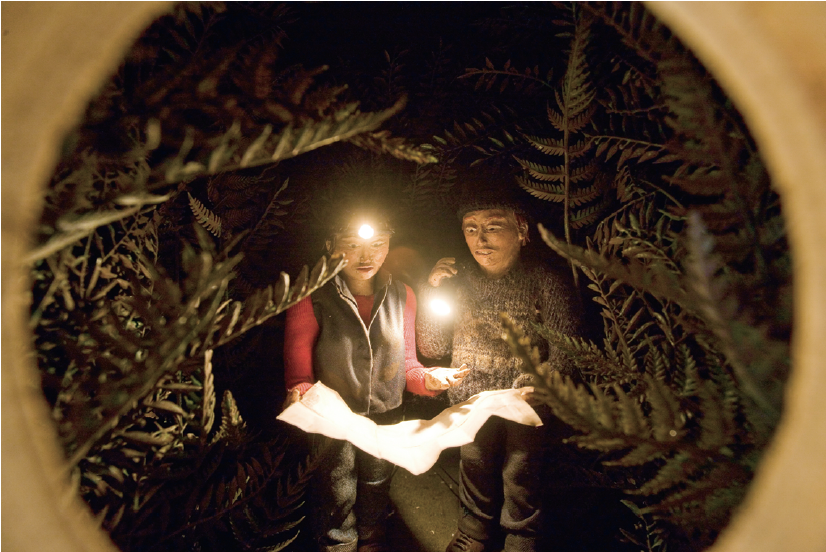

Noam Gonick and Luis Jacob, Wildflowers of Manitoba, 2007, multi-channel video installation, geodesic dome, attendant, turntable, reel-to-reel player, cycle of loops-duration variable. Photo: Guy L’Heureux. All courtesy CIAC/ Centre international d’art contemporain de Montréal.

The exhibition featured a selection of recent works by both emerging and better known artists from around the world, with some 60 artists from Canada and several other countries, including South Africa, Brazil, China, Denmark, Uruguay and the United States.

Grouped in chaotic, non-thematic and sometimes wayward fashion at various venues around town, including the École Bourget and its annexe, the Galerie de l’UQAM, the Galerie Liane and Danny Taran Gallery at the Saidye Bronfman Centre, Parisian Laundry, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and the Cinémathèque québécoise, “Crack the Sky” was envisioned, it seems to me, as the latter-day equivalent of a Ken Kesey bus tour, and hallucinatory it sometimes was. The self-described HQ of La Biennale was in the École Bourget—from its basement to its top tiers, as well as its Annexe next door, right in the heart of downtown Montreal.

First of all, my personal hit of the show, Janice Kerbel. Kerbel’s contribution was a spoken radioplay produced by BBC Radio Three in Britain. It was perhaps the most compelling single piece in the show. To be showered with cascading sequences of those spoken cadences—King James’s biblical, Samuel Beckett-like, Harold Pinterish long soliloquies—was moving, intimate and, above all, very compelling. Kerbel’s literary propensities were as welcome a revelation as her cerebral and spectral map drawings on adjacent walls. They had you from hello, and how often can you say that about an audiotape or conceptual drawing?

Eleanor Bond, Places for Sleeping and Working, 2007, mixed media and oil on primed paper, 50 x 70 cm each. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Other artists ranked high up in my personal hit parade. For instance, Sarah Anne Johnson, from Winnipeg, showed miniature dioramas of lovingly handworked figurines of humans in a nature setting, which were remarkably engaging. Effortlessly drawing us in, they haunted the mind like fugitive ghosts. I sat hunched in a small room, warming to the metaphoric heat of her crackling bonfires like her beer-drinking protagonists themselves, menaced by the night, aware all the while that just beyond the outer ring of darkness, the wolves lay in waiting.

Eleanor Bond, the Winnipeg-born, Montreal-practising painting savant, was a welcome presence in a show with a paucity of painting content. Her work was as radiant as ever. Toronto artist Michael Awad and Calgary’s Evan Penny worked their staggered, specular anamorphic magic like the many-facetted images of a Dutch polyprism or the slides in a magic lantern from another era altogether. Their new collaborative work, a remarkably effective merger of photography and sculpture titled Panagiota: A Conversation, was definitely a home run. Awad, a latter-day Muybridge, took a series of time-lapse photographs of a talking head, which Penny then modelled in sculptural form with mesmerizing results—a 3-D portrait that literally raised the hairs on the nape of my neck.

