“Compass in Hand: Selections from the Judith Rothschild Foundation Contemporary Drawings Collection”

It comes as no surprise that “Compass in Hand: Drawings from the Judith Rothschild Foundation Contemporary Drawings Collection” is a panoramic overview, as Christian Rattemeyer, co-curator of the exhibition, attests in his catalogue essay. (Connie Butler, MOMA’s chief curator, is his co-curator.) The collection from which the show is drawn was donated to the museum in 2005 by the eponymous foundation with the caveat that MOMA had to accept the entire trove, as opposed to picking and choosing favorites. Whittling the 2,500 drawings—all of them executed between 1930 and 2005 by more than 650 emerging and established artists—became the curators’ main task, as if they were Henry Higginses extracting an Eliza Doolittle out of the flat files. A wonder of an exhibition has emerged, graceful in its connections, canonical enough in its inclusions, but savvy, too, in its revisionisms. Granted, the palette wasn’t too shabby to begin with. The drawings were amassed at an astounding rate—some say too quickly—by Harvey S Shipley Miller, the Judith Rothschild Foundation’s only trustee, with the help of then-moma curator Gary Garrels. The buying spree took place at a crucial moment earlier this decade when drawing experienced a resurgence.

Alighiero e Boetti, Aerei (Airplane), 1983, ballpoint pen on three sheets of printed paper on paper on canvas, 9 1/8 x 19 1/4”. The Museum of Modern Art. The Judith Rothschild Foundation Contemporary Drawings Collection Gift. © 2009, Estate of Alighiero e Boetti.

The exhibition begins with the basic premise that though the idea or definition of drawing may be simple—pencil-on-paper or a means toward an end—it is, rather, feral and lawless. The first gallery alone exemplifies this thesis, presenting Jasper Johns’s From Juan Gris, 2000, made with ink on transparentized paper; a body print by David Hammons; burned paper compositions by Miroslaw Balka; and a Roy Lichtenstein cut-and-paste still life, Untitled (Table with Two Vases of Flowers), 1997, made with pressure-sensitive tape and pencil on paperboard. The rest of the large exhibition—354 works by 177 artists in total—focuses on stylistic reverberations, subject obsessions and shared sensibilities. It often follows, but sometimes confounds, generations and geography.

Beyond the sheer size and reach of the exhibition, the breadth of the original collection is alluded to by the bounty of three salon-style walls that anchor the beginning, middle and end of the survey. The first, installed in the second gallery, celebrates Minimalism and its influences with the careful interweaving of drawings by Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Carl Andre, Barry Le Va and Vija Celmins, among others. A suite of stately Sandback drawings hangs not far away, as does an Ellsworth Kelly colour-grid study, hung high. A beautiful Blinky Palermo, Blaues Dreieck, 1969/2009, a deep blue gouache triangle, is an all-seeing eye painted onto the wall above an adjacent doorway. The other salon-style walls are more playful, with Rachel Harrison, Richard Hawkins, Franz West, Jack Pierson, and others punctuating one; and figurative works by Luc Tuymans, John Currin, R Crumb, Kai Althoff, Francis Alÿs, Joseph Beuys, Maurizio Cattelan, Lee Lozano and more on the other.

