Clifford Wiens

Architect Clifford Wiens was born on a Saskatchewan grain farm and came to adulthood during the Depression, grounded in the values of hard work, self-reliance and thrift. What kind of architect grows from these founding influences?

There’s nothing like digging postholes and repairing outbuildings to develop a deep-down knowledge of construction, or wrassling with recalcitrant farm machinery to foster a can-do attitude. Add in a five-year program at the Rhode Island School of Design, starting in the seminal postwar years when European emigrés were influencing North American schools, and a return home to set up practice in Regina in the 1950s, and you get a master of Prairie Modernism.

Curator and architectural critic Trevor Boddy uses photos, blueprints, sketches, models (some constructed for this exhibition, “Telling Details”) and video walkthroughs of building sites to pull together a comprehensive, compelling sense of the 79-year-old architect’s practice. Wiens’s work, Boddy suggests, is both pragmatic and romantic, combining ingenuity and practicality with a poetic sense of land and light.

Clifford Wiens, Interprovincial Steel Corporation (IPSCO), Regina, 1960. Photograph: West Studios, Regina. Courtesy Clifford Wiens and Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon.

Certainly, the old myth that Modernism was a ruthlessly imposed international style, scornful of local conditions, cannot stand against Wiens’s buildings, with their thoughtful, specific sense of place. Just take the black and white archival photograph of his Trans- Canada Highway campground, 1964, near Maple Creek. Concrete gives the long, low, ground-hugging building a stark solidity, but the image is actually dominated by a dramatic prairie sky that fills a good three-quarters of the picture plane. It’s a succinct statement of the relationship between the structure and its vast, horizontal landscape.

The Silton Summer Chapel, 1969, is another work that fits into the Saskatchewan landscape in a way that feels both primordial and modern. (“His buildings seem to stand eternal,” writes Boddy in his curatorial comment.) The work’s clearest spiritual expression is pantheistic. Open to the natural setting of the Qu’Appelle Valley, the chapel is wary of standard religious iconography. Its one cruciform shape is formed by the crossing steel braces at the centre of the pyramidical roof, just one of the “telling details” to which Boddy refers in the exhibition’s title. With elemental materials and shapes—a boulder for an altar, a chain-link line channelling rainwater into a cast concrete baptismal font—this is a sublimely simple expression of God in nature.

