Contemporary Iranian Art

This past summer four galleries and museums in New York featured extensive exhibitions of the work of more than 100 Iranian artists living in and outside of Iran. Their openings happened to coincide with the eruption of mass demonstrations in Iran protesting the results of the recent presidential election. The most ambitious of these was the ground-breaking show at the Chelsea Art Museum, “Iran Inside Out.” Its curators, Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath, attempted to escape the traps of cultural stereotyping by extending the parameters of the exhibition.

Made up of 210 works, “Iran Inside Out: Influences of Homeland and Diaspora on the Artistic Language of 56 Contemporary Iranian Artists” filled two floors of the gallery’s enormous space, and encompassed a dizzying variety of paintings, photographs, sculptures as well as film, video and other installations. Thirty-five artists in the show live inside Iran and 21 artists live outside but frequently travel back and forth. The exhibition showcased a wide variety of issues ranging from art and politics, the construction of gender and sexuality, to consumerism, Pop culture and kitsch. In a further effort to tweak cultural stereotypes, it was divided into five thematic sections, with provocative titles such as “In Search of the Axis of Evil,” “From Iran to Queeran and Everything in Between,” and “The Culture Shop: Special Sale on Stereotypes – All Must Go!”

In viewing the exhibition, it became increasingly apparent that the common denominator in the artistic practice of contemporary Iranian artists is their consciousness of the multiple ironies governing representation. The irony found in these works, however, is not the cool detachment of postmodern irony that is often coupled with a cynical skepticism about the efficacy or even the value of action. Where the postmodern subject adopts irony almost as a defensive reflex against feelings of powerlessness, Iranian irony seems a liberating aesthetic and moral strategy. Artists contributing to this exhibition generate irony by juxtaposing opposites such as male/female, Western/Eastern, ancient/modern, sacred/profane. A prevalent strategy is the juxtaposition of written text and visual image, with many artists using written text as a palimpsest to explore how culture constructs the knowing subject.

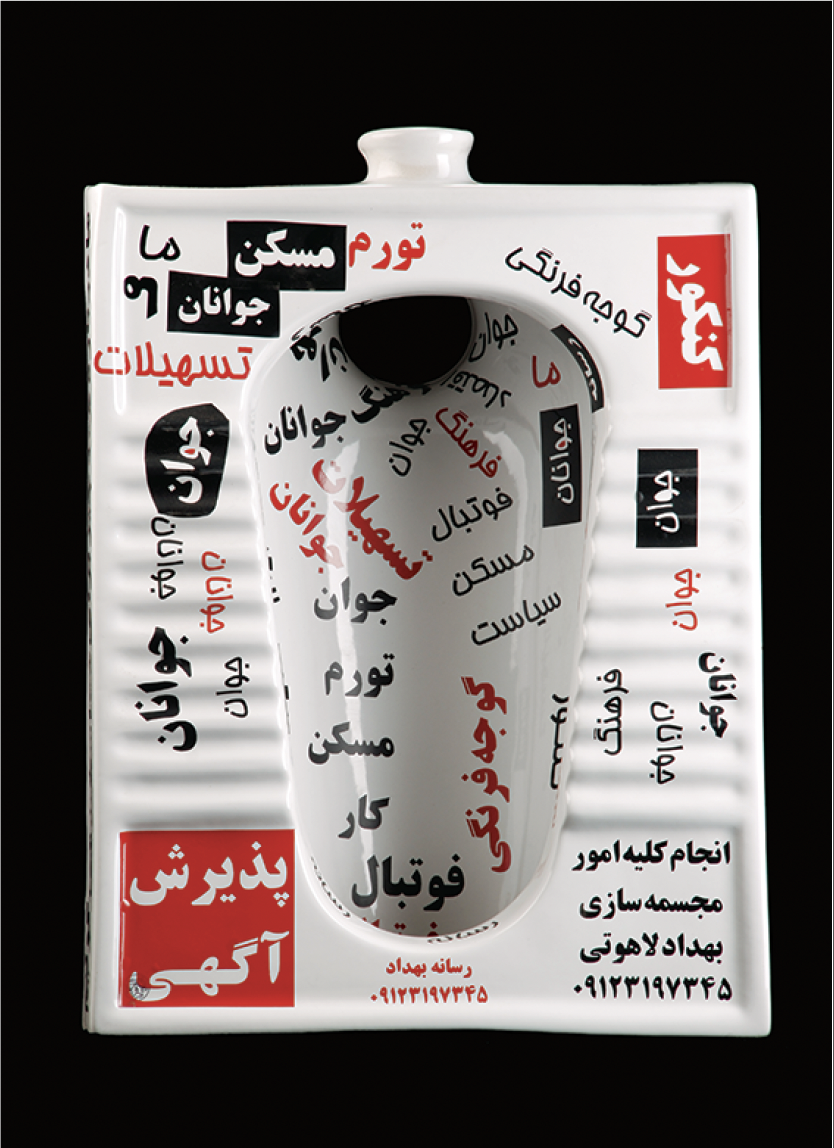

Behdad Lahooti, A Cliché For Mass Media, 2008, ceramic with print over, 57 x 42 x 22 cm. Image © artist, courtesy of Aaran Gallery and Chelsea Art Museum.