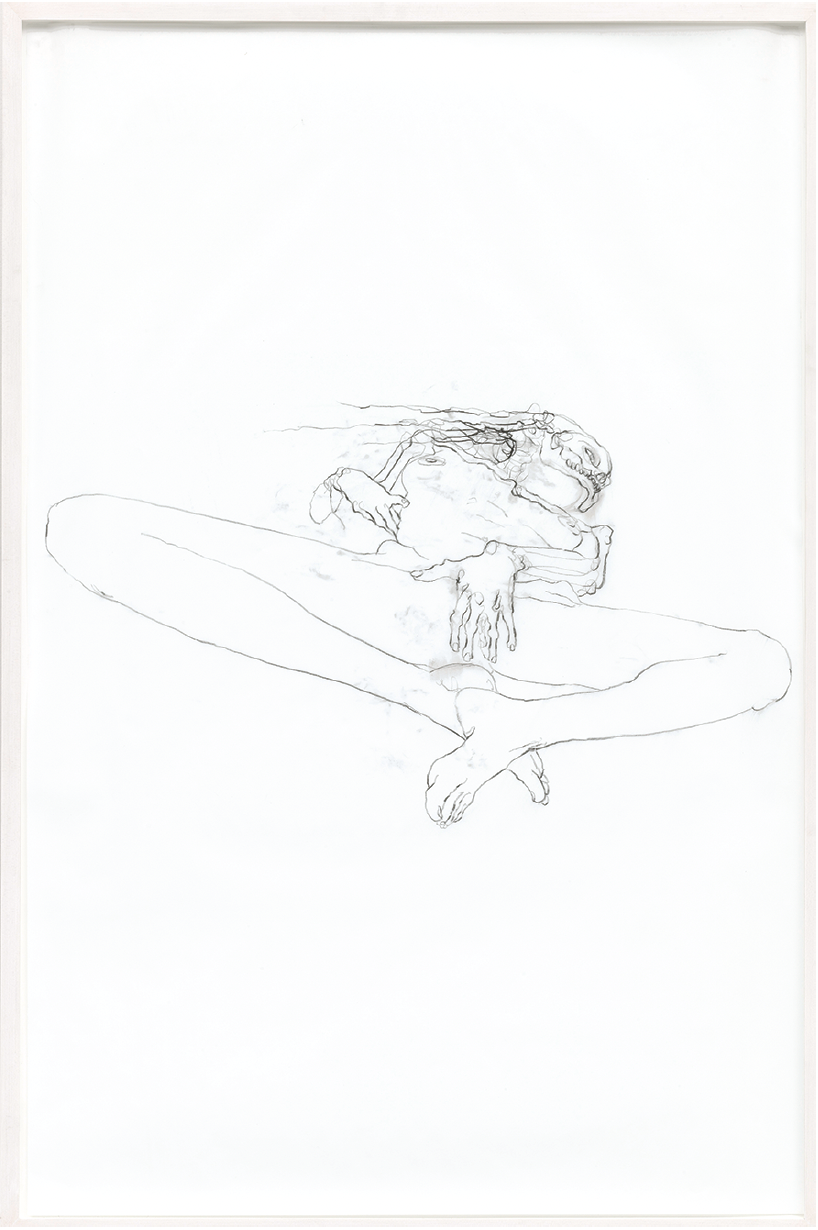

Chloe Piene, Thirty Years Old, 2002, charcoal on transparentized paper, 46 x 30”. The Museum of Modern Art. The Judith Rothschild Foundation Contemporary Drawings Collection Gift. © 2009, Chloe Piene.

The installation features more and less overt connections among the drawings. One gallery comprises an almost lyrical meditation on mapping, with works by Mark Lombardi, Franz Ackermann, Roni Horn, Ján Mancuska, Mona Hatoum, William Kentridge, Richard Wright and Martin Creed. Lombardi’s networking map World Finance Corporation, Miami (c. 1970–79) (4th Version), 1997, counters Mona Hatoum’s Routes II, 2002, ink-and-gouache depictions of flight paths; Horn’s pigment, varnish and pencil works on cut-and-pasted cardstock reveal the maps of their own making, with fingerprints attesting to the importance of place here and in her work more generally. Work No. 341, 2004, by Martin Creed is in felt-tip pen and ink on seven pieces of paper, each one a solid, near-fluorescent colour. One could argue that these sheets map the British artist’s nouveau Duchampian tendencies or, perhaps more simply, a map of the limitations of a modern pre-fab colour palette.

A less clear connection involves a beautiful drawing by Jim Hodges, Happy III, 2001, in which coloured pencil lines carefully extend outward from a centre-point across two pinned-up pieces of paper. This is next to two untitled crumpled drawings—as if they had been discarded and then saved—by Robert Gober. All three possess sculptural qualities. A suite featuring the straightforward pairing of Eva Hesse and Hannah Wilke is complicated by the inclusion of a work by Bruce Nauman, though all the works contain bodies, whether sick, sexualized or abstracted. Gallery after gallery suggest further connections: Gina Pane/On Kawara; Martin Kippenberger/Cady Noland; Nate Lowman/Eva Rothschild. Of course, the collection has its dark underbelly, too, where making connections among works isn’t worth the effort. The more-than-300-page catalogue raisonné of the collection attests to some less desirable drawings by well-known artists and one-hit wonders alike, casualties natural to a gathering of this frenzied magnitude.