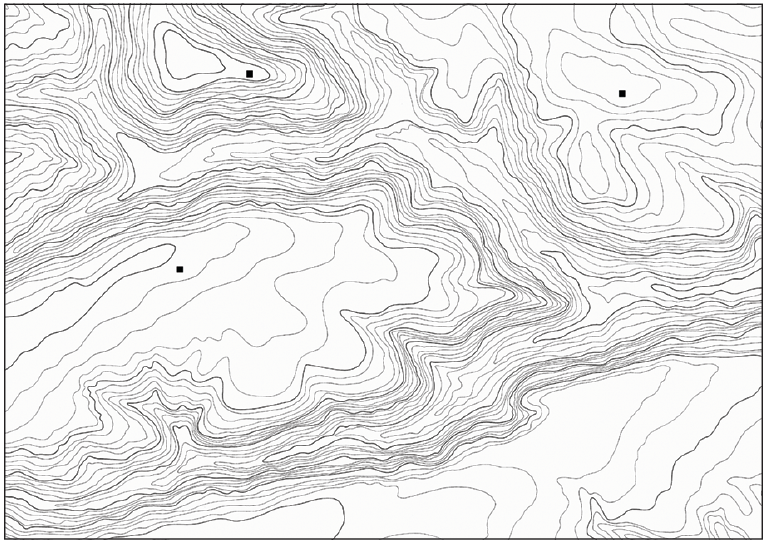

Janice Kerbel, “Town Studies (Three-House Town),” 2005, etching on paper, 42 x 59.4 cm.

Jesper Just, in a David Lynch Silencio mode, care of Federico Fellini’s 8 ½, and employing the most obvious cinematic devices, gave us a consummately exhilarating short film—and the most seductive, mating-ritual whistling routine I’ve ever heard, at once over-the-top kinky and wholesale brilliant in its way. Theo Sims’s The Candahar, a hole-in-the-wall watering hole with real resonance that derived its name from a Belfast street that really existed, beckoned. Sitting at the bar in this Irish pub simulation was like visiting a waiting room and resting place between art hits on the itinerary. Geoffrey Farmer’s Puppet Kit Workshop was an hypnotic portrait of an evolving puppet that resembled more than anything else a Senufo Kafi gueledio fetish figure or Hopi Kachina doll.

Lynne Cohen’s seven large-scale colour photographs were a fitting sequel or coda to her recent—and exemplary—exhibition at Parisian Laundry. These works made it hard to leave the horizontal slot of a room in which they were exhibited (a space as compressed as they were, if less clinical). I might have thought the horizontal slot-like rooms in which many works at the Bourget were exhibited would not work—but they did, surprisingly. Annie Pootoogook from Nunavut, winner of the prestigious Sobey Art Award, and whose work is also on exhibit in Documenta this year, exploded to laudable effect the orthodox imagery of “Inuit Art” in treating with Socratic honesty homespun, rendered images of her own domestic upbringing. The works exhibited by American sculptor Bill Smith also deserve mention for their radiant ingenuity. Scott McFarland’s photographs looked pristine and enticing. And then there was Julie Doucet, legendary Montreal cartoonist/savant, author of extraordinarily frank and admirably off-the-wall graphic novels and, more recently, visual artist. The collaged language poems (from an alphabet hand-cut from newspapers) she showed were evidence of the bright future ahead for her in visual art. Chris Cran, a talented painter from Calgary, exhibited kinetic sculptural pieces that were arresting in themselves—and also in instructing viewers of his endeavours beyond painting. Calgary artist Ryan Sluggett also showed interesting work. His trio of DVDs documented hectic improvisational antics in his studio with tremendous, and telling, abandon.