In Farideh Lashai’s beautiful video installation Edouard Manet—Le déjeuner sur l’herbe is projected onto a canvas overlaid with Persian calligraphic text. Manet’s image then slowly dissolves into a photograph of three young Iranians in the same pose. In Shirin Neshat’s beautiful photographs, calligraphy encircles a woman’s arm like a sinuous bracelet, drawing attention to the way texts inscribe the female body. Similarly, Sadegh Tirafkan in his “Sacrifice” series shows men wrestling against a backdrop of calligraphy, suggesting that the masculine subject is not only constructed by heroic narratives but must also wrestle with their demands for martyrdom. Irony is also generated when the ironist—the sophisticated, worldly observer—is juxtaposed with a naïve counterpart, unaware of, or oblivious to, the meaning of events swirling around him. Sometimes both points of view are found within the same individual, and the ironist must feign naïveté, as in Hamlet, for social survival. As such, the divided self is part of the situation of irony. Many works in this exhibition show this split within the self and within society through the use of refracted mirrored or doubled images. There are also multiple ironies around the notion of the “naïf.” Is it the censor who is naïve or is it the artist posing as such? Is it American society or is it Iranian society ignorant about the cultural implications of its own past?

Of particular note are works by Farhad Moshiri and Shirin Aliabadi, We Are All Americans. In the witty supermarket series, photographs of everyday artefacts seem to be a celebration of consumer culture, their bright colours reminding us that commodities are a site of pleasure. But the slogan, “We Are All Americans,” subverts the images—revealing that products and product placement smuggle in ideology and change culture. Behdad Lahooti’s A Cliché for Mass Media, in a gesture meant to scandalize authorities, draws on Duchamp’s urinal as sculpture for reference. Under Islamic purification rituals, any urinal, no matter how sparkling and pristine, will always/already be regarded as “unclean,” as “najast.” To add insult to injury, it is “decorated” inside and out with government slogans in Persian script—Education, Youth, Opportunity, Employment—implying that all those promises have gone down the toilet. Thumbing his nose at authorities, Lahooti has included his name and telephone number should anyone want to reach him.

Roya Akhavan’s use of acrylic paint and meticulous delineation of boundaries between elements in Under the Bruised Sky recall the hard-edged techniques of Op Art. But the exuberant profusion of pattern, the brilliant and dazzling juxtaposition of foreground and background, are highly original and all her own. Her technique is best described as “looped and layered,” the phrase used by the Thomas Erben Gallery in New York as the title of its show of her work concurrent with the exhibition at the Chelsea Museum. Looking through the loops and layers of positive and negative space, we see the hidden forms of horses and lances emerge. These forms do double duty—serving not only as an allusion to the prevalent imagery of Persian miniatures, but also as a witty and deliberate reference to Uccello’s use of linear perspective in his painting of The Battle of San Romano (c. 1435–1460). As in Uccello, the lines of spears in Akhavan’s canvas provide a controlled visual background for the chaos of colour and form in the foreground. In between the loops and layers of colour, Akhavan has placed tiny cut-out shapes of human beings. A closer look reveals that the dominant red shapes in the foreground surface turn out to be anatomically correct human hearts, the long looping threads emanating from them, nothing less than the arteries, circulating their pulsing energy over the surface.

Abbas Kowsari, Women Police Series, 2007, photograph. Images © artist, courtesy of Aaran Gallery and Chelsea Art Museum.

Abbas Kowsari’s photographs in the “Women Police Academy” series capture some of the absurdities of gender politics in the Islamic Republic. The female cadets dress in male police uniforms that are completely cloaked by long black chadors. One photograph, though, captures the paradoxical beauty of this aspect of contemporary Iranian culture. The cadets lined up for inspection are photographed so that we do not see their faces but only their feet, their polished shoes, the perfect crease in their trousers. Only then do we notice their reflections in the wet pavement and realize these cadets are women. The reflected image mirrors multiple ironies: these women have exchanged traditional femininity for a small measure of male power, yet what’s captured in the water is their youth and beauty. The muted colours—greys, browns and blacks—seem to suggest that things are not quite so black and white.