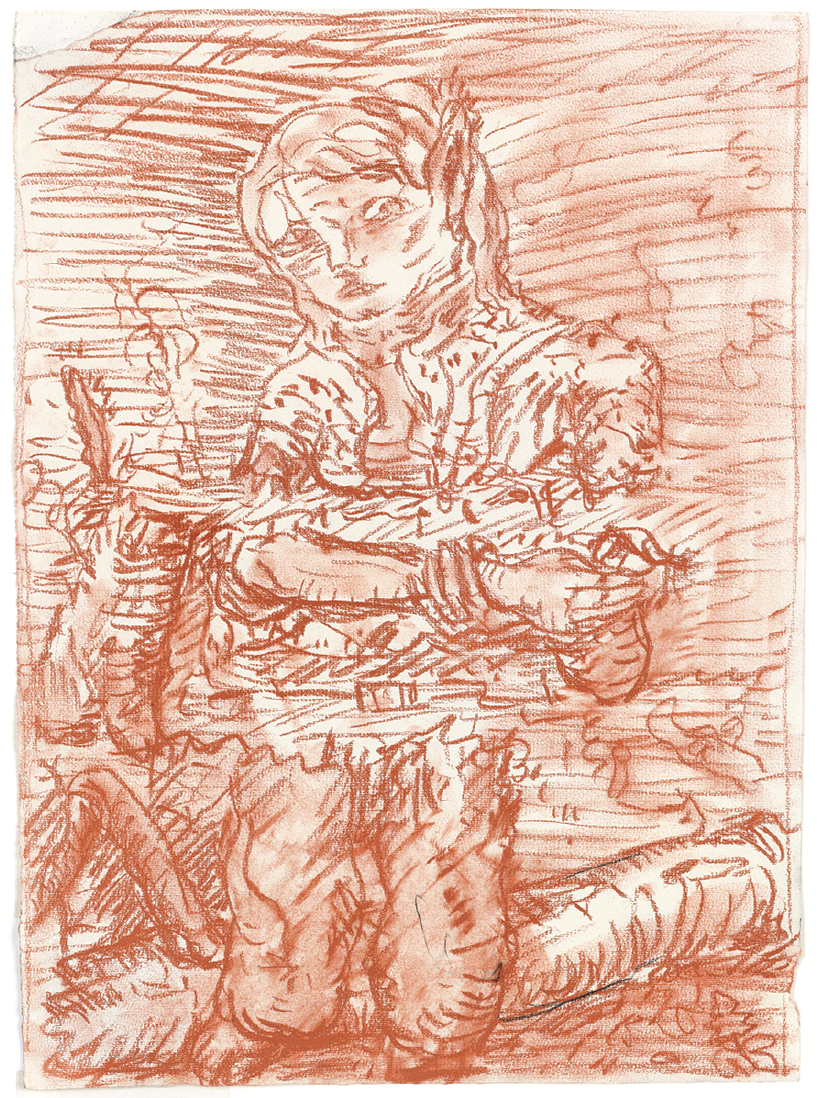

Georg Baselitz, Waldarbeiter (Forest Worker), 1966, chalk and pencil on paper, 17 1/2 x 12 5/8”. The Musuem of Modern Art. The Judith Rothschild Foundation Contemporary Drawings Collection Gift. Given in honour of Gary Garrels. © 2009, Georg Baselitz.

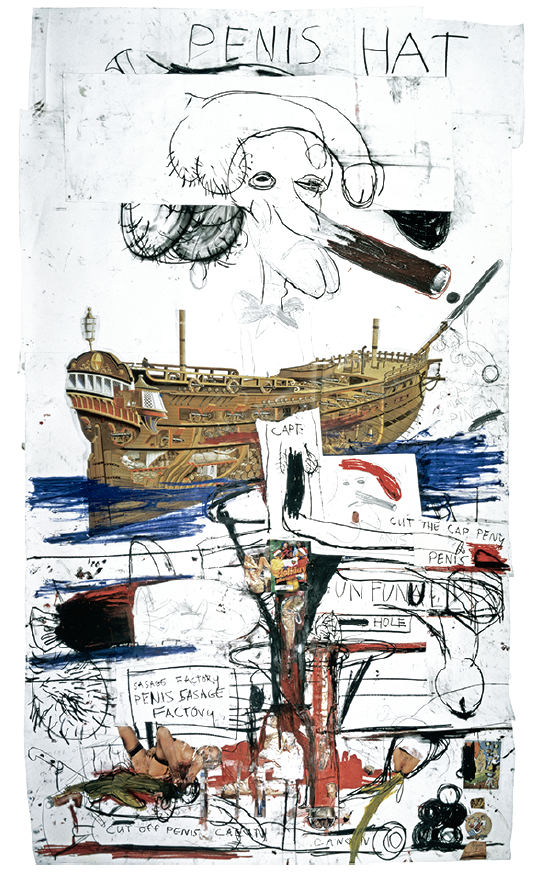

Nonetheless, there is a palpable playfulness in the galleries, which may in part be due to the sense of freedom inherent in the medium itself. This is most apparent in Paul McCarthy’s Penis Ha_t, 2001, a clearly crowd-pleasing, nearly 15-foot-high pirate drawn in pastel across roughly cut and pasted paper, or in Jim Lambie’s corner-spanning composition in black tape and cutouts of colourful eyes. Kelley Walker’s _nine disasters, 2002, too, presses the medium into exuberant territory; coloured wallpaper masks an entire wall and is then hung with even more of his work.

Criticisms of this exhibition are those typically lobbed at most of the Modern’s endeavours, which have to do with its indecisiveness about whether to guard the canon or champion the new. “Compass in Hand” plays both roles and not, as some have claimed, to the detriment of either. While true that the majority of the show’s works are by established artists and some of Miller’s individual fancies won’t stand the test of time, there remains promise in the more than 2,000 works that have not yet found their way to the museum walls. One hopes that future installments of the collection will be as playful and as celebratory of the medium that knows no bounds. ❚

Paul McCarthy, Penis Hat, 2001, Cut-and-pasted printed paper, charcoal, pencil, and oil pastel on cut-and-pasted paper, 13’ 11 3/8” x 8’ 4”. The Museum of Modern Art. The Judith Rothschild Foundation Contemporary Drawings Gift. © 2009, Paul McCarthy.

“Compass in Hand: Selections from the Judith Rothschild Foundation Contemporary Drawings Collection,” curated by Christian Rattemeyer, was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York from April 22, 2009, to January 4, 2010.

Julia Dault is a New York-based artist and writer.