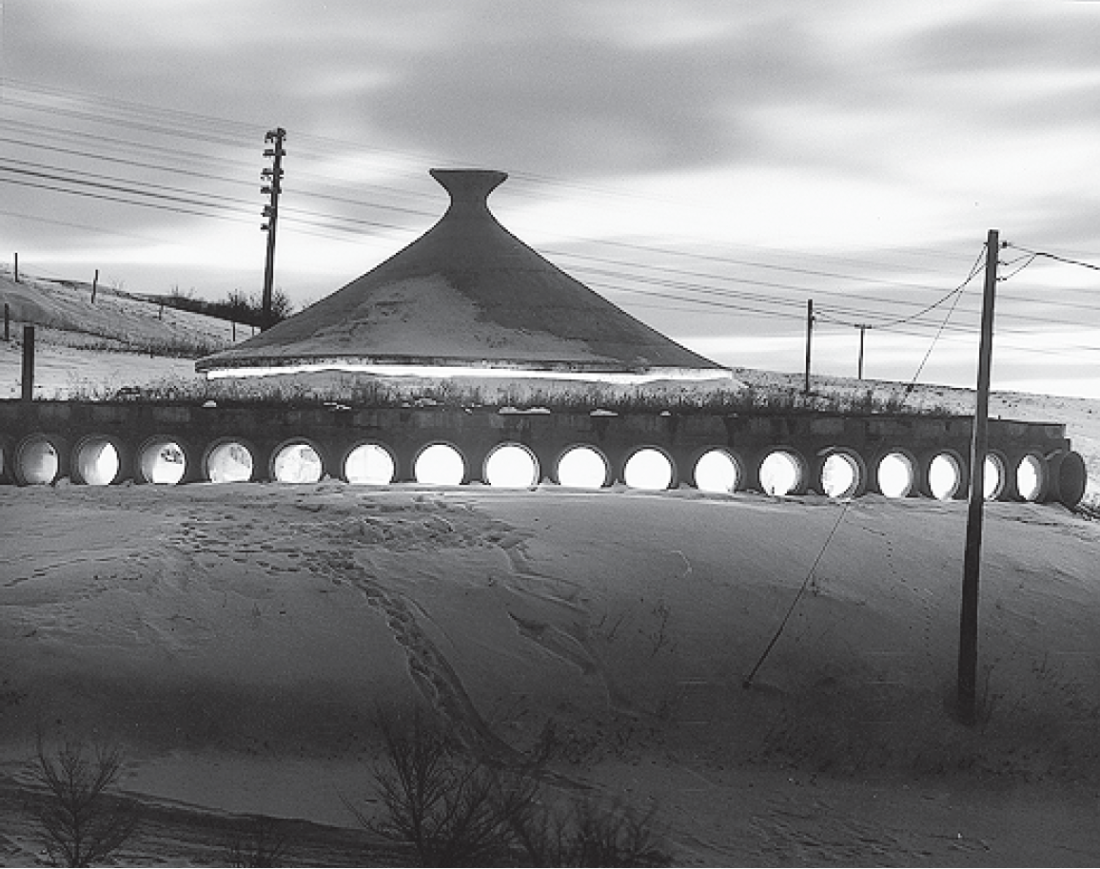

Clifford Wiens, John Nugent Studio (St. Mark’s Shop), Lunsden, 1961. Photograph: Henry Kalen. Courtesy Clifford Wiens.

The John Nugent sculpture studio in Lumsden, 1961, is a circular structure built right into a hillside, with a living roof planted along its flat section. Wiens references the teepee forms of Aboriginal culture—something he did several times in his career—and, within this context, the studio feels ancient and organic. On the other hand, night shots that catch the light streaming out of the circular windows—made of sectioned concrete culverts—call up an eerie, futuristic resemblance to a grounded UFO. One of Wiens’s perfectly realized paradoxes, the Nugent studio is the first Modernist structure declared a Provincial Heritage Property for the province of Saskatchewan. Its inclusion reminds us of how urgent the issue of physical preservation of Modernist buildings has become, just as Boddy’s show demonstrates the need to document, archive and recognize this historical period.

In 1968, Wiens designed a heating and cooling plant for the University of Saskatchewan at Regina. There’s something a bit audacious about taking the structure’s utilitarian purpose and giving it such an expressive form. With its reaching roofline, the plant resembles a temple of concrete, glass and steel, as if technology were a rather severe new religion that demanded our worship.

Clifford Wiens, Trans-Canada Highway Campground Maple Creek, 1964. Photograph: John Fulker. Courtesy John Fulker.

For contrast, look at the prairie-boy modesty of Wiens’s Albert Street office in Regina, 1970. Situated smack between two stubby, unprepossessing buildings, it chooses not to dominate them physically. In fact, the roof’s convex curve actually pulls the building down a little. Wiens cleverly holds our attention in other ways, including some dramatic red flourishes in the interior.

There aren’t necessarily predictable visual similarities from building to building in Wiens’s career, but there is an underlying consistency. Even in an exhibition that spans three decades and ranges through many functions and forms, Boddy still catches something crucial and characteristic in Wiens’s work and life, a tough-minded specificity that grounds his Modernism in the prairies, while giving it a resonance that goes far beyond. ■

“Telling Details: The Architecture of Clifford Wiens,” organized and circulated by the Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon, was exhibited at Plug In ICA from March 2 to April 28, 2007. It will then travel to the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina for exhibition from May 25 to August 26, 2007. It was previously exhibited at Cambridge Galleries in Ontario from August 29 to November 5, 2006.

Alison Gillmor reviews movies for the Winnipeg Free Press and writes about visual arts for the CBC Arts & Entertainment Web site.