Shirin Neshat’s black and white film Turbulent, 1998, which won the Golden Lion Award at the Venice Biennial in 1999, creates a tense drama around gender roles and the paradoxes of representation. A male singer enters an auditorium to applause by an all-male audience. He turns to the camera and begins to sing a love poem by Rumi. It is a static performance, but compelling in its passion and intensity. Meanwhile, on the opposite screen, a woman cloaked in a black chador stands silently, her back to the camera and to the viewer. She faces an empty auditorium. As a woman, she occupies the position of the marginalised, the voiceless, the unheard. When the man finishes singing, he turns once again to face his audience and receive their applause. But a faint sound catches his attention, he turns. The woman is crooning a wordless aria made up of sighs of longing and low moans of mounting ecstasy. The camera whirls around her as she loses herself in her performance. Suddenly, notions of cultural privilege and authority are turned upside down. The woman who had seemed powerless now embodies power. The haunting sounds emanating from her pre-date human language; they are the source of the emotional intensity that Rumi and, by extension, all poets have sought to represent. But Neshat does not leave the situation at a simple gender reversal. The woman is shown not so much finishing a performance as emerging from a trance, uncertain of what had possessed her. Rumi, as a Sufi mystic, would say the artist had been gripped by divine “in-spiration.” Others would say the source of artistic inspiration remains an eternal mystery.

Ostensibly, Ramin Haerizadeh’s work in “Theatre Group” appear to be portraits, representational art in the 19th-century Qajar style, with vibrant surfaces and familiar objects—a bowl of fruit, paisley fabrics and laces. However, the title “Theatre Group” is a deceptive alibi for the censors. In fact, Haerizadeh—himself gay—has privately dubbed this series “Closet Queens.” On the surface, the apparent subject, a bearded man sitting cross legged, is supposedly an actor of the Qajar period, a kind of dwarf court jester garishly bedaubed to play the female role in the Shi’ite Passion play, the Ta’ziyeh, in which the roles of the women are played by men. To ensure audiences are not taken in by theatrical illusion, a Brechtian-style convention calls for a fully bearded man to play the bride. But what seems to be an exotic and eroticised male body from a decadent historical time is in fact an ingenious pastiche made possible by modern technology. Haerizadeh has used a variety of digitalized images of his own face, elbows and arms to subvert photographic realism, so what appears to be a full frontal portrait is in fact the splicing and conjoining of his own twinned profiles, which seem to be kissing. At the same time, the seeming immodesty of the seated figure is another pastiche, a digitalized manipulation of an innocuous elbow. Through these strategies Haerizadeh simultaneously veils and unveils, constructs and deconstructs, the taboos governing ideas of the body, of masculinity and femininity.

Ramin Haerizadeh, Theatre Group(03), 2008, c-print, 100 x 70 cm. Courtesy Chelsea Art Museum.

Sara Rahbar, born in Iran but living in the United States, uses the image of the flag as a way of representing as well as resolving divided loyalties. Her elegant painting of the American flag is a nod to the work of Jasper Johns. However, she uses the flag’s white stripes as “open territory” into which she can insert/assert in Farsi “Did you see what love did to us once again?” The faint trace of the outline of Iran in the centre of the flag, as well as the repetition of the inscription, create ambiguity as to whose love it was that “did” something “to us.” The flag as sub-text implies “we the people” but remains ambiguous as to who “we” are. Are both nations guilty of loving democracy not wisely but too well? The United States is the older democracy but the younger nation. Iran is the older nation that, too, has loved democracy and reached for it time and again. The inscription is not the vicitm’s—“See what happened to us”—but rather, “see what love did,” implying moral agency on both sides but eschewing blame. The superb equipoise between these heterogenous elements points to the possibility that love may yet find a way to reconcile seemingly irreconcilable differences. In Rahbar’s meticulous creation of the flag, one also senses the artist’s gesture of restoring the American flag burned in the hostage crisis.

Inside and outside Iran, these artists, each in a different way, are confronting what it means to be a subject. Faced with the blank page, the artist living under a repressive regime must answer the key question: how should I use my freedom? Whatever the laws might be inside Iran, whatever the thought police might wish to impose, Iranian artists have broken what Blake called “mind-forg’d manacles.” They have decided to act as if they are always/already free, that they need not repress their creative energies and that their work and artistic practice has value in both the realms of aesthetics and ethics.

The title of the exhibition—“Iran Inside Out”—may just as easily be inverted to become “The West Inside Out” as the artists working in Iran mirror Western practices and, in the process, subvert and invert Western images and mythologies. What emerges is an exuberant celebration of artistic freedom—no matter what the geography. ❚

“Iran Inside Out: Influences of Homeland and Diaspora on the Artistic Language of 56 Contemporary Iranian Artists,” curated by Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath, was exhibited at the Chelsea Art Museum in New York from June 26 to September 5, 2009. Con-current with the exhibition at the Chelsea: “Selseleh/Zelzeleh: Movers & Shakers in Contemporary Iranian Art,” Leila Taghinia-Milani Heller Gallery (ltmh), New York; “Looped and Layered: A Selection of Contemporary Art from Tehran,” Thomas Erben Gallery, New York; “Tarjama/Translation,” Queens Museum of Art, New York.

Dr. Moti Shojania, a writer, reviewer and cultural commentator, teaches at the University of Manitoba. Currently, she is the Chair of the Winnipeg Arts Council.