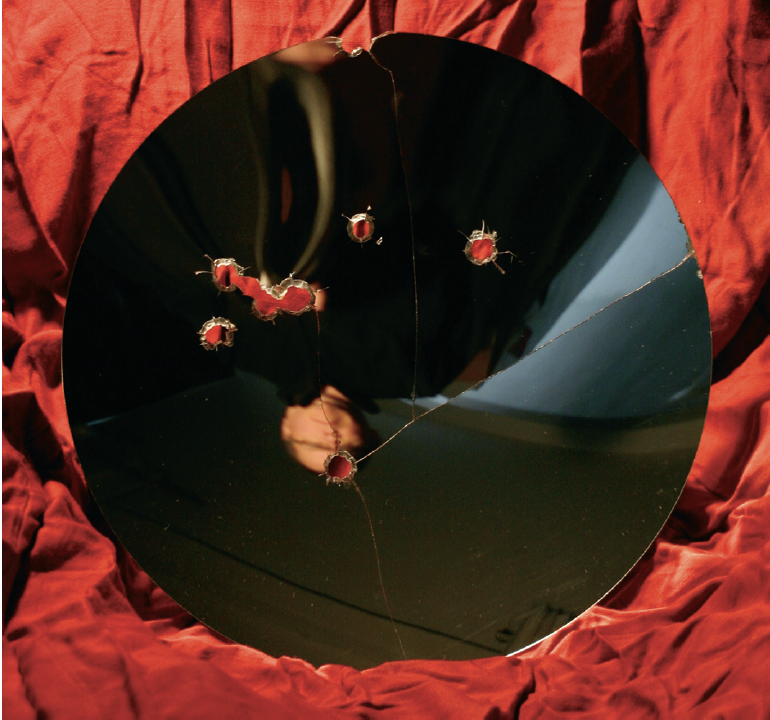

Chris Cran, William S. Burroughs Shot Mirror Project, 2007. Courtesy Chris Cran. Private collection.

Another pick hit of this locale was the work of Calgary artist David Hoffos, whose remarkable recessed-wall miniature projections/installations (the fifth instalment of his Scenes from the House Dream series) I returned to several times with increasing interest and without ever growing jaded. Indeed, Hoffos’s take on suburbia, with its echo of the work of Eric Fischl (however remote)—I mean, its dark, spooky side after sundown—did what all potent art does: summon up a powerful psychological imbroglio for the engaged viewer.

At Parisian Laundry was Brian Jungen’s iconic sculpture built up from a surfeit of golf bags, which read as a serendipitous, if unlikely and magnetic, totem pole. It bespoke a certain level of formal invention followed up nicely by the work of Graeme Patterson from Woodrow, Saskatchewan (population: 10), who showed small-scale buildings, churches and other structures with interior animation. These virtuosic replicas, with their ambulatory inhabitants, were diverting, winsome and a welcome respite. The interior of Parisian Laundry, one of Montreal’s most promising new galleries, was frankly luminous as a result of this welcoming divertissement.

Sarah Anne Johnson, Lost, 2007, mixed media diorama, 33 x 33 x 33 cm. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Also at Parisian Laundry were works by the lionized Montreal collective BGL (Jasmin Bilodeau, Sébastien Giguère and Nicolas Laverdière). Their all-white melting sculpture of Darth Vader’s trademark space helmet (white now rather than black as it was in the Lucas films) pooling onto the floor plane like so much spilt milk from the bottle of invention was definitely another high point of the Biennale. The work of Uruguayan artist Ignacio Iturria was also compelling. I should also single out the pairing of Winnipeg filmmaker Noam Gonick and Toronto’s Luis Jacob in their multimedia installation Wildflowers of Manitoba, a post-hippie, homoerotic performance installation that brought together photographs, projected moving images and the mellifluous sounds of Lake Winnipeg in an all-in-the-round tableaux vivant.

Mention should also be made of Brazilian artist Iran do Espirito Santo’s decidedly minimalist but compelling wall paintings, an in situ installation of white and grey abstracts, at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and aptly titled Déjà Vu, an environmental volume that had a Robert Irwin/Agnes Martin-like resonance. And Sylvie Gilbert brought her arresting and welcome show, “Comic Craze”—more than 400 books by some 100 artists—under the umbrella of the Biennale as well. The work of many outstanding Quebecois comic artists was highlighted therein.

Paulo Whitaker, Untitled, 2006, oil on canvas, 195 x 327 cm. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

At the Galerie de l’UQAM, brilliant resident curator Louise Dery showed the work of David Altmejd. The astounding Altmejd invited us to cross over to the dark side in assimilating his feverishly imagined werewolves and endlessly inviting tomorrow worlds. Altmejd, who represented Canada at the Venice Biennale this year, showed beautifully calibrated, apocalyptic artworks that hooked us from the get-go with their élan—and hallucinatory clarity.

Curator Baerwaldt deserves marks for inclusiveness and madcap eclecticism, and for hitting the proverbial ball right out of the park not once but several times—Kerbel, Hoffos, Sarah Anne Johnson, Bond, Farmer, McFarland, Doucet were worth the price of admission. If “Crack the Sky” transgressed borders more real than imagined, and sometimes more imagined than real, it was the lively—and enlivening— transgressions of some participants that moved me most and the sheer inventiveness of others that stayed with me longest. ■

“Crack the Sky,” the fifth edition of La Biennale de Montréal, ran from May 10 to July 8, 2007.

James D. Campbell is a writer and curator based in Montreal.